Athens' Golden Era

A History of Mankind (111)

Welcome! I'm David Roman and this is my History of Mankind newsletter. If you've received it, then you either subscribed or someone kind and decent forwarded it to you.

If you fit into the latter camp and want to subscribe, then you can click on this little button below:

To check all previous newsletters in the History of Mankind, which is pretty long, you can click here.

In power, Pericles presented himself as an unrelenting imperialist from the get-go. In 457 BC, Athens took the richest 100 Locrians as hostages to ensure that region’s allegiance to the Athenian-led Delian League[1].

In a gesture that combined scholarship with cruelty, Pericles decreed that Locri would pay tribute through a thousand years in expiation of the misdeeds of the Locrian Ajax at Troy, as reported in the Iliad – two girls from their number to face death or temple-service at Ilium, at first for life, later annually.

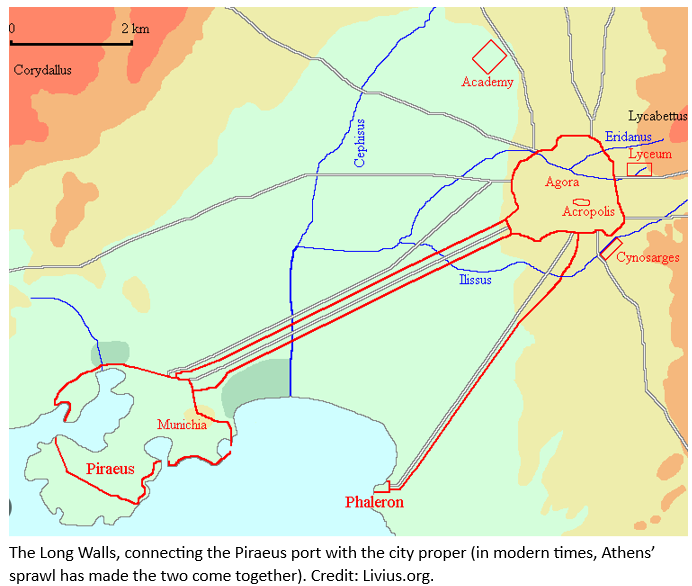

A stonemason by profession, Socrates may have personally benefited from Pericles' investment policies, or at least fellow stonemasons did. Old Athens had been burned to the ground by the Persians after the battle of Thermopylae, and Pericles reinforced his power by continuing a comprehensive plan of public works started under Cimon, which eventually led to the construction of the Parthenon between 447 BC and 438 BC, as well as that of the Long Walls connecting the city to the Piraeus port, so it could withstand a military siege.

Pericles also used the tribute paid by the Athenian League to help his lower-class political base, by setting up the so-called “misthoi” system of compensations for service in public positions, so that the poor people that supported his faction would get access to public salaries.

These are Pericles’ greatest triumphs. The misthoi, and related payments for jury duty, did much to deepen lower-class participation in Athens’ democratic system, but still under a significant degree of control[2]; and also at the cost of creating a solidly pro-Pericles constituency that essentially accepted the first citizen’s word as law for decades to come, re-elected him to his position on an almost annual basis, and hounded his enemies for him.

Pericles surrounded himself by the best and brightest, whom he regaled with his wealth and influence. But he relied on the most servile to man the city’s administration for him: men like Stephanos, a sycophant who proposed decrees on Pericles’ name[3], or Metiochos/Metichos, a reliable Pericles’ crony who occupied a variety of positions and was described as a jack-of-all-trades[4].

