To read previous newsletters in the History of Mankind, which is pretty long, you can click here. Make sure to become a paying subscriber because they are all pay-walled.

The last great Pagan thinker, the philosopher-king Marcus Aurelius (121-180), no friend of the Christians, represents the final gasp of Stoicism as a philosophical system rather than a habit.

Wary of the rising influence of the new sect, Marcus Aurelius went after the Christians hard, same as most of the following emperors, and his two-decade reign was remembered as a time of peak Roman power and influence, despite costly military stalemates. His death marked the end of the so-called Pax Romana and the start of an era of troubles that was quickly accelerated into chaos after the murder of his unstable son, Commodus, in 192.

Like Seneca the scion of a wealthy family from Corduba, in southern Spain, Marcus Aurelius – Hadrian’s grand-nephew – grew up among the aristocratic villas on the Caelian Hill, an upscale neighborhood in Rome. This gave him an outlook similar to that of Siddhartha, the founder of Buddhism who was astonished to see poverty and ugliness when he emerged from his cocooned upper-class youth.

Marcus Aurelius spent much of his teenage years in a Greek philosopher cloak, under the influence of his Greek teacher Diognetus, and for a while tried to sleep on the ground to get in touch with the hardness of reality. His accession to the throne was uncommonly lucky: at an early age, he was appointed successor to the throne at one remove by emperor Hadrian, together with Lucius Verus, Hadrian’s adoptive grandson, and their predecessor Antoninus – who lost his two natural sons in early childhood – respected the arrangement.

While not a warrior himself, Marcus had a knack for appointing good generals, and had the time to write (in Greek) his “Meditations,” the book that made him more famous than any of his policies, in Rome and during trips to dangerous borders where he supervised military operations. Like all his predecessors stretching back to Vespasian, he was also an effective administrator with good ideas: almost certainly, he was the one who sent the first Roman embassy to China, a bold if eventually pointless move.

Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, who was younger than Marcus by a decade and acted as a junior emperor, inherited an empire that was in worse shape than it superficially looked. A Parthian move to secure control over Armenia as Antoninus lay dying in 161 triggered one of the most ridiculous Roman campaigns ever: the Cappadocian governor – advised by cult-leader and teenager rapist Alexander of Abonoteichus – led a legion across the Armenian border, where it was surrounded and destroyed within three days.

As barbarian raids across the northern borders tested Antoninus’ well-prepared defenses, another Parthian defeat of a Roman army triggered the deployment of massive reinforcements to the East, where full-on war broke against the Parthians. This presented a good opportunity to make some sense of Hadrian’s unique arrangement of a double-emperorship, so that Lucius was sent to lead the troops and Marcus remained in Rome.

The five-year war, like most Roman-Parthian clashes, was a confusing affair that didn’t lead to significant gains for any side. Lucius spent most of it in Antioch, drinking and enjoying the company and good-looking women, while the Roman legions successfully advanced into Armenia in 163 and into Mesopotamia in 165. The Romans sacked the twin Mesopotamian capitals – Ctesiphon, preferred by Parthian rulers, and the Greek city of Seleucia – and contracted some kind of a plague there, which they took back into the empire’s borders.

FROM THE ARCHIVES:

The Parthian Threat

To read previous newsletters in the History of Mankind, which is pretty long, you can click here.

Armenia remained a Roman vassal briefly, while most of Mesopotamia had returned to Parthian control by the end of the war in 166. The so-called Antonine Plague, likely an outbreak of proto-smallpox, was a more important aftereffect from the war: hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, died of the pestilence in the Roman Empire, unknown numbers in Parthian lands. The plague was also persistent, and new outbreaks were reported in years and even decades to come – Lucius Verus himself, who escaped contagion in the East, may have died of the plague in 169 while campaigning against the Marcomanni in Germania.

For a while, Cassius Dio reports, up to 2,000 were killed daily in Rome by the plague, estimated to have led to the deaths of a quarter of all infected; in 178-179, mortality at Socnopaiou Nesos in Egypt reduced the number of taxpayers by about a third in two months1, and the sickness remained deadly in Noricum in 182.

