China's Early Warring States

A History of Mankind (117)

Welcome! I'm David Roman and this is my History of Mankind newsletter. If you've received it, then you either subscribed or someone kind and decent forwarded it to you.

If you fit into the latter camp and want to subscribe, then you can click on this little button below:

To check all previous newsletters in the History of Mankind, which is pretty long, you can click here.

An utilitarian, or perhaps what in the West would have been called “realistic,” approach to governance became in vogue across China during the Fifth Century BC. This was the time when the old Zhou regional warlords – given to continued quarrels and rapprochements under a shared acceptance of the symbolic supremacy of the Zhou emperor they all claimed to protect – evolved into kings that gave up any pretense of working for a common goal.

The process had started as early as the Seventh Century BC, when the rulers of Qin, the region along the Wei River that had been the old core Zhou territory, first made inscriptions in which they claimed kingly rank for themselves. Wu Gong (r. 697-678 BC) used the royal formula “I, the little child” (of Heaven) to refer to himself and announced that his ancestors had obtained the Mandate of Heaven to govern not just Qin, but the Four Quarters of China, and the surrounding barbarians.

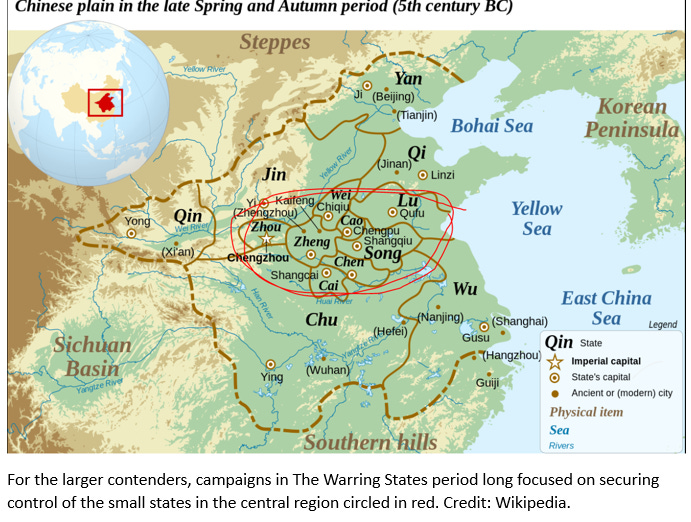

Similar formulations appeared in Qin and, in various shapes, elsewhere during the following centuries, but only became commonplace much later, when Yue on the Pacific coast briefly became one of the main five Warring States, together with Chu on the middle Yangtze River, Qin, Jin – on the Yellow River’s middle course – and Qi, to the east of Jin.

All of these states benefited from sharing borders with a number of smaller, landlocked states that eventually came under their control – as well as ever-expanding, outer borderlands with barbarian peoples, where they could gain land and taxable population that they brought civilization to. In the Zuo Zhuan, a Fourth Century BC history of this period, a specific group of northern barbarian tribes called “Di” are described as “four evils,” and thus ripe for forced Sinicization:

“Those whose ears cannot hear the harmony of the five sounds are deaf; those whose eyes cannot distinguish among the five colors are blind; those whose minds do not conform to the standards of virtue and righteousness are perverse; those whose mouths do not speak words of loyalty and faith are foolish chatterers.”

A rare, intermediate case of Warring State is that of Zhongshan, located to the west of modern Beijing, which appears to have been an ethnically barbarian polity that adopted Chinese cultural practices, fortified cities and farming, so that it gradually fell into the Chinese sphere; it may well be that Zhongshan, rather than one of the Zhou Dynasty states, was the first to build portions of the later Great Wall, to protect itself from other nomadic barbarians from the north[1].

FROM THE ARCHIVES:

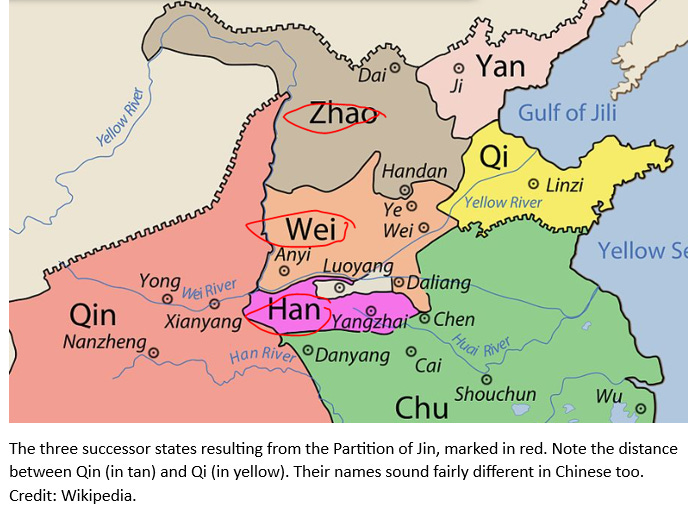

In any case, Zhongshan was briefly occupied by the state of Wei during the early 4th century BC, before it regained an independence that wasn’t always appreciated by other Chinese rulers, as they constantly stressed Zhongshan’s inadequate barbarian background; it finally was conquered by the state of Zhao in 295 BC.

