Quick Take: Political Unification Has Turned Europe Into a Substandard Version of China

Europe's killer app was political fragmentation and now it's gone, so Europe sucks

Being European by birth, I find the continent’s descent into powerlessness and irrelevance over the last few decades rather worrisome. The attempt to create a United States of Europe has left us with a sclerotic, bureaucratic super-state that has all the worst attributes of imperial China without any of its advantages.

It’s an old joke that the European Union is a 1970s solution to a 1940s problem, and yet the joke has never been more real. I could spend all day citing horrible data points illustrating the EU’s utter economic, demographic, moral and cultural collapse: I will simply point to the fact that, in 2008, the eurozone’s GDP was the same as the US, while in 2023 was almost half of the US’. Europe’s three largest companies, by this order, make their money by selling diet pills, overpriced French fashion accessories and the worst corporate software ever invented (yeah, I’ve used your pathetic software for years, SAP, yeah I know you by your deeds).

This makes sense: after all, the EU was created to solve a problem that Henry Kissinger popularized in that great decade of the 1970s: when he wanted something done in Western Europe, he complained, there was nobody to call. Now there is! After all, when in history has a vassal surpassed its master in any sense, in any industry or endeavor. Never. The most the vassal can aspire to is that the master gets distracted and tries to nab Gaza instead of Greenland.

I spent some time covering the EU institutions in Brussels, which is one of the world’s most dispiriting places and boasts a unique concentration of unappealing, useless and arrogant people, whose main skill is a certain ability to combine powerlessness with bigotry (real bigotry). If Washington DC is Hollywood for the ugly, Brussels is Washington for the bureaucratic underclass, the poor ugliest Ozempic-swallowing losers who couldn’t make it in Washington.

That Brussels has become Europe’s top power center says it all about the continent’s decadence. A backwater of zero interest to anyone throughout history, in the 19th century became the capital city of the new country of Belgium because the Netherlands’ Catholics couldn’t stand the typically smug Protestant elite of Holland; and by the next century the country that only came to exist to protect Catholicism became militantly atheistic, with a capital carefully divided between French and Dutch districts that is filled with Muslims mostly of African extraction1.

It really is shocking to see Europe in such a state because, for a long time, it was China that was the go-to example of an ossified system that lost all capacity to innovate and adapt.

For just over a millennium, the Chinese embarked in an extraordinary process of technological and social advancement that gave us not only the usual suspects like decimal multiplication tables, toilet paper, gunpowder, horse collars, firearms, explosive bombs, moveable type and the magnetic compass, but also the invention of new ideas and concepts.

For example, Communism was actually invented by the Chinese of this era, twice. First, it was Wang Mang, who briefly seized power from the Han with a revolutionary program that included land confiscation, the suppression of most private property, as well as establishing state monopolies on most commodities, and banning private ownership of gold. Wang Anshí came second, around a thousand years later under the Northern Song dynasty: he served as counsellor for the frustrated war-loving emperor Shenzong, whom he provided with funds by nationalizing pretty much everything and setting price-fixing mechanisms.

All this vibrant dynamic intellectual and technological activity was the logical consequence of a high-IQ, highly-educated populace with time and resources to innovate, and with the right incentives: many of the top Chinese inventions were developed at times of chaos and disunion, of war between Chinese states.

This virtuous process later ground to a halt: even as the Chinese grew in number and remained just as a smart and just as fond of education, China became an intellectual backwater, especially in terms of technology. Look around yourself: pretty much everything modern you see was invented by Europeans, in Europe or its overseas possessions, dependencies, extension packs and colonies, from computers to combustion engines, from bathrooms to T-shirts and bicycles.

The question of why Europe dominated the world to such an extent even as Europeans were, perhaps, a mere 20% of the global population and fought each other all the freaking time too, has left us with hundreds if not thousands of books. The response is probably a complex combination of factors, but this debate is much easier to grasp if we focus strictly on the comparison with China.

Like Europe, China is a temperate territory with ancient civilizations, multiple religions and a long history of civilized life. The biggest, perhaps the only, significant difference between China and Europe since about the year 1200 is a political one: China ever since has been a centralized state with a single center of power at almost all times, with only short exceptions. Whenever the Chinese center deemed a new technology or idea too dangerous or unnecessary, it would suppress it.

Cautionary examples of this kind of trend abound in Chinese history: from the very First Emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi, ordering a culling of ancient books as soon as he took the throne, to admiral Zheng He being ordered to destroy the fleet he had used to successfully explore the Indian Ocean in the early 15th century, to the last great Chinese emperor, Qianlong, and his efforts to destroy all deviating thought in his realm.

Qianlong, the most recent of these examples, is perhaps the most striking. A brilliant strategist and successful ruler who spent six decades on the throne and died in 1799, he incorporated the Eastern Turkestan to China and crushed the Mongol threat for ever by creating the still-existing province of Inner Mongolia, well beyond the Great Wall.

