Quick Take: You Won't Believe Who Saved More Jews from the Holocaust than Anybody Else

Franco's regime, under his direct instructions, saved over 40,000 Jews from certain death, and he's still not celebrated in Israel

(This is the second of several articles about Francisco Franco’s regime, ahead of the 50th anniversary of his death later this year. The first is here.)

Francisco Franco’s Spanish regime saved over 40,000 Jews from near-certain death in the Holocaust during World War II. And yet Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum in Israel that finds space to recognize Franco’s little helpers as Righteous Among the Nations, has never recognized Franco's own role. It makes one wonder.

That Franco ordered and directed these efforts is hardly a secret or new information that has been uncovered by resourceful scholars of Fascist Spain.

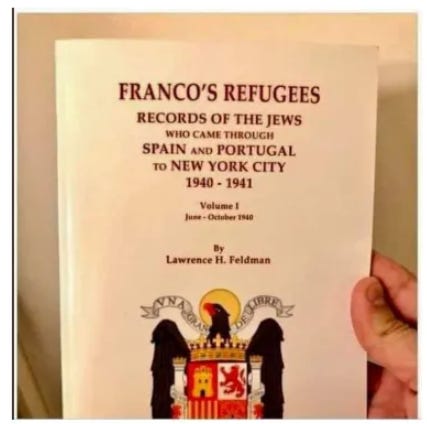

For example, a lot of detail can be found in a monograph on the subject — “Spain, Franco and the Jews,” published in 1982 — by Haim Avni, that I came across in a Spanish translation from the English in Madrid.

Here is an (incomplete) list of the employees of the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs that Avni mentions as involved in the work to save Jews from the Holocaust: Miguel Angel Muguiro, expelled from his post in Budapest for his harsh criticism of the Hungarian regime and his efforts on behalf of the Jews, replaced by Angel Sanz Briz in 1944; Giorgio Perlasca (who continued Sanz Briz's work in Budapest after the latter left for Switzerland that same year); Manuel del Moral, consul in Tangier; José Félix de Lequerica, ambassador to Vichy France; Bernardo Rolland, consul general in Paris; Eduardo Gasset and Sebastián Romero Radigales, consul generals in Athens; and Juan Palencia y Tubau, ambassador in Bulgaria, who went so far as to adopt two Jewish orphans, in their twenties, to save them, and received the Cross of Isabel la Católica for his heroism.

There are more lists: for example, that of nine Spaniards whose names appear registered in the Yad Vashem memorial among the righteous, most of them as officials of the Spanish state.

Still, Israel voted against Spain’s first attempt to join the UN on May 16, 1949, a few days after its own acceptance in the UN, helping to block an attempt by several Latin American countries seeking to overturn the diplomatic boycott imposed on Franco’s regime in 19461. Why they did it was explained in 1949, when Israeli President Abba Eban declared that Israel could not agree to Spain’s UN membership “because of the Franco regime’s association with the Nazi-Fascist alliance.”

Avni estimates that, in the first phase of World War II, nearly 30,000 Jews, most with visas for Portugal and beyond, escaped Europe through Fascist Spain. In the second half of the war, especially from 1942 onwards, the aforementioned Spanish diplomats and others provided papers and saved some 3,235 Jews from other European countries, plus 800 Spanish citizens, and the country accepted the passage of an additional 7,500 Jews in transit.

Did Eban know all this when he gave his speech at the UN? I’m going to bet that he didn’t. That’s why it’s important to set the record straight.

The record has been skewed for a long, long time. In July 2013, Malcolm Gladwell wrote an interesting and misleading profile in the New Yorker of Albert Hirschmann, a German economist who, along with American reporter Varian Fry, helped more than 2,000 Jews escape from Vichy France. A quick summary of the article could be: Hirschmann, great hero, Fry, even greater.