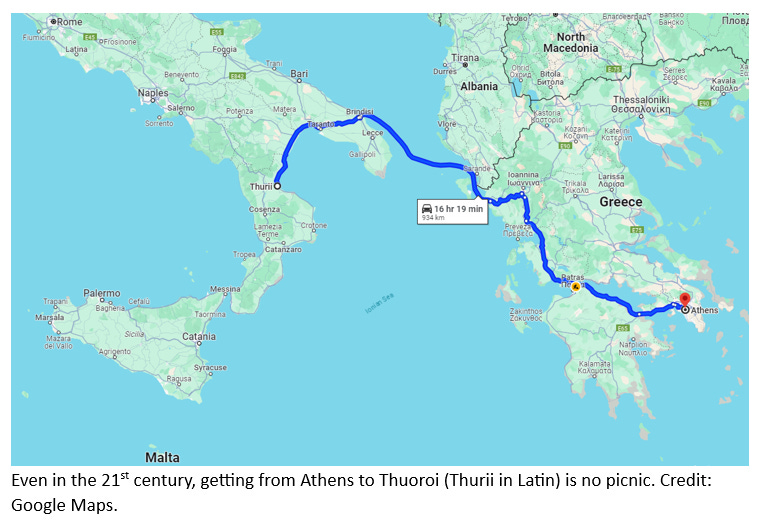

Lampon, another Pericles’ operative, was delegated by the great man to lead the newly-found colony of Thouroi in Magna Greece, one of Athens’ biggest projects before the Peloponnesian War, in what many contemporaries saw as an effort to deflect any blame for problems there.

Despite his overwhelming power, Pericles couldn’t stop all criticism of his policies, and found ways to allow some to let off steam. In a famous example, he was once insulted on the streets by some poor citizen, who followed Pericles all the way to his home, unable to shut up. Then, seeing that it was late at night, Pericles ordered one of his servants to help the man back to his home.

Even as he avoided getting caught up in petty disputes, Pericles used political capital he had accumulated to twist the law to favor his well-known non-Athenian lover and brothel-keeper Aspasia, and turn Athenian bully-style leadership of the Delian League into full-on imperialism. Socrates and other observers[5], disgusted by the corruption that Pericles' policies entailed, came to strongly dislike democracy and look for alternatives.

Around 450 BC, Pericles' teacher Anaxagoras was put to trial for impiety, a very common Athenian accusation[6]; even though (or perhaps because of) Pericles spoke in his defense, Anaxagoras went into exile in Lampsacus[7]; in any case, the charges may have been political, owing to his association with Pericles, if they were not fabricated by later ancient biographers.[8]

By 449 BC, peace with the Persians was followed by widespread revolts against Athenian imperialism, crushed by Athenian troops first in Euboea, and then in Samos in 440-439 BC; there, the Athenians made use of sophisticated siege equipment unlike anything seen in the East and comparable only with the best deployed in China[9] for an important victory.

This victory prompted a sister of Cimon, a women who remained an unrelenting enemy of Pericles, to complain bitterly that Pericles “had a lot of brave soldiers killed, not for fighting the Phoenicians or the Persians, like my brother Cimon, but to subdue a city that was our ally.”

According to Plutarch, the talk in Athens was that it was Aspasia, who came from Miletus, who pushed Pericles to attack Miletus’ old foe Samos, and that Pericles only gave way to gratify her; others have gone as far as blaming Aspasia for the later, and much more destructive, Athenian war with Sparta.

Regardless of the veracity of Aspasia-related gossip, the fact remains that Pericles’ democracy, a light of freedom for the people, was a prison for the peoples, paid for by the peoples, overseen by his street gangs and assemblies crammed with his clients and cronies. At the top was a man who found way around Athens’ rules against political mandates of over a year by having himself reappointed general annually from 443 BC to his death – in effect, becoming the first military dictator who claimed to protect democracy, and not the brightest or most efficient.

This light of freedom flickered quite notoriously too: it was at the height of Pericles' power, in the mid-430s BC, that the so-called decree of Diopeithes (a seer) was passed to curb impiety and target those who did not acknowledge divine things and those who taught rational doctrines relating to the heavens, like the already exiled Anaxagoras.

Many would be caught in this net, particularly Pericles’ political enemies, including the tragic playwright Euripides – who was acquitted from the charges – and Euripides’ friend Socrates, who in the end wasn't.