In the manner of most Chinese emperors, Qianlong fancied himself a patron of the arts and aesthete. His summer retreat residence in Chengde, which I’ve visited, is larger and grander than most palaces ever built. Even though it was of secondary importance to his main residences in and outside Beijing, it’s so vast that it has small lodges so that the Emperor and his entourage could spend the night outside in the enclosed forests while hunting.

However, Qianlong’s reign was also marked by an ambitious attempt to censor the entire Chinese culture with the Siku Quanshu collection, including every book that was acceptable to Qianlong’s inclinations – and calling for the destruction of everything left outside. I don’t need to explain how bad this was for Chinese culture.

At the same time, Qianlong’s extremely centralized policy-making system was a disservice to China in 1793. That year, the self-styled United Kingdom sent its first embassy ever to China, under George Macartney, an arrogant toff who would have made a perfect EU commissioner (think of Chris Patten, but with actual power). After the British ambassador got involved in a highly-charged row over the proper ways to kowtow to a Chinese emperor, Qing policy would turn extremely hostile and disdainful to the world’s emerging superpower — with disastrous results including humiliating defeats, the imposition of drug liberalization policies, partial invasion and the loss of sovereignty as well as territories such as Hong Kong.

Throughout history, the cycle of Chinese unification-ossification-division-unification again has made it clear that advancements tend to come in precious times when political division exists. Innovation thrived when China didn’t have a single center of power, but competing ones, with various dynasties vying for power or multiple warlords controlling separate provinces. For example, almost all of what we know as Chinese philosophy was created during the Warring States period that came to a close with Qing Shi Huangdi’s book burning.

Political division was the secret ingredient to China’s inventions and advancements. It’s no wonder then that Europe, always more divided than China ever was2, with dozens of competing and hostile states and ethnicities, eventually surpassed China in terms of technology and the development of new ideas — in a process that started precisely in the 11th century, when Europe was so fragmented even within states that the king of France was barely more than an uppity aristocrat.

This is an idea that has permeated the contemporary Chinese political discourse. In his controversial book “Chinese History Revisited” (2009), historian Xiao Jiansheng argued that the relatively weak Song Dynasty — ruling a divided China before the Mongol invasion — represented a pinnacle in the history of Chinese civilization.

Xiao, in fact, maintained that the Song’s flourishing culture supported a benevolent government and open pluralistic society that enjoyed an unprecedented and robust commodity economy and material culture, precisely because it was politically weak. Xiao in fact framed the Song Dynasty as prime evidence to support his larger premise that Chinese civilization, as opposed to Chinese imperialism, has fared better during periods of political disunion than under its great centralizers and empire builders – a thesis with obvious contemporary implications.

In China under the last dynasty, the Qing, iconoclastic thinkers who wouldn’t listen were jailed or murdered. In medieval, Renaissance and modern Europe, such types, from Dante to Gutenberg to Descartes, Voltaire and Goya, went from court to court, looking for the protection of rulers who were often in conflict with their previous master.