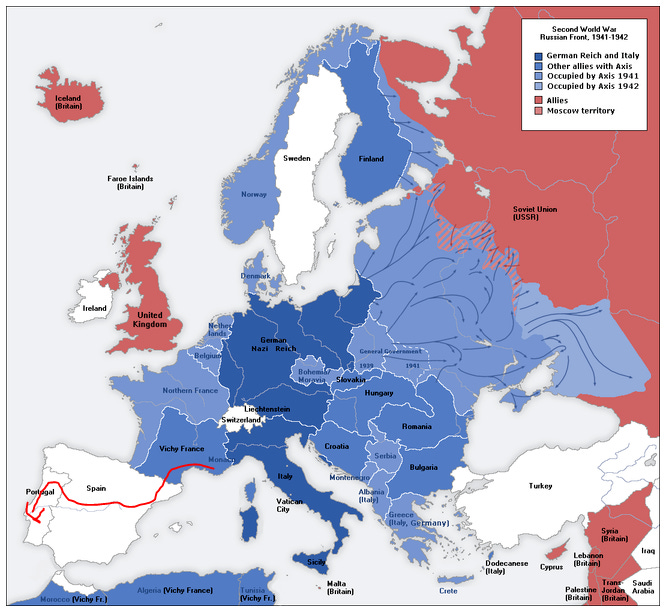

The long profile struck me as misleading because of the way the famous Gladwell explains how those thousands of people, men, women, children, old people, arrived in the United States: Hirschmann and Fry hid them in villas in the south of France, and then they made it to Lisbon, where they took a boat to the United States. The word “Spain” appears only seven times in the text, and the word “Franco” once, and all those are references to Hirschmann’s time as a Communist volunteer in the Spanish Civil War.

In fact, in Gladwell's mental world, Spain does not exist. It is easy to see that almost all of the Jews helped by the Fry-Hirschmann network reached Lisbon after spending days or weeks or months crossing Spain, where they received assistance, shelter and food. I’m going to sketch a map for your (and Gladwell’s) convenience, showing the route from southern France to Lisbon along the roads that existed in 1941:

Contrast this with the case of Switzerland, another frequent target of refugees from Nazism. The adventures of Francoise Frenkel, a Jewish lady who managed to cross into Switzerland (after three failed attempts!) briefly became famous a few years ago through the efforts of Robert Fisk. And there is no criticism of the Swiss authorities in Fisk's account or Frenkel's own writings, only admiration for the humanity of the one friendly Swiss border guard who finds her in the forest and saves her life.

The reality, however, is that Switzerland turned back thousands of Jews at the border (between 10,000 and 25,000 according to the Swiss authorities themselves), sending them back to occupied Europe, often during the period when the Holocaust was already underway; on top of this, they collaborated with the German authorities to mark the passports of Jews with a “J” to alert customs officers: which strikes me as truly Teutonic attention to detail.

The case of Paul Grüninger (1891-1972), chief of police of the canton of St. Gallen, bordering Austria, is famous in Switzerland (this is a bit like being Big in Japan, though). After the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria to the Third Reich (March 1938), many of the Jews living in the small republic tried to flee. The number of those who escaped between March 1938 and September 1939 exceeded 100,000, many of them via Switzerland:

When the government of Switzerland, in agreement with Hitler's regime, took measures to stop the entry of Jews, such as requiring a visa (March 28, 1938) and accepting passports issued by German officials with a large J to identify Jews (April 1938), he ignored them… In the end, the Germans warned the Swiss that there was a breach in the border. The very democratic Swiss listened to the Nazis, investigated and discovered Grüninger. The federal government dismissed him in March 1939. In addition, the authorities of the canton of St. Gallen initiated a trial against him in January 1939 that lasted two years. In March 1941, he was convicted of falsifying public documents and failing to fulfill his duties. In addition to losing his job, he was also forced to lose his pension and pay a fine and court costs. The court acknowledged the altruistic nature of his actions, but as a civil servant he had to obey the instructions of his superiors… A media campaign forced the federal government to send a private letter of apology in 1970, although it did not reinstate him in his post, restore his rank or grant him a pension. In April 1971, a few months before his death, he was awarded the title of Righteous Among the Nations.