The plague may have been driven by the growth of large urban centers across the empire. Following widespread concerns about Italy’s poor demographic future around the turn of the millennium, emigration and rising fertility rates had combined to fuel a population explosion in the peninsula and particularly on the west of the empire, with more available land and decades of peace only rarely interrupted by barbarian raids.

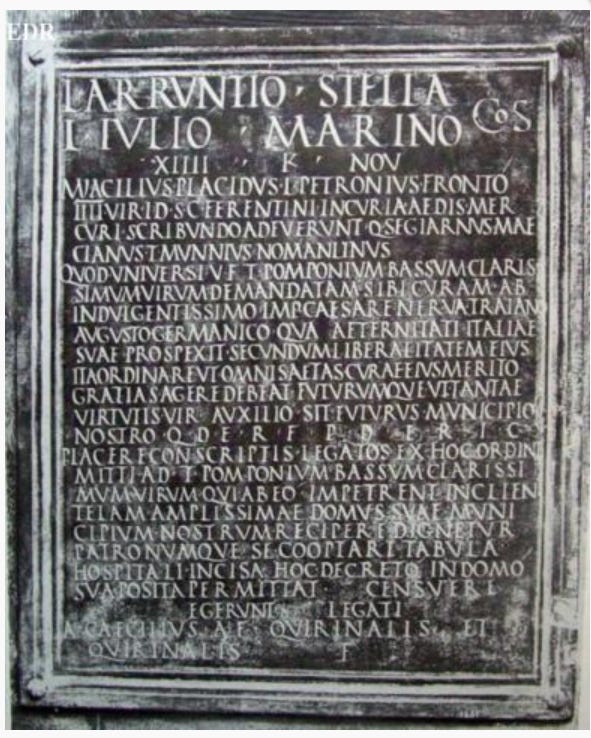

Under Nerva and Trajan, a large-scale system of so-called alimenta subsidies2 had been established to help farmers with freeborn children3. This looked to secure the flow of Italian recruits for the legions (given that most Italian legionnaires were of rural extraction) and maintain a land-owning lower class to balance the power of large landholders – who had again amassed properties as they took advantage of a decline in senatorial purges since Vespasian’s times.

Alimenta weren’t particularly successful for either purpose, due to connected developments: the proportion of Italian recruits – who accounted for as many as two thirds of all legionaries in late Augustan times – fell steadily until by the end of the 4th century it was at less than 25%4; and this was partly because of renewed rural migration to cities and big towns, with the consequent deleterious effect on fertility, as urban centers presented more economic opportunities as well as appealing “bread and circus” compensations for the not-so-enterprising5. These combined trends resulted in what may have been the last significant urbanization drive in the area in 1,000 years, until European cities again refilled significantly during the late Middle Ages.

In the Italian countryside, in ever more Italianized Sicily and, to a lesser extent, elsewhere in the empire, the era of the “five good emperors” was also a golden era for the aristocracy, left in peace to work the magic of compound interest in a well-protected, enterprising empire, for as long as an absence of civil wars and disputes over succession negated the need for taking their assets. This was the era in which the old, Republican-era division between patricians and plebeians started to become superseded by that between Honestiores and Humiliores, new terms to denote distinctive legal status for distinctive classes across the empire.

It’s not a coincidence that the longest Roman name ever recorded – long names being a sign of well-established aristocracies with multiple ancestors that must be recalled – is that of Quintus Pompeius Senecio Roscius Murena Coelius Sextus Iulius Frontinus Silius Decianus Gaius Iulius Eurycles Herculaneus Lucius Vibullius Pius Augustanus Alpinus Bellicius Sollers Iulius Aper Ducenius Proculus Rutilianus Rufinus Silius Valens Valerius Niger Claudius Fuscus Saxa Amyntianus Sosius Priscus, a consul of the year 1696.

Unlike the similar upper-class prosperity of the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, this wasn’t based on enormous slave armies working the land, but on the rural landless who couldn’t find appropriate employment in cities – tenants left working other people’s land and paying their rents. The prosperity was also wide-ranging, since provincial manors and extant remains such as Philopappus Monument outside Athens’s Acropolis and the Library of Celsus at Ephesus7 are evidence of significant regional wealth. The Barbegal water mill complex near Arles, in southern Gaul, the largest in antiquity, may have produced up to 25 tons of flour per day and made a fortune for its unknown owner.

