Rome's Ptolemaic Game in Egypt

A History of Mankind (195)

To check all previous newsletters in the History of Mankind, which is pretty long, you can click here.

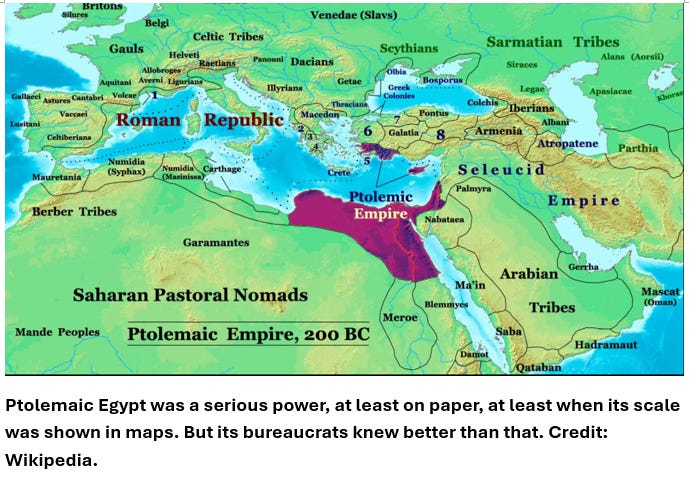

While the Seleucids, by and large, remained warriors to the last, the Ptolemies by the 2nd century BC had become an often-quoted example of decadence and indolence. Ptolemy IV, the accidental victor of Raphia, established a Dionysian community of party-goers and heavy drinkers at his court; and his son Ptolemy V (r. 204-180 BC) may have actually been poisoned towards the end of his reign when he pondered a campaign the Seleucids, a prospect that apparently terrified the court.

In fact, the famous Rosetta Stone was inscribed during Ptolemy V’s reign, proclaiming tax breaks for the Egyptian priesthood as a way to rally this important constituency to the monarchy’s side after a series of rebellions: since yet another war with the Seleucids may have been seen as many as an unneeded expense that threatened this delicate understanding with the priests.

There was an element of exaggeration in this legend of Egyptian sinfulness, and Egypt did take advantage of Roman hostility towards the Seleucids to weaken them further. But the realities of Egyptian politics under what remained a foreign dynasty supported by foreign colonists and by a foreign power (Rome) made it easier for everyone to have pleasure-seeking figureheads as kings, since their inaction limited the chances of causing either an internal crisis or a deadly clash with the kingdom’s Roman patrons.

This actually was a wise course of action. When Cleopatra VI, the last Ptolemy pharaoh, meddled too much in international politics a century later, it was that same meddling that led to the dynasty’s downfall.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A History of Mankind to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.