Quick Take: How Yugoslavia Was Murdered & Dismembered (2)

Final part of the history of how the West first attempted to crush Slavs who won't play ball

(The first part of this post is here.)

As military clashes spread across Yugoslavia in 1991, Croatia became a very particular case within a very particular country: it suddenly found itself with close to a third of the national territory under occupation by Serbs who lived there, descended from people who had lived there for centuries, and who wanted no part of the new Croatian state.

To nobody’s shock, the argument then put forward by Croatian diplomats was that boundaries between the Yugoslav republics were historically sanctioned, legal lines of division between sovereign entities that could not be adjusted under any circumstances whatsoever. If Croats wanted out of Yugoslavia, fine; if Serbs wanted out of Croatia, fuck them as hard as humanly possible.

This, of course, made little, let’s say, rational sense. As Nation points out (still p. 146), many people saw it at the time:

In fact, however, administrative expediency accounted for much of the logic of the Yugoslav republican boundaries drawn up after the Second World War, which were never intended to serve as state frontiers. There was some incongruity in an international legal regime that sanctioned the dismemberment of Yugoslavia itself, while simultaneously holding up its internal boundaries as inviolable. “The country’s external borders were made of cotton, its internal and regional frontiers of cement,” as one disillusioned critic (Slobodan Despot in the postface to Vjekoslav Radovic’s Spectres de la guerre: Chose vue par un Yougoslave privé de son pays, Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme, 1992, p. 216) put it.

The argument that internal borders separating Yugoslav republics were sacrosanct and the basis for all future arrangement was particularly beloved by the only Yugoslav republican leader during the wars of the 1990s without a Communist background, the Muslim Alija Izetbegovic.

The man was a walking and talking relic of the past: briefly imprisoned in 1946 for his opposition to Titoist policies toward Bosnia’s Muslim community, he later became a respected lawyer and leader of the political opposition. In 1983 he was tried, together with twelve associates, for a purported attempt to transform Bosnia-Herzegovina into an Islamic Republic, and sentenced to a 14-year term, only two years of which were served.

Izetbegovic was terrified of a possible arrangement between the two largest ethnicities of Yugoslavia, Serbs and Croats, to divide Bosnia between themselves. He wasn’t paranoid: Tudjman and Milosevic, two former Communists with similar interests and views, had met several times and, in March 1991, they had outlined a common strategy based upon the partition of Bosnia-Herzegovina by exchanging multiple chunks of land with hard-to-spell names, leaving a small Bosniak state in the middle, as a residue (p. 154):

Obsessed with his role in history, Tudjman kept a nearly complete file of recordings of confidential conversations with colleagues conducted in the presidential office. The portions of these tapes that have been made public reveal that the Croatian President repeatedly made reference to schemes for partitioning Bosnia-Herzegovina, notably in conversation with Mate Boban and Gojko Šušak on November 28, 1993, where he speaks of trading occupied areas along the Sava for territory in western Bosnia, and as late as April 1999, when Tudjman suggested exchanging the Prevlaka Peninsula and a point of access to the Adriatic to the Serbs in exchange for Banja Luka and the Bosanska Krajina.

In typical fashion, these revealing tapes have locally been described as “Croatia’s Watergate Tapes.” The existence of the tapes – a hoard of evidence showing that Tudjman was more willing to negotiate than his Western partners and backers – was revealed following the HDZ’s electoral defeat in 1999, but only small excerpts have been published.

The Tudjman family unsuccessfully sued to have the tapes returned; in the summer of 2002, under pressure to surrender the tapes to the International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia in The Hague, the Croatian government made the decision to restrict all access to the documents for a period of 30 years: surely because there’s nothing incriminating there.

You may be wondering why I care so much about the travails of wild peoples who murdered each other with so much abandon. After all, like I wrote before, this was mostly their fault. They had a little fire going on and all foreigners did was pour petrol on it. Yes, that didn’t help, but you definitely needed the fire to get the conflagration going.