In the end, the Antonine Plague, not barbarian attacks or Parthian skullduggery in Armenia, was the first serious challenge to this state of affairs, and perhaps marked the end of the urbanization period; the sight of piles of dead bodies being carried out of cities for cremation may have fueled Marcus Aurelius’ melancholy.

Renewed barbarian aggression in the north didn’t help matters. Sensing weakness and taking advantage of military corruption networks created during Antoninus’ placid reign, funneling weapons to and taking bribes from barbarians, Germanic and Sarmatian tribes pressed along the Rhine and Danube frontiers, especially the exposed open wound that was Dacia.

From 162 on, the empire was repeatedly invaded by the barbarians; in 166, the Marcomanni, Roman clients for well over a century, joined the Lombards in a rampage deep into Roman territory, and the Carpathian Costoboci went as far as raiding Macedonia and northern Greece, sacking Eleusis. In Ravenna, barbarian auxiliaries who had settled there with their families, as an earlier concession to split some tribes from anti-Roman coalitions, rose against the Romans and took temporary possession of the city – which eventually led to a banishment of all northern barbarians earlier settled in Italy.

Hard pressed, Marcus Aurelius was the first (but not last) emperor to sell gold vessels and artistic treasures of the imperial palace to finance campaigns. In 168, after some victories pushed enemies back across the border, he triumphantly announced a revaluation of the denarius, by increasing its silver purity slightly, to 82%; two years later, he reverted back to the previous silver levels as more barbarian attacks required more coin to pay troops.

Aurelius' Meditations give the impression that he was a bit of a pedant, obsessed with his own conscience, and happy to be in his own company8. Aurelius' quotations sometimes make Epicurus sound like a deranged maniac in search for painful, convoluted truths: from “Waste no more time arguing about what a good man should be. Be one” to “All this visible world changes in a moment and will be no more” his philosophy is tailor-made to be distributed in the form of self-help snippets among the executive class.

With Aurelius, posterity obtained two philosophers for the price of one. The other one is Epictetus, once banished by Domitian; Aurelius was so fond of quoting his stoic predecessor – a rare case of a relatively late thinker from antiquity who didn't leave any writings of his own, Socrates-style – that he helped to turn Epictetus, previously close to unknown, into a household name for centuries to come.

It is only thanks to Epictetus’ student Arrian — who became close to Hadrian, Aurelius' benefactor — that we have a handbook with Epictetus's Discourses, allowing to see that Epictetus was a stoic through and through, but also that he was a bore who appears to have had no real grasp of how anything works: at one point, Epictetus is quoted by Arrian as meeting a man who tells him his marriage is going terribly; Epictetus’ supposedly wise response is that “people don’t marry and have children to be miserable, but to be happy instead.”9 Reading Aurelius' and Epictetus' forceful calls to find one's inner saint, it's easy to accuse stoics, and the latter wave of Hellenic philosophy in general, of naive dilettantism10.

Epictetus wasn’t, however, Aurelius’ only promoted historical celebrity. The Libyan Marcus Cornelius Fronto, one of the sharpest rhetoricians in Rome’s history, was friends with the emperor, to whom he wrote interesting letters in which Fronto, for example, described Seneca as a juggler of words, who mostly impressed children and the less learned – not necessarily a correct argument, but one expressed with great verve and color11.

The emperor also hired Galen, a famous physician from Asia Minor12, as court doctor, launching the career of perhaps the only of his contemporaries who became more famous than himself – even in his own lifetime, Galen was widely popular (Aurelius described him as “first among doctors and unique among philosophers”), to the extent that he had to write a book called “On my own books” to sort out forgeries and unscrupulous editions of his work. In that book, he complains that his servants were stealing private letters he had written to friends and circulating bootleg copies of them as medical advice13.

