Quick Take: The Einstein Paradox, or Why Geniuses Often Suck at Politics

It turns out that it's pretty easy to be less wrong than Albert Einstein

(This Quick Take is free. About two-thirds of my post, those of the History of Mankind series, are for paying subscribers only. Don’t hesitate to comment and let me know what you think I got wrong, or right or whatever: the chance to get that kind of feedback from a larger audience precisely is one of the main reasons why most of my Quick Takes are free.)

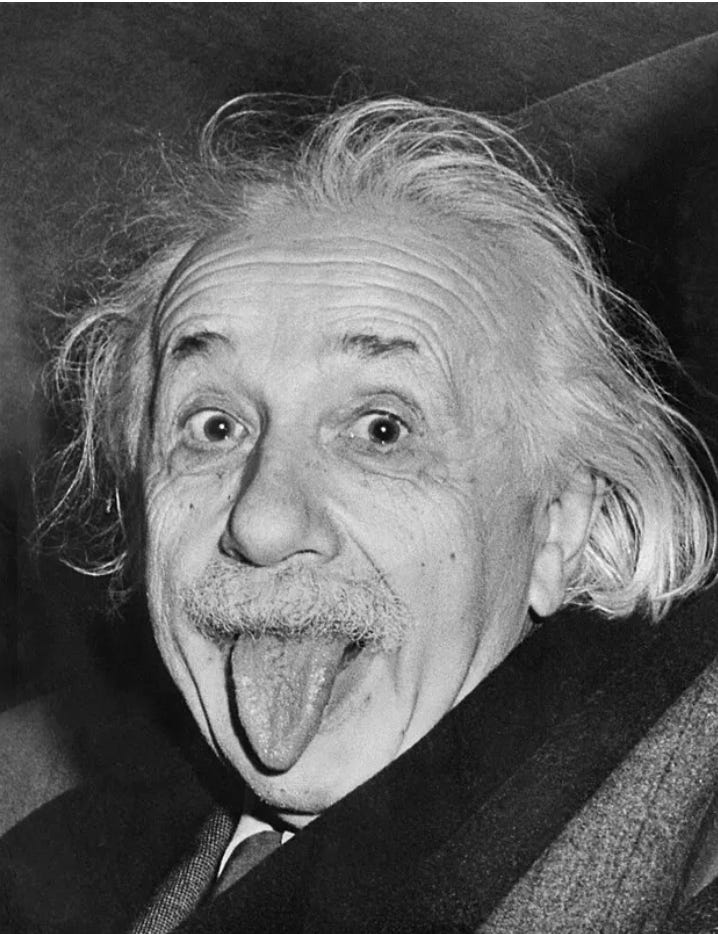

If you read anything at all about science, you will come across praise for Albert Einstein, commonly depicted with Charles Darwin as one of the can-do-no-wrong fathers of modern progress and technology.

Arguably, Einstein gets a free pass even more often than Darwin, a man who rarely put a foot wrong in his life and, when he thought he did, obsessed about the issue endlessly. When one reads about Darwin, one comes pretty convinced that he was a thoroughly decent person who was not perfect, certainly, but perhaps only because God (or the teenager running the simulation for his high school project that is our universe) will not grant perfection to mere humans.

Einstein, on the other hand, was a pretty indecent person who was wrong all the time in his life, often dangerously so, never apologized for anything and still got enough good PR to have his face stamped on T-shirts — so, to this day Einstein’s foibles are systematically hushed by science popularizers. Not the same case.

Take general relativity, the (well-deserved) foundation of Einstein’s enduring fame. Einstein did so much to move physics forward with this huge theory that it’s just shocking to see everything that he got wrong. As Jason T. Wright, a Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics at Penn State, argues here, general relativity was so hard to understand that even Einstein wasn’t sure what it predicted: he got the deflection of starlight wrong the first time he calculated it; and then he wrote a paper saying gravitational waves don’t exist — when the fact is that not only they do exist, but they are probably the only logical conclusion of general relativity.

In addition, Einstein got so many things right because he, like so many before him, was standing on the shoulders of giants — giants who are much less popular than himself.

Relativity wouldn’t hold up at all without the contributions of Hermann Minkowski, whose name recognition is minimal. Einstein’s entire work, as it’s very well-known among historians of science and very little known among the lay public, was built on the equations of Scotland’s James Clerk Maxwell, the basis of electrodynamics, as they show that electricity and magnetism are two aspects of a single force.

We should add the work of Jules Henri Poincaré to that mix, as he worked on predecessors to many of Einstein’s theories. Poincaré remarked on the apparent “conspiracy of dynamical effects” which caused apparent time and distance to alter according to the speed of an object following an 1887 experiment performed by Albert Michelson and Edward Morley that failed to obtain the results anyone at the time expected.