Qin, located on the borderlands connecting with the Hexi Corridor (also called Gansu Corridor) towards the Indo-European-dominated Dzhungaria, and in direct contact with multiple nomads and other dangerous barbarians, soon developed a reputation for warlike politics and ruthlessness, so that propaganda in other states often depicted Qin rulers’ fondness for human sacrifice[2]. For many, Qin wasn’t quite civilized, and thus occupied a strategic similar to that of Macedon for the Greeks: accepted as part of the political game, but mistrusted as partly foreign and unpredictable.

Qin benefited from this reputation, and from a geographic location that trained its armies on all sorts of combat, and allowed for influence from distant regions of Eurasia to trickle down – for example, Qin tombs of the Warring States period often present “flexed burials” with bodies lying on the side with the knees drawn towards the body, common in the steppe but uncommon elsewhere in China.

Nomad incursions and a relative scarcity of farmland slowed down Qin’s ascent, and during the Fifth Century BC other states were dominant in northern China.

Duke Jing (r. 547-490 BC), who became ruler of the distant, hostile state of Qi in eastern China after a powerful minister slayed his predecessor because the predecessor slept with the minister’s wife[3], enjoyed a long and mostly tranquil reign. During this period, his state again became dominant, while remaining wealthy – to the extent that his tomb contained the carcasses of at least 600 horses immolated and aligned in double rows, in an extraordinary feat of conspicuous consumption.

Linzi, Qi’s capital, grew to such an extent that it may have been the only Chinese city to rival the likes of Carthage, Acragas, Syracuse, Athens, Susa and Babylon in size. Isolated from foreign invasions and trouble, Linzi gained fame as a place for Sybaris-style good living, with multiple leisure options including cockfights and street music, as well as games of chance. It also became a center of commerce and culture, just as Jin – with Qin, one of the two other main northern states – plunged into decades of civil war that would end up with its partition between the three dominant aristocratic clans in 423 BC.

This splendid isolation lasted little. Political instability, partly imported from the nearby state of Lu, did affect Qi after the death of Duke Jing and a series of coups and massacres that ended up with the state under the nominal control of some of his descendants. Actual control rested with the powerful, populist Tian clan – which, supported by a large network of lower-class clients, would formally take power as rulers of Qi only in 386 BC.

This situation appeared to create an opening for other states, but they had their own issues to contend with. From 441 BC, Qin embarked on a series of ambitious campaigns, that would last until 311 BC, to take control of the Sichuan plateau, a grain-basket under the control of Tibetan-speaking barbarians.

This left the most bellicose of all Zhou successor states essentially out of the game of thrones for over a century. But even Qin wasn’t immune to internal instability – throughout the Fifth Century BC, a series of weak rulers was controlled by ministers who ensured they would never grow old; their methods were creative and multiple, to the point that, in 425 BC, Duke Huai was forced to commit suicide by the ministers.

Chu, meanwhile, had a decent claim to being the most powerful of all Chinese states, but its sheer size, lack of communications and multiplicity of ethnic enclaves meant that it spent much of its available manpower in civil wars. These problems were only exacerbated whenever successful generals did conquer smaller rival states on the border, adding to the decentralization and scale issues; in 341 BC, Chu conquered Yue and gained control of the lower Yangzi and theoretical sovereignty over southern China, but a lower population density and poor governance meant it couldn’t really project much power.

In the end, the Warring States warred as much within themselves as with other states, a process that created a Darwinian race towards resource optimization: those which became more efficient and able to use resources to build up stronger centralized governments and militaries survived, while the weaker and less resourceful perished.

That’s how budgeting oversight became popular, through the use of budget projections written on a single roll of silk that was torn in half. Local officials kept one and rulers the other, so they could later compare projections each year when officials marched to court to present their estimates. Population registries also became widespread, as record-keeping improved across the board. The Chinese became adept at fighting with numbers as much as with weapons.

[1] The neighboring Chinese state of Yan also has a good claim to having built the first portions of the wall, or at least contemporary walls, as it expanded north and northeast around this era. Those walls looked to protect its settlements in the Liaodong peninsula, maintaining a tenuous landbridge between China and the Korean kingdoms.

[2] Archeological finds don’t support the view that the Qin were any fonder of human sacrifice than other Chinese states of the era. For example, a 7th century BC tomb in faraway Liujiadianzi, Shandong, contained at least 35 human victims and a sacrificed charioteer entombed in full bronze assemblage. Such abundance of victims is unusual in Qin tombs.

[3] And was himself the descendant of ministerial, rather than old Zhou aristocracy, clans.