These events have not prevented many from praising Swiss authorities for their role in saving Jews. The same is true of Sweden, stridently celebrated for Raoul Wallenberg's work in rescuing Hungarian Jews, despite its restrictive policy against Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi-controlled territories until 1942 — the year it became clear that Adolf Hitler would lose the war.

It should be noted that both Sweden and Switzerland were neutral, wealthy nations completely isolated from both WWII and the conflicts that spread across Europe during the 1930s. Spain, on the other hand, had been devastated by a Civil War that left almost half a million dead and much of the country destroyed, with food rationed for the local population until the 1950s. When Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, Spain was already on the brink of famine, and the continental blockade imposed by the United Kingdom after the French defeat in June 1940 only made things worse.

During those years, Spain received a million tons of imported wheat annually, and gasoline supplies at double or triple the market price, from the United States. Supplies became dependent on navicert certificates granted by the British government to the merchant fleets of neutral countries, as to avoid the embargo on Germany and the occupied countries. The dependence was total: as Carlton Hayes, the US ambassador, recounts in his memoirs “Wartime Mission in Spain” (1946) how, in April 1943 the airline Iberia ran out of gasoline for its planes and the United States only agreed to supply 320 tons a month in exchange for receiving information about the passengers on flights to Tangier, a key node of many espionage networks.

Despite these extreme conditions, Spain never closed its borders to war refugees, as Switzerland and Sweden did on occasion. Avni’s estimates about the number of Jews saved by Franco’s regime are in line with the consensus of researchers on the subject: the American Encyclopedia of the Holocaust estimates that some 30,000 people, mostly Jews, escaped France via Spain between 1939 and 1941 alone, and some 10,000 more over the remainder of the war. There are also higher estimates.

Among these refugees were Hannah Arendt, Marc Chagall, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Max Ophüls, Alma Mahler (who carried 17 suitcases, none of which were confiscated at the border), Arthur Koestler, Lion Feuchtwanger, and Hirschmann himself.

I’m not aware that any of these people ever had a word of gratitude for Spain and its authorities. This may be because, for many refugees, their stay was not a happy time. The ups and downs that some experienced can be seen on this page from Avni’s book (by those who can read Spanish):

Then there is the case of the philosopher Walter Benjamin, whose death has poisoned the historiography of Franco’s era. Benjamin committed suicide in Portbou, Gerona, on September 26, 1940, terrified by the possibility of being returned to the Vichy authorities.

The group he had joined to travel to Spain was allowed to continue on their way the next day, without any problem, like so many others. Avni writes that, in 1940, crossing the border was quite easy and many refugees without papers reached Barcelona without incident; those who were captured were interned in provincial prisons, under the usual legal regulations for illegal immigration, but never returned to France2.

Benjamin's case is also complicated by separate allegations that Benjamin may not have committed suicide, but rather been assassinated by Stalinist agents who knew that Benjamin planned to publish anti-Soviet writings from exile.

Regardless, Benjamin’s case is irrelevant to the facts about Spain’s official policy regarding Jewish refugees. Spain welcomed them. Most western countries would keep them as far as they could. Like the US.

On November 25, 1940, two months after Benjamin's death, US Secretary of State Cordell Hull received a request for help from Vichy French ambassador Gaston Henry-Haye, who described the arrival in Unoccupied France of thousands of "Israelites" who had been expelled from the German territories of Wurtemberg and Baden.

The problem was enormous, Henry-Haye explained, saying that Vichy France held three and a half million foreign refugees on its territory, from Armenians to Assyrians to Catholic Poles, and was short of food for them because of the British blockade. Henry-Haye asked the United States, which had diplomatic relations with Vichy, for assistance in enabling some of the refugees – particularly the German Jews whom the ambassador saw as most at risk – to emigrate to America, from North, Central or South.