Under conventional Newtonian physics, light travelling in the direction of the Earth’s rotation around the Sun should have appeared to have a different speed from that of light travelling at right angles. Still, it remained resolutely constant, as Poincaré observed. Distances compress and time slows enough to make the velocity of light stay constant, he pointed out.

Einstein’s later paper on general relativity only served to seal the prohibition on travelling faster than light; but Einstein did add a key insight to that notion: that it then must follow that the speed of light is the universe’s sole constant (now, since the Big Bang included much faster speeds, apparently) and that nothing material can move faster than light; that means that time and space are malleable, and thus gravity pulls space and space drags you.

That’s why Einstein’s stance against gravitational waves makes little sense: the logical conclusion of his own insights is that gravity doesn’t really exist as a force of nature. We can keep referring to gravitation, not as a force, but only as a shorthand for the effect of the four-dimensional curvature of space-time that actually brings masses together.

However, Einstein won his Nobel Prize not because of that central idea of general relativity but largely because of his discovery that a beam of light is not a wave but rather a collection of discrete wave packets. This is a key insight leading to quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle, God’s dice and the notion that electrons are not really orbiting protons in the atomic nucleus but occupying “slots” — again, all conclusions that Einstein disliked completely and argued against for decades.

Einstein was wrong on so many things related to his field of expertise that it’s hard to keep track: for one, he thought that nuclear weapons would be impossible to build (he saw them built well within his lifetime, by scientists less august than himself). Einstein also rejected the theory of continental drift, believed in a static universe that would’ve been dynamically unstable (though he did quickly reverse himself once he saw Hubble’s data), gave terrible arguments against the existence of black holes, doubted the fundamental nature of quantum indeterminacy and entanglement and mostly wasted his last decades pursuing a unified field theory that ignored not only quantum mechanics and even the nuclear forces.

Myths have built upon Einstein’s statues to a worrisome extent: the frequently cited first empirical testing of general relativity, during the 1919 eclipse, wasn’t the astounding success that many trumpet. In reality, the results from the observation didn’t prove the theory, because of systematic error in the use of telescopes, bad weather and inconclusive conclusions.

This has been known for quite a long time. It was first stated in “Gravitation versus Relativity” (1922), by Charles L. Poor, and restated in Chapter Two of “The Golem: what you should know about science” (second edition, 1998) by Harry Collins and Trevor Pinch. Still, it’s easy to find admiring references to the 1919 eclipse testing, together with an entire edifice of Einsteins’ quotations, real and fake, that seek to prove his genial insight on everything under the sun.

As this Aeon article notes, Einstein is frequently quoted on a wide variety of non-scientific subjects, including education, intelligence and politics (he was offered the presidency of Israel, which he declined, in 1952), religion, marriage, money and music-making:

On education we get: ‘Education is what remains after you have forgotten everything you learned in school.’ On intelligence: ‘The difference between genius and stupidity is that genius has its limits.’ On politics: ‘Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.’ On religion: ‘God does not play dice.’ On marriage: ‘Men marry women with the hope they will never change. Women marry men with the hope they will change. Invariably they are both disappointed.’ On money: ‘Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.’ On music: ‘Death means that one can no longer listen to Mozart.’ And on life in general: ‘Things should be made as simple as possible but not any simpler.’ Only the quote about dice can be attributed without a doubt to Einstein.

It’s significant that this adoration is directed to a man who, in his personal life and opinions, was hardly a model. A pioneering virtue-signaler, Einstein kept a diary between October 1922 and March 1923, in which he muses on his travels, science, philosophy and art. In China, the man who famously once described racism as “a disease of white people” describes the “industrious, filthy, obtuse people” he observes, as The Guardian explained here.

In the diaries, Einstein notes how the “Chinese don’t sit on benches while eating but squat like Europeans do when they relieve themselves out in the leafy woods. All this occurs quietly and demurely. Even the children are spiritless and look obtuse.” After earlier writing of the “abundance of offspring” and the “fecundity” of the Chinese, he goes on to say: “It would be a pity if these Chinese supplant all other races. For the likes of us the mere thought is unspeakably dreary… A peculiar herd-like nation [ … ] often more like automatons than people.”

In Colombo in Ceylon, a place that rarely got the best out of colonial-minded Europeans, Einstein writes of how the locals “live in great filth and considerable stench at ground level” adding that they “do little, and need little. The simple economic cycle of life.” These are the raw, prejudiced, irrelevant, uneducated opinions of a middle-class man with little to no knowledge of politics or history, and no particular capacity to apply his intellect to those subjects.