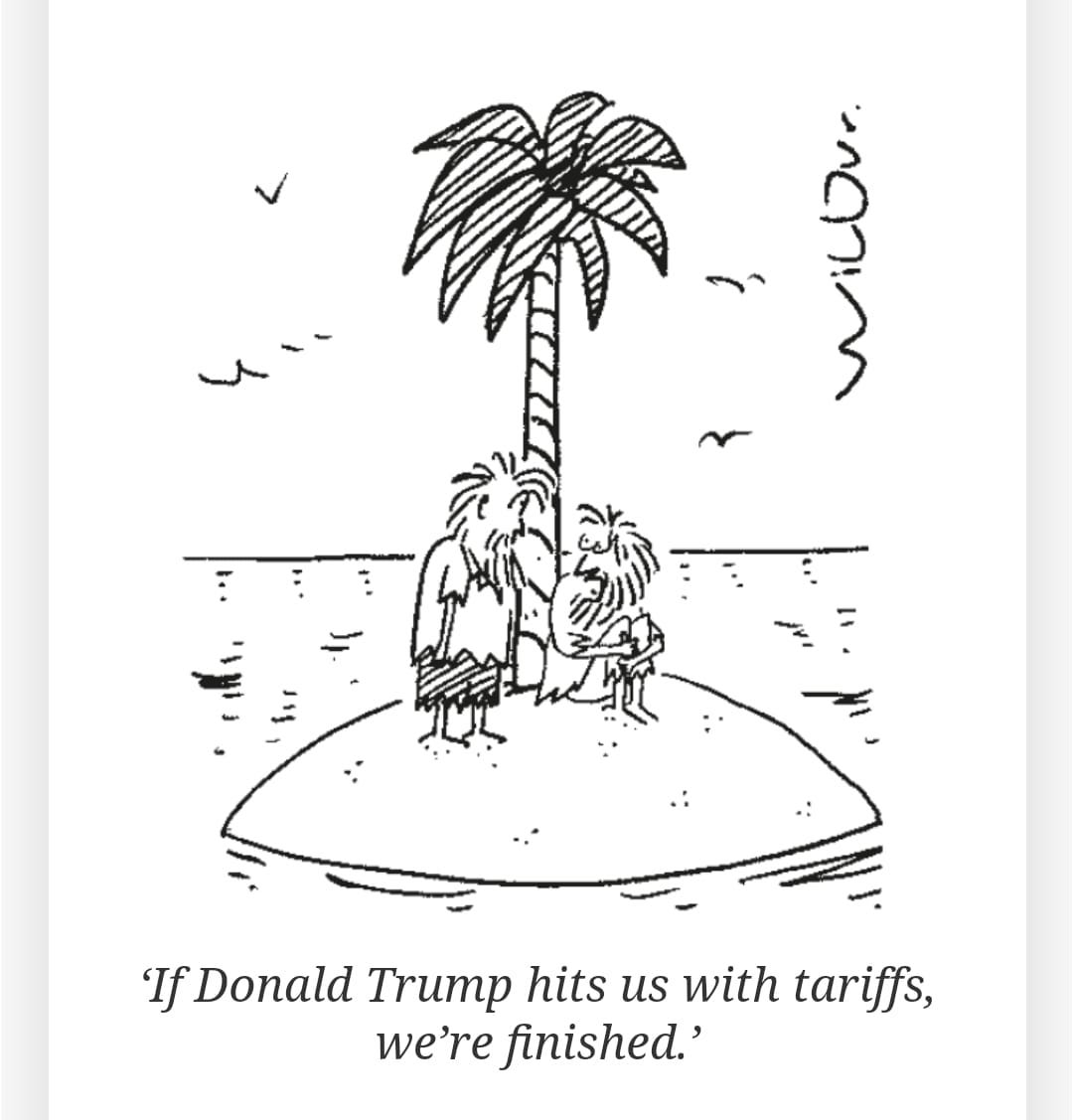

You lose political division, and you lose the chance of exile for dissidents, the possibility of trying things in a different way, of testing various approaches instead of a one-size-fits-all approved in Brussels. You get stuck with dunces like this one proclaiming themselves arbiters of truth for all. And, in Europe, you don’t even get imperialism, the other side of the centralizing deal in China: the EU is particularly useless when it comes to protecting its borders, projecting any sort of power or even producing ammo for its supposed allies.

One would think that this would be clear after decades of EU decline. And yet every day brings new evidence, a new imbecilic idea from the EU bureaucracy, from bans on fracking to mandatory approval of browsing cookies, from regulations on the shape of bananas to Stalinist crackdowns on “disinformation.”

If you want to understand how the minds of these bureaucrats work, you need to go back to their formative years of the 1990s, and the most brilliant TV show of the era. I’m talking, of course, of Beavis & Butthead.

In the “Meet God” episode, the two idiots are hitch-hiking by an empty road, within sight of another road, which is full of traffic; after several hours of waiting under the sun, Butthead— the one who always comes up with ideas — turns to Beavis, having found the root of the problem, and asks, in the same tone that exasperated eurocrats use when they notice their ideas have been mocked by reality:

“Are you moving your thumb?”

Belgium “is a great flat damp grim meadow speckled with church spires like pepper-boxes and dwellings like over-coloured baby-houses,” as you can read in “The letters of Wilkie Collins.”

It’s worth noting that, under the Roman empire, much of Europe was unified and, in fact, very much ossified in terms of technological advancement, as innovation slowed down dramatically and later came to a halt after the Hellenic era (a great time for political division and the peak of Greek achievements) and only resumed in the late Middle Ages, when soap was invented, for example. Here’s a short interview with a Stanford scholar who is making the case that the fall of Rome was actually very positive for Europe, as it led to heightened inter-state competition.

When my wife worked for a few months in Brussels in 2015, I got into a lift in a parking garage and it had 4 or 5 different bodily fluids on the floor. That pretty much summed up our stay in that cesspool.

One advantage of our European system is I can go on the countryside here in Austria and most homes have a rifle, animals, crops, and the know-how to get by. Can’t measure that with GDP. And behind the former iron curtain is a lot of that same independence and loathing for the EU.

Buen artículo. El año pasado por estas fechas visité por turismo Europa con mis hijos. No encontramos más europeos que musulmanes, negros y latinos. Una estafa si uno hace el esfuerzo de conocer Europa desde Latinoamérica. Europa se ve definitivamente mejor en los libros.