I care because this was my first experience as a journalist. Like I wrote in part one, I was a journalism apprentice when I talked a few friends who were doing a dirt cheap Eurorail train trip with me, to stop by for a few days at Zagreb, Croatia. The war was still going on, a few kilometers to the east, but the city itself was not particularly dangerous: just full of refugees, jumpy locals and guys looking like mercenaries.

We just spent a few eventful hours in Zagreb. The kind owner of a establishment full of grizzled war veterans – who obviously were getting some rest before they were sent to the front – convinced us to take the first train to neighboring Slovenia, where there really was no war.

We ended up in a ramshackle, but pretty, beachfront hostel in Pula, a Croatian town close to Italy. The place was crammed with Croatian refugees from Mostar, an ethnically-divided Bosnian city where all sorts of horrors had occurred, before and after UN Spanish troops (members of so-called UNPROFOR forces patrolling Bosnian enclaves) had arrived to separate the contending Croat and Muslim minorities.

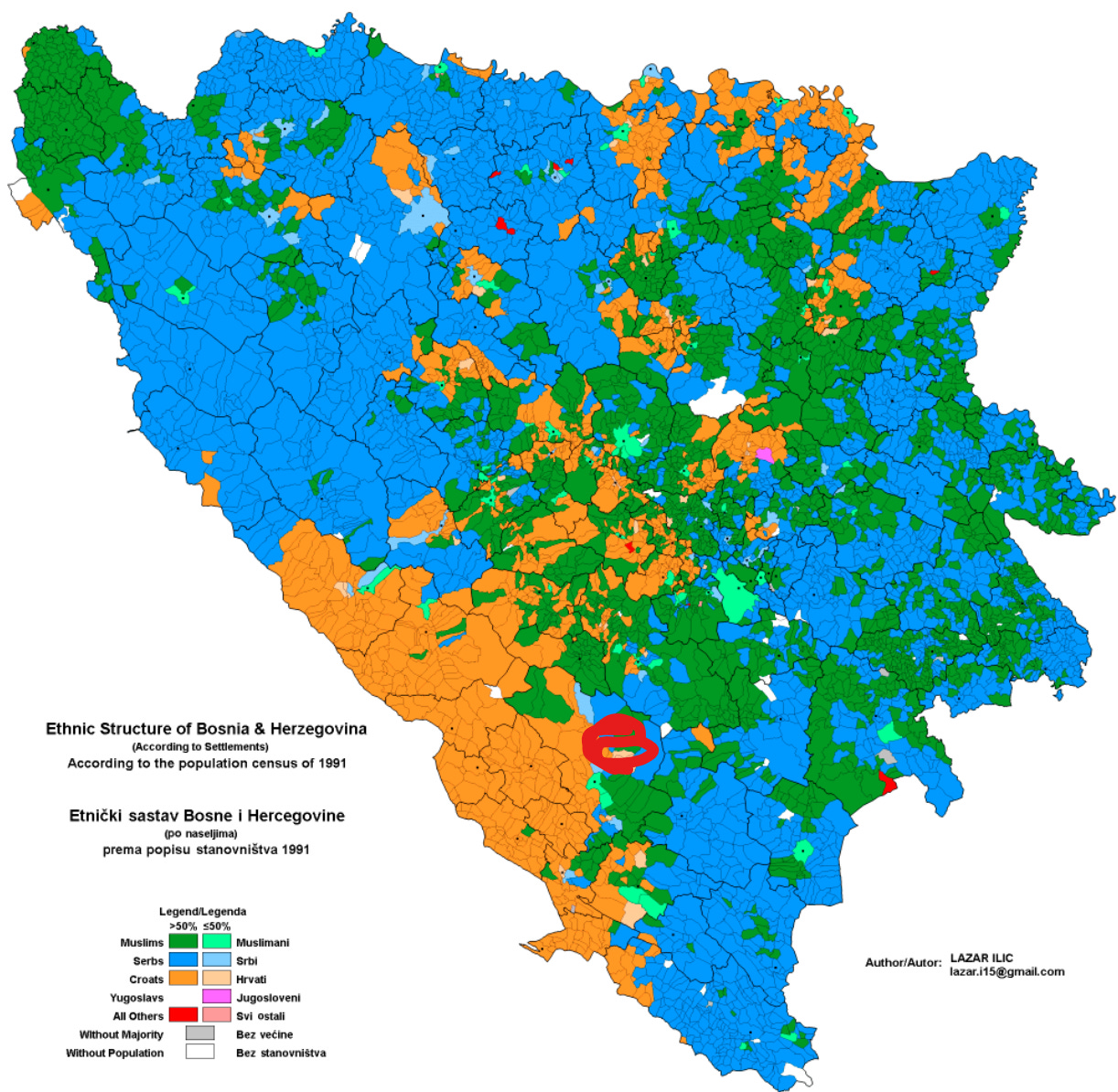

(Mostar: notice the minaret to the right. Croats — Catholics — live on the left bank of the river; Bosniaks — Muslims — on the right side. Mostar is the little red circle on the ethnic map of Bosnia, circa 1991, below:)

When the refugees learned that me and my friends were Spanish, well, that wasn’t pretty. We were all in our early 20s, short-haired, in reasonable shape: we looked a lot like UN soldiers on vacation, and some of the refugees didn’t believe us when we explained – through a helpful translator – that we weren’t.

One afternoon, as I was staring at the sea, bored, several of the refugees came close to physically attack me and a friend; luckily, the translator was nearby. The translator explained that these people had suffered much in Mostar and they blamed the Spanish soldiers, fairly or unfairly, for siding with the Muslims.

I understood then: on the train ride on the way down to Pula, I had sat down next to a young Croat who explained to me, in broken Borat-style English, that all Serbs are wild psychopaths and blood-thirsty monkeys. I understand even more now. Perhaps it wasn’t even the case that the refugees had personally been the victim of Bosniak violence: war propaganda, fueled in the West to portray the Serbs as monsters (with the Muslims as sidekick monsters in Croatia). In Yugoslavia itself, as Nation writes, it was overwhelming. This is from p. 147:

It quickly became clear that all parties to the conflict were in the business of using atrocity rumors instrumentally in order to win the sympathy of a wider audience. Sorting out fact from fiction in the volatile circumstances of armed conflict is never easy. In the Yugoslav case, where efforts to demonize the enemy became a strategy of war pursued by professional public relations firms such as Ruder Finn Global Public Affairs, the challenge was particularly severe.

In p. 156, Nation recalls a Serbian acquaintance of his, the widow of a former Yugoslav diplomat from Croatia and owner of a home in Split and flat in Belgrade, who reported viewing a news broadcast in Belgrade during the autumn of 1991, including graphic images of mutilated cadavers, described as the Serb victims of Croat terror:

Upon returning to Split, she viewed the identical images on Croatian television, with the cadavers described as the Croat victims of Chetnik (Serb) terror. Such abusive use of the pornography of death for political purposes, without regard to circumstance or fact, was widespread.

Widely publicized images of the picturesque touristic town of Dubrovnik under assault (“to some extent engineered by Croatian defenders who used the city’s medieval towers as gun placements and allegedly burnt piles of tires to create photogenic smoke effects for the international media”) were also used to good effect to convey the impression of a barbaric Serb invader (p. 158). I recall they were all over the news reports, all the time. People loved the burning tires of Dubrovnik, seen as clear-cut evidence of Serb criminal nature.

The bombing of the Croat presidential palace in the heart of Zagreb’s old city, an action devoid of any apparent strategic logic, likewise cast discredit upon government forces (also p. 158). The destruction in Vukovar was much more representative (and a real enough example of Serbian brutality), but the quiet Slavonian city lacked the media appeal of an international tourist resort or the national capital.

In the midst of this mess, UNPROFOR troops like the ones the Mostar refugees hated became a byword for mission creep (p. 189). They had extremely limited mandates at first, including the monitoring of cease fires and the like, but big, foreign dreams.

When UNPROFOR commander Phillippe Morillon of France was temporarily detained by outraged citizens demanding protection during a visit to the Bosniak enclave of Srebrenica on March 11, 1993, he took the personal initiative of declaring the city a UN “Safe Area.”