And thus we finally arrive at socialism. Einstein wasn’t your average, clueless apologist of Soviet genocide. He was much more than that.

In “Red Millionaire: a political biography of Willy Munzenberg” (2018), Sean McMeekin notes that Einstein was among the most prominent cronies of Munzenberg, the controller of international Communist front organizations in the 1920s and 1930s who used his “formidable talents in the black arts of propaganda” to spread Stalinism across the globe:

At the height of his influence, Münzenberg controlled from his Berlin headquarters a seemingly invincible network of Communist front organizations—charities, publishers, newspapers, magazines, theaters, film studios, and cinema houses—which stretched, on paper at least, from Buenos Aires to Tokyo. Many of the interwar period’s most famous intellectuals—Upton Sinclair, Henri Barbusse, Albert Einstein, Bertolt Brecht, and John Dos Passos—came under his ever-expanding organizational spell.

Einstein was deep into this organization. In May 1943, he was among the hosts of the poet Isaac Fefer and the famous Yiddish actor Solomon Mikhoels, during their seven-month Soviet flag-waving tour of North America and England, as noted in “In Stalin’s Secret Pogrom. The postwar inquisition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee,” edited by Joshua Rubenstein and Vladimir P. Naumov.

Eventually, the pictures that the pair took in New York with the likes of Einstein, Robeson, La Guardia, Chaplin and Menuhin were used in evidence against them: in January 1948, Mikhoels was ordered to go to Minsk, ostensibly to review a play for the Stalin Prize. He was abducted and killed by the secret police; his body was dumped on a snow-covered street and his death announced as a traffic accident. In a conjunction exquisitely characteristic of Soviet Socialism, he was given a state funeral while his murderer was secretly awarded the Lenin Prize: and Einstein never made an objection or remarked upon Mikhoels’ past existence ever again.

Einstein did have a reflection on the sustained bout of murder and destruction he witnessed in the 1940s: “Only the creation of a world government can prevent the impending self-destruction of mankind,” he wrote around 1950. Good to know what we should avoid, Albert, thanks for the directions.

*

So you may be thinking: fine, Einstein was only human. He got a lot of things right, very, very important things for which mankind is indebted to him. And he got a few things wrong, maybe a lot of things. So what’s the Einstein Paradox? Is that it?

No. I don’t really care that Einstein was wrong so often about science. Physics is hard. Even if we were to admit that Einstein was the greatest physics genius of modernity (which is not certain), his edge over the second-greatest genius, whoever you pick, would be smallish. Science is a collaborative effort. Like I said before, Einstein was standing on the shoulder of giants and, when trying to go where nobody else had gone before, he was mistaken a lot.

That’s not a big deal. I can understand that. I don’t like it when science popularizers present him as this perfect man of genius and prefer to forget about such mistakes, but Einstein’s contributions to physics certainly are more important than those mistakes. We certainly shouldn’t assess writers on the basis of their worst books.

To me, the biggest problem was everything else, and that’s where the Einstein Paradox enters. People who succeed in sciences typically are extremely smart, and obsessive, and they have devoted much of their teenage years and early adulthood to solving incredibly difficult problems that most humans can’t even comprehend. They have no time to delve profoundly on topics related to humanities: history, politics, literature. To them, with some justification, those are small potatoes.

Alas, these people, at some point in their lives, decided that they must have opinions. We are in the democratic era, and in the democratic era we citizens are supposed to have opinions, indeed we are mandated to do so: how can we, otherwise, know whether it would be best to vote for the unqualified lady who slept her way through the ranks of one party or for the “convicted felon” who leads the other? So many options!

This happened to Einstein too. And, like many other of his ilk and generation, Einstein read the New York Times and a couple of fashionable books on politics and history, and decided that such inputs were more than enough for his superior IQ to conclude that Communism was the way of the future. A bit like when my mind, untrained in physics, fills with new (and useless) theories of quantum reality after I watch a few PBS Space Time videos.

There are many such cases, and this happens to this day. That’s the Einstein Paradox: that extremely smart men of science very often have the most stupid, moronic political opinions. Because they don’t know shit about politics or history, they haven’t the faintest idea of how modern states function, and they have convinced themselves that they do.

This is not about Einstein, but rather about the danger of holding an opinion on a topic which you have not researched for decades. People make political choices with incomplete information, then become emotionally invested and unwilling to pay attention to evidence that contradicts a preference. This tendency is easy for demagogues and journalists with an agenda to exploit.

Even Einstein didn’t know what he didn’t know!