In 432 BC, Pericles’ blatant militarism led to the campaign and Battle of Potidaea, in which an already aging hoplite named Socrates fought with distinction against Spartan allies, next to the young aristocrat Alcibiades, who was then about eighteen. Alcibiades got an aristeia, a prize for bravery, but argued that it should have been for Socrates, who saved him while wounded — the start of a long relationship that endured long after Pericles was gone.

[1] An arrangement very similar to the NATO of the 20th and 21st centuries, created in 478 BC.

[2] Even though the low-born were in theory allowed to speak in Athens’ public assemblies, in practice there were complex arrangements and traditions so that only the oldest and most relevant citizens spoke with any frequency. On top of that, in 461 BC Ephialtes passed a reform that made public speeches in assemblies prosecutable, and established penalties including the loss of civic rights; Pericles apparently kept this reform in place under his rule.

[3] The activities of this Stephanos, and others like him, may explain why “sycophant” first became an insult/legal term for “abusive prosecutor” (prosecutions for “sycophancy” eventually became legal in Athens, albeit limited to six per year, as Friedman explains in “Legal Systems... “ pp. 262-263) and later a byword for courtier and leader-pleaser.

[4] “Metiochos is a strategist, Metiochos inspects the streets, Metiochos controls the bread, Metiochos controls the flour. Everything depends on Metiochos, Metiochos will regret it...This Metiochos was a friend of Pericles and he used, it seems, the power he owed him in a weary and jealous way" (Plutarch, “Political precepts”) Nothing else is known of this Metiochos, who shared a name with one of Miltiades’ sons, who was a hostage in the Persian court and became a sort of Persian nobleman according to Herodotus, and who was extremely unlikely to be same man. This Persianized Metiochos later became a legendary figure in Graeco-Roman literature, as the protagonist of one of the first prose novels in the Western literary tradition, “Metiochus and Parthenope,” a romance that survives only in small fragments but that is referenced in several other works. In the romance, the two protagonists fall in love in Samos. A Persian version of the novel, “The lover and the virgin,” became popular first in the Persian empire and later, rewritten, in the Islamized Baghdad of the 9th century AD, leading to multiple other rewrites and adaptations across the Islamic world.

[5] Plutarch would later write: “Many others say that the people was first led on by him into allotments of public lands, festival-grants, and distributions of fees for public services, thereby falling into bad habits, and becoming luxurious and wanton under the influence of his public measures, instead of frugal and self-sufficing.”

[6] In every case of which we have details about an accusation of impiety, the charges were simply a smokescreen to have the person charged for some other reason, normally for political expediency. In this case, Diogenes Laertius reports the story that he was prosecuted by Cleon for impiety, but Plutarch says that Pericles sent Anaxagoras to Lampsacus for his own safety after the Athenians began to blame him for the Peloponnesian War, which makes a million times more sense than believing that Cleon and his cronies were concerned about Anaxagoras' pre-scientific speculations.

[7] Anaxagoras eventually died in Lampsacus, having impressed the locals like he impressed Pericles: the citizens erected an altar to Mind and Truth in his memory, and observed the anniversary of his death for many years.

[8] One of the main reasons why many balk at calling Anaxagoras a sophist is that there's no evidence that he charged for his teachings: but the man was friends with Athens' most powerful man, so maybe he didn't even need to. Also, Protagoras was in a very similar position and he is frequently described as a sophist.

[9] As argued by Larry Bellshaw in “Siege Warfare in Fifth-Century Greece,” (2021) Academia Letters, Article 833. Bellshaw notes that circumvallation like that later used, for example, in the Athenian Expedition in Sicily, was time-consuming and Greeks typically used siege mounds, as was usual in the East; battering rams may have been invented for the siege of Samos, and were later used elsewhere, enhancing Athens’ reputation for siege warfare. However, the arms race was on: a primitive form of flame-thrower that could be used against combustible defenses, such as wooden walls, was used by the Boeotians employed such a device in 424 BC to recapture Delium from the Athenians; Thucydides records that in 427 BC Nicias captured Minoa for Athens with the aid of unspecified siege engines mounted aboard ships. In response, crenellated parapets and counter-walls became commonplace.