This meant that the whole UN now had, because of Morillon’s whim, responsibility to protect a thickly-populated town notorious among Serbs as a homebase for armed, murderous incursions by Muslim militias – including foreign jihadis that had been streaming into Bosnia for years, and would later form the backbone of European branches of Al Qaida1 and the Islamic State. In June, with UN approval, the designation was extended to Sarajevo, Gorazde, Srebrenica, Tuzla, Zepa, and Bihac, all Bosniak-controlled areas. Nation explains (still p. 189):

“Unfortunately, the term safe area was a euphemism, used to describe what were in fact encircled and indefensible enclaves, teeming with displaced persons and with a combined population of over 1.2 million. In direct contravention of the safe area concept, several of the enclaves were used by Muslim forces as sanctuaries for launching raids against Serb-held territories.”

By assuming responsibility for their protection, Nation concludes, “UNPROFOR had saddled itself with a responsibility it was not prepared to honor and extended its mandate to the breaking point.”

Here one would be justified to stop and wonder: well, yes, this is a review of Craig Nation’s book, and you came up with all these direct quotations discussing stuff few people ever discuss about the war in Yugoslavia. But, how can we tell that he’s not a looney Serb-lover who is twisting facts to benefit, say, his secret Serb girlfriend with an axe to grind?

I’ve put the same question to myself, but the truth is that the published literature about the conflict mostly agrees with Nation’s interpretations. The problem here is not one of scholarly consensus versus looney Serb-lover, is one of “well, this was a long time ago anyway and nobody cares,” which is the most common response I come across when I point these facts out.

Take the memoirs of the late Richard Holbrooke, the top U.S. negotiator in Yugoslavia. There, we can read a detailed account of the negotiations leading up to the Dayton Agreement, the 1995 deal that ended the Bosnian war after the NATO air bombing campaign.

He makes it clear that the Bosniaks were the most obstinate party to the talks, and came closest to blowing up the negotiations for peace in Bosnia, while Serbia’s Milosevic made the most dramatic concessions. Holbrooke’s biographer, George Packer, concurs in his 2019 book “Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century”:

Packer reveals that Holbrooke had all but given up towards the end of Dayton and it was Milosevic, desperate for a deal, who saved him by making last-minute concessions and selling out his Bosnian Serb allies.

Surprised? You shouldn’t be. In 1992, in very publicized talks, the Muslim Bosniak leader Izetbegovic had foiled an earlier attempt to a treaty in Bosnia. The so-called “Lisbon Agreement,” a tri-ethnic solution partitioning the country into cantons, had been brokered by Portuguese diplomat José Cutileiro on behalf of the Conference of Europe.

The Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats signed the federalization scheme in Lisbon but, as this article ponts out, after meeting in Sarajevo with U.S. Ambassador to Yugoslavia Warren Zimmerman, Izetbegovic reneged. He rightly concluded that time (and the U.S.) would deliver a better deal — even if it was only a slightly better deal.

“The Lisbon Agreement and the Dayton Accords are so similar,” observed Gordon Bardos, “the main difference is the death of over 100,000 people” between 1992 and 1995.

Does this ring a bell, Volodymyr Zelenski of the Ukraine? The whole “we have a decent deal, but we can get a slightly better one if a lot of people get killed before”?

As Nation notes (p. 191), the Vance-Owen Peace Plan of 1993 was another missed chance. Nobody was ecstatic about it, and yet the Bosniaks quickly saw that the argument that it rewarded “Serbian aggression” was much appreciated by the new U.S. administration led by Bill Clinton, then in the process of trying new toys:

The alternative offered by the Clinton administration, still in the process of defining its approach to the Bosnian problem and torn by conflicting motives, became known as “Lift and Strike” — lifting the arms embargo against the Muslim party in order to allow it to organize a more effective defence (a policy that demanded collaboration with Croatia to ensure access for arms transfers) and selective air strikes under NATO auspices to punish Serb violations.

In his memoir of the war (“Balkan Odyssey,” 1996), the British peace envoy David Owen lambasted what he called a U.S. policy of “lift and pray” as “outrageous” and a “nightmare” intended to sabotage the mediation effort in order to cater to domestic interest groups.