Throughout the centuries to come, Aurelius was, like Trajan and Hadrian and, to a lesser extent, Antonius, celebrated as a wise ruler to be imitated. Perhaps the only decision that he ever made that has been widely criticized was a break with recent tradition: instead of adopting somebody else to be his successor, he had his son Commodus succeed him in 180, an accession that represented the first time a son had succeeded his biological father since Titus succeeded Vespasian; and one that came close to never happening – Commodus was the only of Marcus Aurelius’ seven biological sons to survive to adulthood14.

Commodus, the son of a philosopher-king, may have been the least suitable person ever to take the Roman throne. Hated by pretty much everyone who had the misfortune to come across him, Marcus Aurelius’ efforts to given him a stoic education failed miserably, or perhaps succeeded admirably; two centuries later, the not always extremely reliable Historia Augusta wrote pointedly about his character, evident since early childhood:

“Commodus was nasty, dishonest, cruel, desirous, foul-mouthed, and corrupted. For he was already a craftsman in those things which were not proper to the imperial class, such as making chalices, dancing, singing, whistling, playing a fool, and acting the perfect gladiator. When he was twelve years old, he provided an omen of his cruelty at Centumcellae. For, when his bath was accidentally too cool, he ordered that the bath-slave be thrown into the furnace. Then, the slave who was ordered this, burned a sheep’s skin into the furnace, so that he might convince the punishment was performed through the foulness of the smell.”

Cit. R.P. Duncan-Jones, “The impact of the Antonine Plague,” in American Journal of Archaeology (1996). It’s hard to gauge the exact impact of the plague, partly because the famous physician Galen made his fame partly by treating it – so he had every reason to exaggerate how dire things were, as Colin Elliott argued (Op. Cit.) .

The more than fifty alimentary alimenta (foundations) established to provide monthly cash allowances to rear boys and girls are typically presented as perpetual loans at 5% annual interest secured on farmland, but these were not like bank loans because they were not repayable. As Temin explains (Op. Cit.): “They were compensation to the owners for establishing a perpetual charge, in effect a tax, on their land. Even absorption of the total cash compensation paid out by the state over ten to fifteen years, at most around HS 40 million, the equivalent of two senatorial fortunes, will have had little impact on the Italian markets in land and credit. The closest modern analogs are the British consols (consolidated annuities) established in 1751, which paid a fixed annual return but never came due.” Alimenta were complemented by private schemes, as noted by Jesper Carlsen, Op. Cit., p. 45.

Alimenta were – according to “The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire,” by Mikhail Rostovtzeff (1926) – the basis of a welfare program, with which “Trajan sought to come to the rescue of the city landowners, and perhaps of the peasants as well, by giving them cheap credit for the improvement of their lands and by helping them to educate, or rather to feed, their sons and, to a certain extent, their daughters.” That is, cheap credit, provided directly by the imperial treasury. Interestingly, only a 4th century source, Aurelius Victor, mentions that the funds were intended for poor families, which may be an anachronistic statement reflecting later Christian attitudes to charity: the difference between a broader, no-questions-asked program designed to help everyone, and a specific one targeting the poor only is, however, massive when it comes to assessing the alimenta and its scope, since it’s difference between a broader, basic income program and a limited top-up subsidy.

Cit. Turchin, “War and Peace and War.”

Pliny describes alimenta distribution in the city of Rome. In “Beneficial Symbols. Alimenta and the Infantilization of the Roman Citizen,” a paper in “Pleket” (Op. Cit.), Jongman notes that the beginning of the 2nd century saw the establishment in Italian cities of both private and imperial alimenta, endowment schemes to provide financial support for children; as Jongman adds, it’s clear that ”the allowances were generous, that they supported a large proportion of free children in the cities, and that many Italian cities had alimenta…Through the alimenta many citizen families received subsistence support on a level roughly comparable to the plebs frumentaria in the city of Rome.” There is inscriptional evidence for alimentary schemes in some fifty Italian towns.

The name is composed of 38 separate elements, of which fourteen are different sets of nominae. See Benet Salway’s "What's in a name? A survey of Roman onomastic practice from c.700 B.C. to 700 A.D" (Journal of Roman Studies 84), 1994.