The State Department took several weeks to respond. When the reply came, Hull very politely refused to comply:

“The laws of the United States regarding immigration are quite explicit and do not allow for much liberalization.”

In a letter sent by an aide to Hull to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the State Department explained the reason for the refusal: it was necessary to reject the “totalitarian blackmail” proposed by Vichy, which was under German pressure to expel refugees from continental Europe3:

“If we yielded to this pressure, the Germans would turn the remaining Jews of Germany and the occupied territories against the French, in the expectation that the French would in turn persuade this country and others in America to receive them.”

This was the attitude of Washington DC’s government on the eve of the Holocaust. Nothing special too: it had been that of many other "civilized" countries for years, such as Holland, as well as other countries of lesser international fame, like the Soviet Union; in “Bloodlands,” his classic 2011 study of the bloody borders between German and Soviet zones of influence, Tim Snyder explains (p. 144) how Stalin had rejected in 1940 the German request that the USSR keep two million unwanted Jews in Nazi Germany and occupied Poland.

This is important because I’ve seen some argue that Spain helped Jewish refugees to ingratiate itself with the United States. And yet at this point neither Washington nor anyone else wanted or valued such gestures; later on, they would appreciate them.

While such exchanges were taking place on the other side of the Atlantic, still in peace, hungry Spain was receiving refugees by the tens of thousands. This was the case particularly from June 1940, with the fall of Paris and the formation of the new Vichy regime.

The situation was somewhat paradoxical, given that Spain was not entirely neutral: when Italy joined the war, Spain declared itself “non-belligerent”, a way of satisfying both Franco’s allies during the Civil War and the United Kingdom, still in control of the seas and the supply of goods to Spain.

I’ve explained before why Franco refused to join the Axis. Still, he did believe that Adolf Hitler would end up winning the war and a year later he sent the Blue Division of anti-Communist volunteers to fight on the Eastern Front, as a way to cover all his bases and placate the powerful pro-German constituency within his regime.

The reason why Franco still went out of his way to help the Jews is not hard to understand if one knows Spanish history, but not many people do. In summary, Spain — having expelled its Jewish population in 1492 — had lost its early anti-Semitism over the intervening centuries.

The more fanatical elements of the regime were often anti-Semitic, and I myself wrote a paper in college on the sometimes crude anti-Semitism of the Falangist newspaper Arriba in the early years of WWII. This was, however, not just a minority position but one in direct contradiction with earlier state policy: in the 1920s, dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera actually allowed Sephardim Jews who could prove a connection to Spain to receive Spanish citizenship, a step that inspired a similar one passed in 2015, which I wrote about here in the Wall Street Journal.

José Antonio Primo de Rivera, Spain’s Fascist leader executed by the Republicans in 1936, had been just the most prominent of several intellectual forebears of Franco’s regime who rejected Nazi Germany’s racist policies, openly describing them as opposed to the Spanish tradition. Spanish Jews who converted to Christianity in the early modern era were not persecuted as racial enemies (unlike the case in Germany) although British propaganda later had a field day attacking Spain’s issuance of certificates proving no Jewish ancestry — while the British Empire, as always impervious to irony, set up two great monuments to white supremacy in South Africa and India.

Let’s be clear. Franco was no promoter of religious diversity: his victory in the Civil War did worsen the legal situation of Jews in Spain, as it returned Spain to the legal framework of the pre-Republican constitution of 1876, vowing tolerance for other religions but no specific protections. In the new Catholic state, synagogues in Madrid and Barcelona were closed and foreign Jews were pressured to leave Spain. At the same time, Franco wanted to save people whom he knew were under a serious, deadly threat.

At the end of 1940, when the also Fascist state of Romania asked Spain about the legal status of Jews in Spain, perhaps seeking inspiration for its own policies, the answer came in a verbal note, dated December 19, 1940, from the pro-German Ramón Serrano Súñer: this man, at the time Franco’s right-hand (things would change soon), explained that Spain had no anti-Jewish legal provisions of any kind.