Nation (p. 199) provides a specific example of this policy: in February-March 1994, building on the momentum of a Serb withdrawal from the outskirts of Sarajevo (the result, in part, of a massive media campaign involving the likes of Susan Sontag), Western pressure achieved the reopening of Tuzla Airport, with Russian observers brought in to monitor compliance:

Though justified as a means to facilitate the delivery of humanitarian aid, the gesture also had strategic significance — Tuzla was a bastion of support for a unified, multinational Bosnia-Herzegovina, and it would eventually become the focus of the U.S. military presence in the region. On February 27, in line with the strategic reappraisal underway, two NATO aircraft shot down four Yugoslav Jastreb jet fighters that had trespassed the no-fly zone near Banja Luka. This was the first combat action undertaken by the Alliance since its establishment in 1949, and a harbinger of things to come.

The same points are repeated and amplified in intelligence cables transmitted by UNPROFOR Canadian peacekeepers, declassified in 2022 and reviewed here by The Grayzone. As they put it, “received wisdom dictates the Americans were concerned that Brussels’ leading role in negotiations would weaken Washington’s international prestige, and assist in the soon-to-be European Union emerging as an independent power bloc following the collapse of Communism,” but the reality is much worse:

“The UNPROFOR cables expose a much darker agenda at work. Washington wanted Yugoslavia reduced to rubble, and planned to bring the Serbs violently to heel by prolonging the war as long as possible. To the US, the Serbs were the ethnic group most determined to preserve the troublesome independent republic’s existence.”

And more: “These aims were very effectively served by Washington’s absolutist assistance to the Bosniaks. It was an article of faith in the Western mainstream at the time, and remains so today, that Serb intransigence in negotiations blocked the path to peace in Bosnia. Yet, the UNPROFOR cables make repeatedly clear this was not the case.”

By 1993, it was clear to Canadian peacekeepers that the US was encouraging Izetbegovic to provoke the Serbs into military escalation, so that the US could increase assistance to the Bosniaks and comprehensively defeat the Serbs. One cable explains: “Serious talks in Geneva will not occur as long as Izetbegovic believes that airstrikes will be flown against the Serbs. These airstrikes will greatly strengthen his position and likely make him less cooperative in negotiations.”

To support the Bosniaks, the US resorted — as the cables denounce — to its old tried-and-tested tactic of relying on jihadists. Same as in Afghanistan in the 1980s and 1990s and in Syria later, same as in Azerbaijan, jihadists had joined the fight of their own volition and DC policymakers observed that they could be used against the American enemy of the day, the Serbs. This is has been known for a long time, but it’s another of those things that many prefer to forget. The use of Mujahedeen also helped to set up false flag incidents in which they fired against or shelled Muslim civilians to blame the Serbs.