The Philopappus Monument was built as a tomb for Gaius Julius Antiochus Epiphanes Philopappus, grandson of the last Commagene vassal king, deposed by Vespasian. The Library – the third largest in the empire after Alexandria’s and Pergamus’ – served as a monumental tomb for Tiberius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus (45-120), along with some 12,000 scrolls enclosed in the library’s extravagantly designed and decorated façade. Both were completed in the 2nd century. See “Live Like a King”: The Monument of Philopappus and the Continuity of Client-Kingship,” by Ching-Yuan Wu, in “Perceiving Power in Early Modern Europe,” ed by Francis K.H. So, Palgrave MacMillan (2016).

Modern figures such as Wen Jiabao, Bill Clinton and James Mattis have proclaimed themselves admirers, which gives a flavor of his intended audience: accomplished winners in the rat-race of life who feel sorry for the poor people who never made it to their own exalted heights, and who in addition would like to appear enlightened.

Epictetus, Discourses According to Arrian 1.11.

As Slavoj Zizek put it in “Event” (2014):” The Greeks lost their moral compass precisely because they believed in the spontaneous and basic uprightness of a human being, and thus neglected the bias towards evil you find at the very core of a human being: true Good does not arise when we follow our nature, but when we fight it. The same point was made in Richard Wagner's opera Parsifal, whose final message is: 'the wound can be healed only by the spear that smote it.'” There are much worse views on the subject of stoics. In “Orthodoxy,” (1908), the Catholic writer G.K. Chesterton probably had the worst possible opinion of Aurelius: "Marcus Aurelius is the most intolerable of human types. He's an unselfish egoist... A man who has pride without the excuse of passion... He gets up early in the morning, just like our aristocrats living the simple life get up early in the morning; because such altruism is much easier than stopping the games of the amphitheater or giving the English people back their land… Of all horrible religions, the most horrible is the worship of the god within.”

“What if the same meal is offered to two people and the first picks up the olives on the table with his fingers, brings them to his mouth, puts them between his teeth to chew them in the right and proper way, while the other throws them up high and catches them with his mouth open and then shows them off once caught with his lips like a juggler? Really, children at school would applaud at what was done and the guest would be entertained, but one will have eaten lunch properly while the other did tricks with his lips. So you say that some things are expressed cleverly and some with weight. But sometimes little silver coins are found in the sewer. Should we take over the job of cleaning the sewers too?” The letter is on the 19th century compilation “On speeches”; the translation is by Sententiae Antiquae, 16.4.23.

Having inherited early from his father, he travelled around the Mediterranean to learn his trade, and became an avid vivisectionist, and later an expert in anatomy.

Galen was incredibly prolific and may have written as many as 600 books altogether, many of them necessarily slim, almost all of them including mistakes regarding medicine and anatomy, in one sense or another. About 10% of all surviving Greek-language pages from antiquity are Galen’s. Six centuries earlier, Hippocrates of Kos – an earnest but very often wrong medical practitioner who went as far as recommending the sacrifice of puppies as a treatment against female infertility – introduced the Hippocratic Oath that has since been honored more in the breach than in the observance, since it includes renunciations of abortion and euthanasia. Hippocrates also introduced the idea of the four humors to medicine, four fluids that congeal together to form our flesh and organs, and which co-mingle in our veins in their liquid form; Galen would be the one to make this arrangement, fundamentally unsound, and the rationale behind the popular practice of bloodletting, world-famous. Still, he was highly influential on the history of science too, because of his insistence (particularly contra Asclepiades, his hated adversary) that empiricism, rather than authority, was behind his teachings. Curiously enough, Galen was a contemporary of Zhang Zhongjing, author of a "Treatise on Cold Pathogenic and Miscellaneous Diseases" that was about as effective treating illnesses as Galen’s own methods, and who was later considered the father of Chinese Traditional Medicine.

Marcus Aurelius had several daughters who married and had children of their own, so it’s pretty safe to say that he too is a common ancestor to all living people with any European ancestry in the 21st century.

Fascinating article - love the comparison between the young Marcus Aurelius and Siddhartha

His predecessors had the advantage of not having sons. In Rome, you could adopt a son, provided that you didn't have one. For him to adopt a son and declare his existing one not his heir would have been an insult to his ancestors.