The laissez-faire era for border crossings by refugees escaping France ended in August 1942, when Vichy authorities stepped up patrols to stop illegal crossings, revoked the issuing of exit visas and began sending foreign Jews eastward. On the 14th that same month, the American ambassador in Madrid, Hayes, informed his government in a cable that the Spanish Foreign Ministry had given instructions not to expel anyone.

In “La vie des francais sous l’Occupation” (1961), Henri Amouroux recounts cases of abuse against refugees at the border, almost always by Frenchmen: the middleman who killed several refugees after paying for their transport to Spain, the smuggler who killed a refugee on the road because he was unable to continue his journey, another smuggler who guided refugees directly to where the German border patrol was, and a smuggler who demanded more money from them en route. Similar stories are told in, for example, Lucien Greffier’s memoirs, “La mesadventure espagnole” (1946).

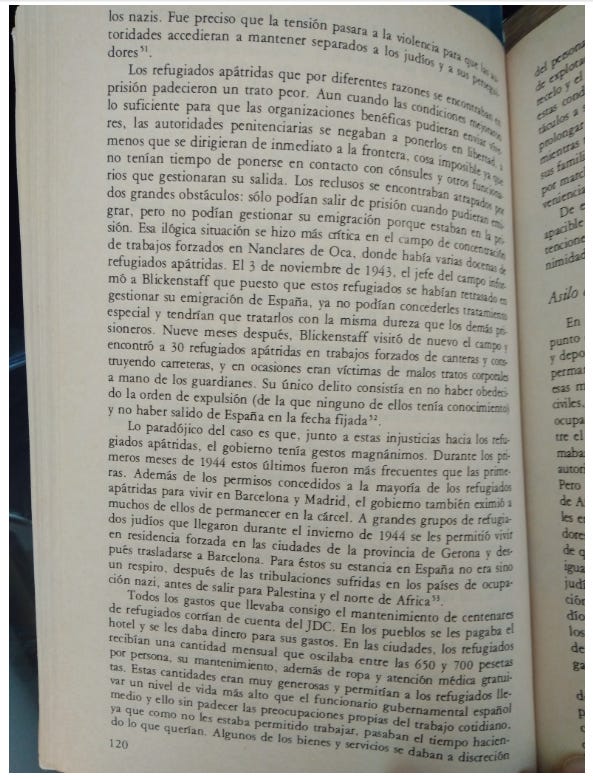

The situation became particularly dire with refugees stranded in Spain, as Avni explains:

There were cases of exploitation and the situation was sometimes aggravated by fraud among some refugees, and sometimes it aroused suspicion and hatred among the people who provided the aid. In these conditions of forced but comfortable unemployment, imposed by the obstacles to leaving Spain, some refugees were tempted to prolong their period of transit as much as possible, in the hope that in the meantime the war would end and they could return to France to look for their relatives and recover their property. Even refugees who were in a hurry to leave for Palestine or elsewhere were affected by the convenience of this temporary stay in Spain.

The worst lot was that of stateless refugees, especially those (several dozen) in the Nanclares de Oca concentration camp. They ended up doing forced labor, under the somewhat fictitious sentence of not having obeyed the expulsion order: truly a blessing in an ugly disguise. Others ended up in a camp at Miranda de Ebro near Burgos that was basically a prefabricated prison.

Most were allowed to live in Barcelona and Madrid; there, they were supported by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, a Jewish humanitarian organization that paid for hotels and distributed money for their expenses. In the cities, they were given between 650 and 700 pesetas per person, with free maintenance, clothing and medical care.

As Avni points out, these amounts were very generous and allowed the refugees to lead a higher standard of living than the average Spanish government official. Indeed, my Spanish parents, who grew up in the following decade, were astonished to hear such amounts quoted: a peseta went a long way in the ruined Spain of 1943.

That year, the only American country with diplomatic representation in Paris was Argentina; after long negotiations, the Spanish government found that no one wanted to take charge of many undocumented European Jews, including the United States.