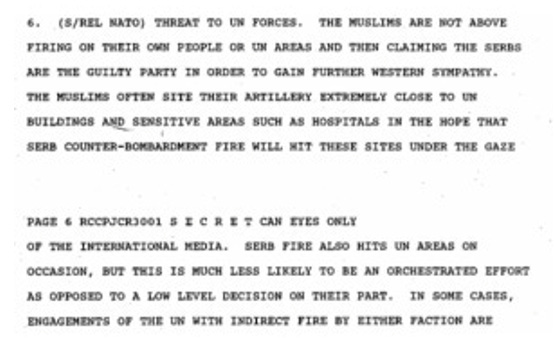

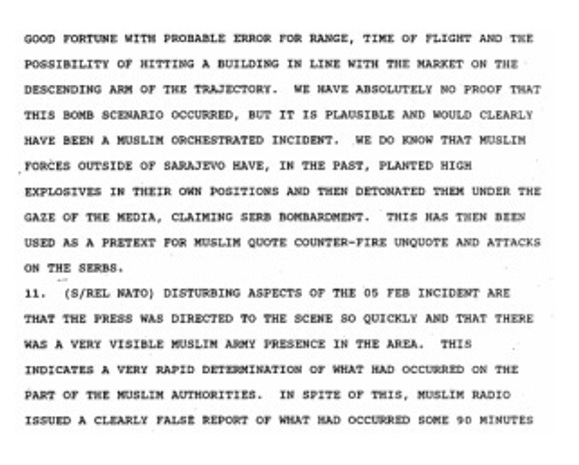

A particularly beloved tactic of the Bosniak side was triggering such false flag incidents in Sarajevo, in full view of international media: “We know that the Muslims have fired on their own civilians and the airfield in the past in order to gain media attention,” a memo concluded. A later memo observes, “Muslim forces outside of Sarajevo have, in the past, planted high explosives in their own positions and then detonated them under the gaze of the media, claiming Serb bombardment. This has then been used as a pretext for Muslim ‘counter-fire’ and attacks on the Serbs.”

Also, please note that a Serb general was convicted in 2003 by an international tribunal, as responsible for the massacre cited in this cable as a false flag incident.

I was in Colorado, working in a ski resort in Summit County, when Clinton finally found enough half-believable reasons to bomb the Serbs to shit, and ordered air strikes. The Croat army had been waiting for this for years. Within weeks, they broke a long ceasefire in Krajina (does it ring a bell now?), east of Zagreb, and expelled the entire Serb population from the region2. Centuries after it settled there, the entire Serb minority was ethnically removed. Not much later, Milosevic signed a deal to end all hostilities.

In 1999, the remaining rump of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) was again on the receiving end of Western rage. Amid increasing tensions in Muslim-majority Kovoso, a region within the supposedly inviolable boundaries of Yugoslav republics, the local Kosovar mafia reinforced its dominance over an increasingly lawless region. This 1987 New York Times report is clear evidence that this was a problem that long preceded the 1990s.

The Kosovar separatist movement was but a very thin fig-leaf covering an organized crime takeover, as Danilo Mandic wrote in his 2021 book “Gangsters and other statesmen: Mafias, separatists, and torn states in a globalized world.” In Kosovo, Mandic added, this mafia “assumed the role of a divider and ruler” during the turbulent 1990s and then during an insurrection that he describes as a “narco-funded armed liberation.” What was the West’s response to this? Belgrade was presented with the Rambouillet deal, a NATO plan that essentially represented a western takeover of the country.

This is, for example, the opinion of the brilliant Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek, who nobody will mistake for a Serbian apologist (he ran for Slovenian president in 1991, and remains remarkably anti-Serb and anti-Russian to this day). Zizek wrote thus about Rambouillet in “From Myth to Symptom – The Case of Kosovo” (2013):

At the Rambouillet negotiations early in the Spring of 1999, the Western proposal put Yugoslavia in an untenable position, effectively stripping it of its sovereignty. It demanded that NATO have free access to the military facilities in ALL of Yugoslavia – not just in Kosovo – the free use of all transport facilities, exemption from being prosecuted by Yugoslav authorities for any crimes committed, etc.etc. In short, an effective occupation of Yugoslavia. Does this not raise the suspicion that, at least for the USA, the Rambouillet meeting was from the very beginning not considered a serious negotiation? It raises the idea that perhaps the goal was from, the very beginning, to place Serbs in a position of having to reject the non-negotiable Western proposal, thus providing latitude for the bombing, by putting the blame on the Milošević’s “stubborn rejection of the peace proposal.”

This was the meeting in which the Kosovar Albanians – the West’s ostensible allies – showed up with such a unsophisticated negotiating team, basically a group of rural criminals out of The Godfather Part II, that its members mistook U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright for a cleaning lady (I also read this anecdote in the Spanish press at the time, although the correspondent falsely claimed it was the Serbs who made the mistake, obviously). Here’s Henry Kissinger, writing in The Daily Telegraph (1999) about the U.S. proposal presented during the event:

The Rambouillet text, which called on Serbia to admit NATO troops throughout Yugoslavia, was a provocation, an excuse to start bombing. Rambouillet is not a document that an angelic Serb could have accepted. It was a terrible diplomatic document that should never have been presented in that form.

