Quick Take: Let's Stop Comparing Baddies to Hitler

Let's stop comparing every evil dictator to Hitler: let's nip Elevatio ad Hitlerum in the bud

To subscribe, just click here; if you want paid access but the price is a little too steep for you right now, just email me (respond to this email) and we’ll sort something out.

History is a vast early warning system.

China’s Tang Dynasty ended up holding power for almost three centuries (618-907), becoming the country’s longest-lasting and most celebrated, although during its first few years it looked like it would go away fast. It was only saved because its second emperor, Li Shimin, was well versed in the history of early Chinese wars.

As a young general in command of the best Tang army, facing overwhelming odds against insurgents in 621, Li Shimin was an Alexander-style soldier famed for his bravery, horsemanship, and training in archery and swordplay. Many of his enemies were just as skilled in those arts as he was, but only he had an education in the Chinese classics to go with his military ability.

In the two-month Battle of Hulao that year, Li Shimin defeated the combined forces of two anti-Tang warlords, with at least three times his forces, by spicing up his defensive tactics with feints and well-timed cavalry assaults, and by displaying a capacity to lead from the front — particularly when the enemy was on the retreat.

Where did he learn that? At this juncture, Li Shimin relied on the work of two famous scholars: the description of a Han Dynasty battle by Sima Qian, a contemporary of Rome’s Gaius Marius; and Sun Tzu’s “Art of War,” with its central observation that troops that have nowhere to go fight harder (I’ve discussed Sun Tzu/Sun Wu before here):

“Throw them into a place from which there is nowhere to go, and they will die rather than flee. When they are facing death, how could one not obtain the utmost strength from the officers and men? When soldiers have fallen in deep, they have no sense of fear.”

It was because of these works that Li Shimin knew how and when to apply those tactics, how and when attack and retreat so that a superior enemy could be beaten. That’s how you use history to your advantage, that’s how you use it as an early warning system.

The broader West has as long a literary and historical tradition as China but this tradition is not, regrettably, quite as deep. In China, when the scheming eunuch Zhao Gao told everyone in a 3rd century BC imperial court that a deer was a horse, courtesans (and later historians) understood that he was conducting a test of loyalty — he was ascertaining who would be willing to cave and accept his word that day was night and night was day, and who wouldn’t: so he would know who his useful toadies were, on one side, and his enemies were, on the other.

Emperor Whisperers: Point Deer Make Horse

Welcome! I'm David Roman and this is my History of Mankind newsletter. If you've received it, then you either subscribed or someone kind and decent forwarded it to you. If you fit into the latter camp and want to subscribe, then you can click on this little button below:

When the Roman emperor Caligula did the same in a Roman court in the First Century AD — by announcing that he intended to make his horse Incitatus a priest, and later a consul — this was taken not as evidence that Caligula was testing loyalties, but as evidence of madness, both by contemporaries and later historians who didn’t understand the move.

To this day, every educated Chinese person knows the saying about Zhao Gao, summed up as “point to a deer, turn it into a horse,” 指鹿為馬 (“zhi lu wei ma”). In the West, what educated people know about Caligula, to summarize, is that he was a crazy man.

This is why I get upset with comparisons between Adolf Hitler and the Nazis on one side, and whoever is the designated enemy of the West on the other. Because we Westerners seem to have an extremely narrow frame of reference, for a culture with such a huge history.

For the longest time, Saddam Hussein wasn’t the bloodthirsty president-for-life of a ramshackle fourth-rate power — he was the next Hitler, who had to be stopped in his tracks before he could trigger another world war; so was the Serbian Slobodan Milosevic; and so was Kim Il-Sung, president of North Korea.

In every case, those who urged caution when the US bombed Serbia or invaded Iraq in 2003 or every time Israel’s Bibi Netanyahu calls for a large-scale war to destroy the Iranian regime were the new “appeasers” who had given Hitler Czechoslovakia in 1938.