On March 6, 1943, meanwhile, Germany informed Madrid that it would only agree to the evacuation of Spanish subjects to Spain, never foreigners or stateless persons. By this time, the urgency of the situation was clear to many: as massacres of Jews became more widespread in occupied Europe from 1942 onwards, Spanish diplomats in various capitals began to encounter more and more cases of Jews seeking protection.

The situation was complicated even in North Africa, mostly distant from Nazi attentions. In Rabat, the Spanish consul Manuel del Moral, with the support of Lequerica, ambassador to Vichy, protected Spanish Jews in French territory by giving them papers; and both refused to persecute French and Moroccan Jews in the Spanish protectorate, as suggested by overzealous Vichy authorities, according to Lequerica in his correspondence from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

On March 7, 1942, Lequerica received clear and concise instructions from the ministry: “It’s your duty, within the norms and instructions that you have already received, to defend the interests of Spanish subjects of Sephardic origin by demanding compliance with the agreement of 1862” regarding the mutual protection of Spanish and French citizens.

In July 1942, Bernardo Rolland, the Spanish representative in Paris, stated in response to a question from Vichy’s Commissariat General aux Questions Juives (General Office for Jewish Issues): “Spanish law makes no discrimination among its citizens on the basis of their religion and, consequently, despite their Jewish religion, Spain considers the Sephardim to be Spaniards. For this reason, I would be grateful if the French authorities and occupation forces would have the consideration not to impose on them those laws applying to Jews.” Shortly thereafter, the secretary of the Spanish Chamber of Commerce in France, José de Olázaga, came to Madrid to receive instructions on the protection of the property of Spanish subjects, including a certain Gategno, a major silk manufacturer in Lyon.

On March 18, 1943, urged by Ambassador Ginés Vidal y Saura in Berlin, Foreign Minister Francisco Gómez-Jordana notified Rolland that visas would be granted to all Sephardim who could prove their Spanish status.

Hayes, the US ambassador in Madrid, recounts in his memoirs that on that same day Jordana sent Germán Baráibar, from the Directorate for Europe, to meet with American officials. The Spaniards explained that “the Spanish government wished to use its good offices to rescue as many Jews as possible from Nazi oppression and persecution and was willing to recognize an imaginary Spanish nationality for Sephardic Jews who were in German-occupied countries as a basis for requesting the German government to release these Jews and allow them to join the other refugees in Spain,” Avni writes.

This description is also found in a report that Hayes sent to Secretary of State Cordell Hull a year after this meeting: “This attests to the fact that the Spanish decided to save their subjects without Hayes’ influence,” Avni writes.

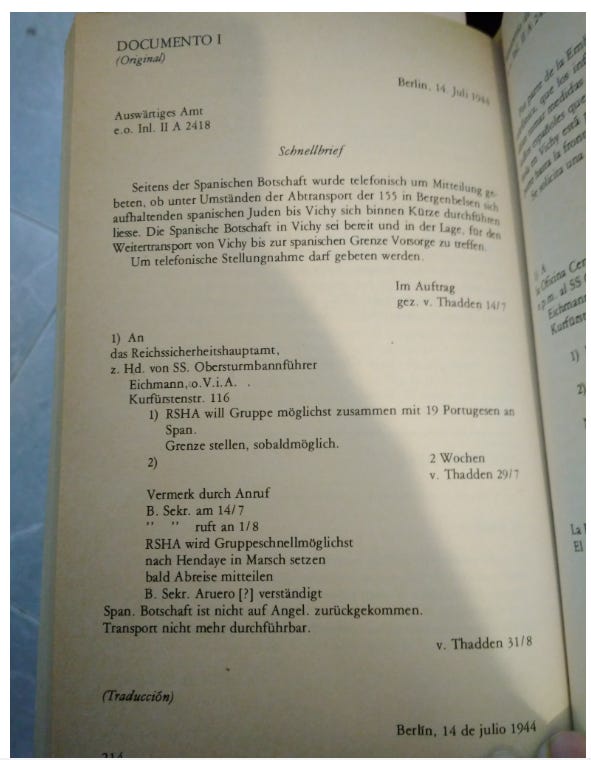

In his blog, the Spanish historian Pío Moa cites numerous documents on similar contacts and arrangements in 1944. One of them corresponds to a document that Avni published in his book; that year, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs addressed the Spanish ambassador in Bern:

I ask Your Excellency to request support from the German Government to obtain the transfer to Switzerland of a group of 150 Sephardim currently interned in Bergen-Belsen and provided with Spanish documentation and whose entry into Switzerland has already been, apparently, authorized by the Federal Police.

In this German-language document included in the appendix of Avni's book, German authorities notify their acceptance of the Spanish efforts to remove Spanish citizens from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp:

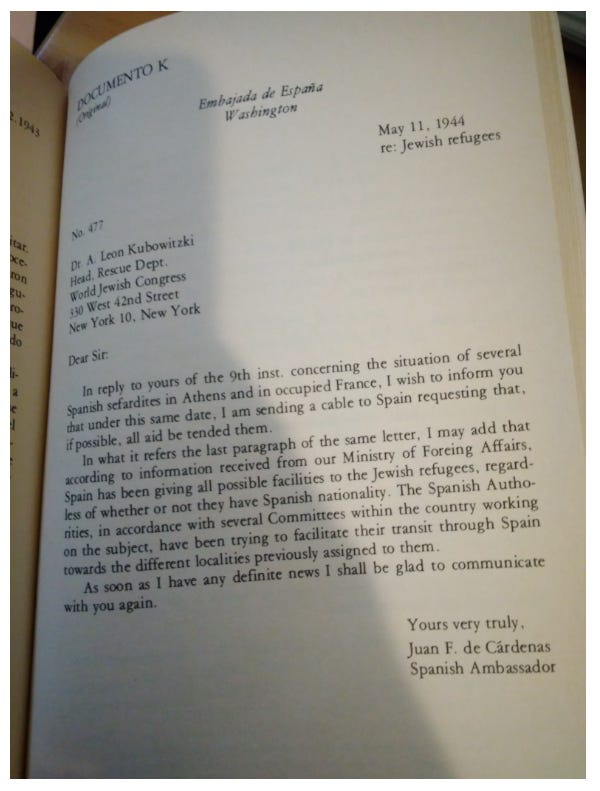

Meanwhile, the Spanish ambassador in Washington, Juan F. de Cárdenas, under pressure from Jewish communities to save threatened Jews in Europe, responded to one of such requests, in 1944, as follows (in English with a typo in the original):

I think it’s clear that the documentary evidence of the Spanish government's successful efforts to save tens of thousands of Jews from the Holocaust is overwhelming. Luis Suárez, in “Franco y su tiempo”, published in eight volumes in 1984 (in Spanish), includes more, for those who are not satisfied.

Just for context, I will add that Fascist Italy, until the dismissal of Benito Mussolini in 1943, was generally opposed to the radical anti-Semitism of the Nazis. It still was significantly more anti-Semitic than Franco's Spain, along the lines of minor Axis countries such as Bulgaria and Hungary.

In 1942, when Switzerland began to turn away Jews at the border and hand them over to the Germans en masse, the occupation of French departments by the Italian state offered another escape route, with Italian Fascists turning a blind eye to thousands who crossed into the area from Vichy territory.

The story did not end well. After Italy left the Axis, many of the thousands of Jews who had found refuge in Catholic Church buildings were deported to the camps in the East, and the Vatican failed to protest.

Portugal was another particular case, albeit one which I have not been able to study as closely as Spain’s. The US’ National Public Radio describes here the ordeal of Aristides de Sousa Mendes, the Portuguese consul in Bordeaux who allegedly gave out 30,000 visas to refugees fleeing occupied Germany — who presumably made into Portugal, quite obviously, via Spain.