About 2,000 Serbs were killed in NATO’s “surgical strikes” that often deliberately targeted civilians over the next few months. Over 200,000 Serbs were expelled from their homes in Kosovo, never to return. Kit Klarenberg recently summed up the greatest hits:

For 78 straight days, NATO relentlessly blitzed civilian, government, and industrial infrastructure throughout the country, killing untold innocent people - including children - and disrupting daily life for millions.

The purported purpose of this onslaught was to prevent a planned genocide of Kosovo’s Albanian population by Yugoslav forces. As a May 2000 British parliamentary committee concluded however, it was only after the bombing began that Belgrade began assaulting the province. Moreover, this effort was explicitly concerned with neutralising the CIA and MI6-backed Kosovo Liberation Army, an Al Qaeda-linked extremist group, not attacking Albanian citizens. Meanwhile, in September 2001, a UN court determined Yugoslavia’s actions in Kosovo were not genocidal in nature, or intent.

This Muslim veteran of the war told the British press that it was they, the Kosovo Liberation Army, who incentivized the Muslim population to leave Kosovo, to give credence to accusations of ethnic cleansing against Milosevic.

Within a few years, Montenegro was detached from Serbia after an independence referendum that surely ranks as one of the most corrupt and manipulated in history, led by a man seen as so corrupt by his own Western allies that he has his own webpage with links to all the international reports against him; when NATO wanted to absorb Montenegro, to rub it in even more, popular opposition was so widespread that the government refused to run a referendum and applied to join the organization merely after a vote in a parliament full of cronies and representatives from various mafias. Montenegro is a proud NATO member since 2017.

It’s worth having a quick look of any map of the former Yugoslavia, and find out the places where the population that was ethnically cleansed during the wars of 1991-99 has never been allowed back.

There are only two such regions: Krajina, the Serb-majority region east of Zagreb; and almost all of Kosovo, except for the northern enclaves around (parts of) Mitrovica, from where Serbs were pushed out in 1999 by the victorious, NATO-supported Albanians.

This makes perfect sense, considering that the number one driver for foreign (German-led) hostility to the continued existence of Yugoslavia was anti-Serbian sentiment. Serbia, Czarist Russia’s closest ally for decades and a key reason for a series of wars that led to Germany losing its dominant position in Europe, had to be punished, and it was. Russia’s ally had to be shown how things stand now that Russia won’t protect you anymore.

Throughout Bosnia, where Muslims and Croats were often cleansed by Serbs, hundreds of thousands have been allowed to return to their former homes. In the Serbian Republic (the Serbian region of Bosnia) there are well over 100,000 Muslim residents as of the last census of 2013, out of a population of scarcely over one million. In Sarajevo, the Bosniak capital, finding alcoholic drinks in hotels and restaurants is becoming harder every day.

Amer Azizi, one such veteran who later joined Al Qaida, remains the main suspect for the role of organizer of the Madrid bombings of 2004, the largest terror attack in European history: https://www.urjc.es/todas-las-noticias-de-actualidad/7235-fernando-reinares-premiado-por-la-asociacion-11-m-afectados-del-terrorismo. Practically nobody, and I mean nobody, knows this in Spain, because the fact has been carefully omitted from books and news reports for two decades now.

Serbs consistently represented well over 10% of Croatia’s population for centuries (17% of the population in 1900), and were 12% of the census in 1991; they are less than 5% now.

Thank you for sharing :)

November 21st , 1995;

Hanau, Germany- after several weeks at Graf/Hohenfels training for Bosnia, word came in the morning the Dayton accords had collapsed.

YAY 😀 🥳🎉 we were all home and drinking by noon.

1800~ local

☎️ ring…

Dude we gotta go into Brigade it’s on again

“Quit fucking with me”

Turn on the TV…

20:00 GMT +2 Ultimate Buzzkill Staff meeting…

(Why yes we had been drinking).

“S3 whaddya got?”

“Well Bob, I lost confidence in the whole thing when Division couldn’t contract a bus for advance party…”

Moods didn’t improve.

I slammed a phone down on a Major “Karen” later …

Before sending a borderline insubordinate fax response …

…. And off we went…

Pepperidge Farm remembers… 🤣