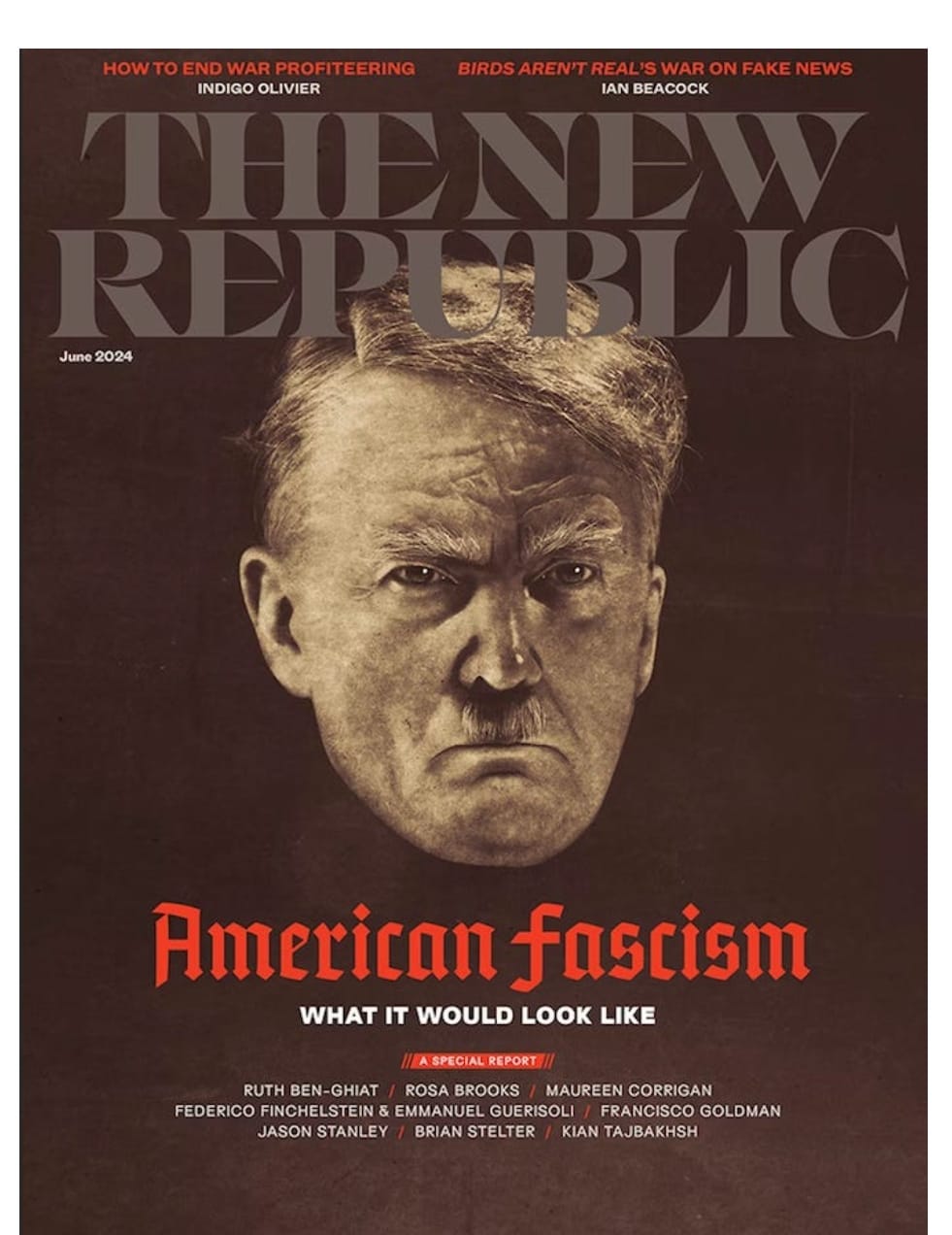

And so it goes: Donald Trump is routinely compared to Hitler or described as “literally Hitler” and the comparisons between Vladimir Putin and Russia in 2022-2024 and Hitler and Nazi Germany in 1938-1939 are so commonplace that entire books could be written about them. And everyone who is even mildly concerned with triggering World War III is an “appeaser” like that alleged slug of a British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, the villain of 1938 — even though Neville Chamberlain was the hero & winner in the talks with Hitler that delayed WWII for a year.