De Sousa’s case is fairly complicated, but it seems clear that De Sousa was punished for having violated explicit orders to limit the issuance of visas, and suspended from the Portuguese diplomatic service. A similar fate awaited Hiram "Harry" Bingham IV, the American consul in Marseille in 1940, also punished in his country for having blithely granted visas to refugees; and the same happened to the famous Varian Fry, punished by Washington for his role in that city.

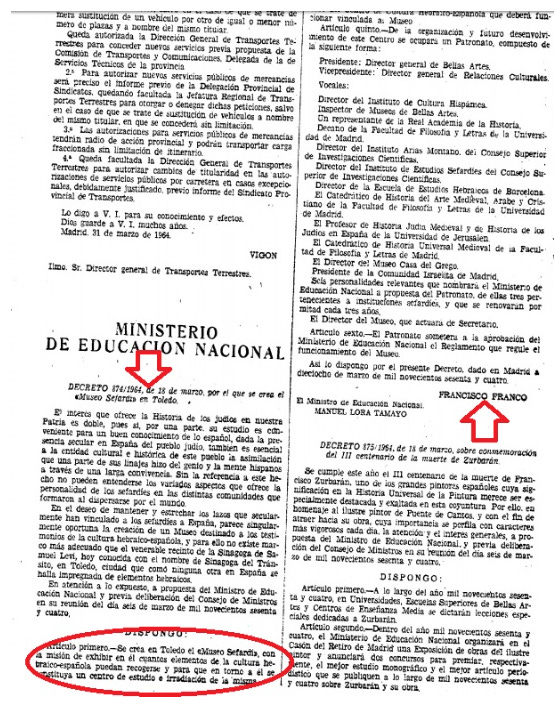

I don't know of a single case in which a Spanish diplomat was punished for helping refugees: the most famous of Franco’s little helpers, Angel Sanz Briz, ended his days as ambassador to the Vatican, one of the most prized positions in the diplomatic world, having been before the first Spanish ambassador to the People's Republic of China. In 1964, Spain opened its first Sephardic museum in Toledo.

One final note. Throughout his life, Sanz Briz credited Franco’s instructions and Christian concern for the fate of the Jews for the efforts made by him and other diplomats to save as many as they could from death and suffering. After Franco’s death, Sanz Briz’s family members found it convenient and in tune with the new times to claim that their famous relative had acted alone and even in defiance of Franco.

This, as I just showed, is so unbelievable as to be laughable, but remains the position of many. Sanz Briz’s family has maintained a degree of fame tending this particular legend with care, which helps to keep it alive. In the absence of evidence that contradicts all that which I just presented, anybody reasonable can only conclude that such is a not a serious position to hold, and certainly not one that deserves any more attention and commentary.

Israel later voted in favor of Spain’s entry into the UN in 1955, when Franco was already friends with the Americans.

Nicolás Valle, for long a foreign correspondent for Catalan’s public TV3, told me in a private conversation about several possible, and yet unconfirmed, names of Jews returned to Vichy that emerged in an investigation he conducted for his network. Avni wrote that “there is no exact information” on alleged expulsions to France, but it is believed, in the abstract, that there were some cases, without details, and in others the authorities were bribed to avoid expulsion. I have yet to read of a single case of expulsion identified by name.

These, and similar episodes, are recounted in “Human Smoke”, by Nicholson Baker.

God rest the soul of His servant, Francisco.

You might want to read “Three Popes and the Jews” which clears the air on Pius XII, who wasn’t protesting because he was actively saving in the words of the author 770,000 Jews , including thousands in Rome at the time of the not protested expulsions.

The author was Pinchas Lapide, Jewish Theologian and Israeli diplomat. He is in no way a cheerleader, he’s just defending the record. He was also a WW2 veteran.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Popes_and_the_Jews

I think personally a lot of this has to do with the church not getting in line on abortion, gay rights, and modern mores. To wit the American line will reliably be the Israeli line (not the other way round).