Of course, we all know that this kind of rhetoric surely has nothing to do with the fact that two people have now attempted to kill Baby Hitler Trump before he can win another election.

Look, I love historical comparisons. I think they’re great and can be really useful, like they were for Li Shimin in 621, like they are for any Chinese office drone who, as we speak, is being told by his boss that day is night and his remembering the deer and the horse, and passing the test of loyalty.

I recently published a short essay comparing Donald Trump to an ancient Roman politician named Caecus. I didn’t compare him to Hitler not just because I don’t think that there’s absolutely any point in common between an Austrian who would send scientists to the gas chambers because they were Jews, and a guy from New York who gave Jared Freaking Kushner a high-profile job in his administration.

I mostly looked for a different historical person to compare Trump to because I don’t want to be lazy and become the one-millionth newsletter writer to make the Hitler comparison.

This is not about “Reductio Ad Hitlerum” arguments. This idea was best expressed by Leo Strauss as “a view is not refuted by the fact that it happens to have been shared by Hitler,” and you probably are aware that Hitler was, at least for a while, a vegetarian who abhorred tobacco. Reductio ad Hitlerum arguments are doubly reductionist because they almost always happen at the end of long discussions, when many other arguments have been exhausted, and the bright comeback appears in the mind of whoever is losing: that thing you are proposing, the desperate final retort goes, that thing is Hitler-like.

What I’m most concerned about, the thing I’m advocating against here, goes beyond Reductio ad Hitlerum because the argument is not presented as a last recourse, but as front, center and headline: such and such is Hitler, such and such idea is Nazi-like. Sticking to Latin, perhaps a better definition for what I’m objecting to is “Elevatio ad Hitlerum”: to make every perceived threat or enemy rise to the level of Nazi-like evil and danger.

In a recent exchange we had in Notes,

objected to my objection with what I think is the best possible argument: that, yes, citing Hitler all the freaking time is simplistic and very often misleading (at least as to the degree of the actual threat one is calling attention to) but it’s also effective. He’s right.I myself have often — like everyone else — compared specific pressure points in contemporary politics to well-known milestones of Nazi Germany. I understand the usefulness of these comparisons, because pretty much everyone knows something about the Nazis and few people know much about Li Shimin and Zhao Gao outside of China.

That’s why I don’t think we will ever get rid of the Reductio ad Hitlerum. Eventually, if you discuss a thorny geopolitical issue long enough, either you or somebody else will bring up the Nazis. It’s in part lazy, yes, but it’s also convenient, because Nazi Germany, for better or worse, is for many of us a, let’s say, area of shared expertise (I even wrote a novel about Nazi Germany, for crying out loud).

Reductio ad Hitlerum is like smoking: definitely bad for you in the long-term, to be avoided, but fairly innocuous if you just quit soon; Elevatio ad Hitlerum is like alcoholism: it doesn’t really have any bright side, it doesn’t help you look cool, it’s destructive from day one, and it will wreck your mind even as you think you’re just having a laugh or two.

I do think we can get rid of Elevatio ad Hitlerum. Let’s not start the argument with “the Myanmar Junta is just like the Nazis” or “that guy who may become Primer Minister of Moldavia is just like Hitler.” Let’s try something else, at least at first. Let’s keep digging into on our shared Western heritage to find better comparisons, at least to start with.

As a fan of Roman History, I would compare Trump to Tiberius Gracchus. Very different political goals, but Gracchus did destabilize the political process of the Republic that had worked relatively well for centuries, he broke precedent by running for a second term as Tribune, he had little hesitation in breaking political norms and traditions; for example deposing a tribune who vetoed his legislation using intimidation and violence in the process, he had a cult like following with segments of the population, and the political process did descend into violence between his supporters and the Senate.

Ofcourse he came no where close to toppling the Republic, the allegations made by his enemies of him wanting to be king were obviously false.

But ominously he set in process the motion of political decay, the decline of institutions, leading to decades of competition between political strongmen and generals, eventually leading to rule by the Emperors about a century later.

Orban was a Hitler for a while there, because he wasn’t fully onboard with all the western agenda.