Quick Take: the Mystery of Australia's Aboriginals

The Aboriginals may be the strangest people who ever lived on Earth, and we don't know the half of it

To subscribe, just click here; if you want paid access to the full History of Mankind series but the price is a little too steep for you right now, just email me (respond to this email) and we’ll sort something out.

One of the reasons why I write quick takes like this one (or the one about Muslim propagandists taking credit for saving Graeco-Roman culture) is to hear from non-paying readers who may know a lot about a specific subject and would be interested to share their expertise, by commenting on or responding to my pieces.

Honestly, I really hope to hear from readers with ideas and suggestions for further reading on the topic of Aboriginal Australians, because I’ve been studying the subject for years and I believe I’m a bit stuck.

Mind you, I used to live in Australia, so I have actually come across Aboriginals. I’ve walked through their ancestral lands (even pubs in Sydney’s red light district count, I believe) and watched some of the sights their ancestors used to gaze at. I’ve read books and academic papers and essays, articles and reflections on the culture and history of Aboriginals. I’m still uncertain that I’m on the right track regarding the subject.

This is what I know about the history of the Aboriginals, in a nutshell, before first contact with the Europeans:

The huge, rugged island of New Guinea — hotly contested by multiple tribes of various ethnicities, many living in high altitude valleys where they probably didn’t have knowledge of the existence of the sea — was quite isolated from the rest of the planet. It remained so, generally speaking, for a far longer time than Sulawesi and the smaller islands to the east and south.

Still, this isolation was nothing compared with that of the continental mass of Australia. To the south of both Sulawesi and New Guinea, Australia might as well have been in another planet altogether, as far as most native Australians, Aboriginals1, were concerned.

The whole fauna of Australia evolved separately from that of other landmasses, with marsupials staying dominant over placentals and occupying most ecological niches. The arrival of the dingo, a kind of dog likely imported into Australia from New Guinea through the scarcely traveled Torres Strait, in around 2000 BC represented a small revolution with various impacts on the local fauna and Aboriginals.

Dingoes, smart and aggressive, soon specialized in hunting kangaroos and may have triggered the extinction of the Marsupial carnivores that survived the first tens of thousands of years of human presence, like the thylacine and the Tasmanian devil, as well as those of several more flightless bird species. Moreover, dingoes, like other dogs, easily came into symbiosis with humans and may have in fact been brought into the continent as human helpers.

Regardless, humans almost certainly had expanded all across Australia by the early 1st millennium AD, starting from the northwest and sweeping southwards and eastwards. The process wasn’t quick: even in the wettest, warmest millennia after the glacial period of the Younger Dryas ended with a rapid global warming burst in 9600 BC, most of the huge Australian land was a somewhat dry steppe with clusters of vegetation around massive, albeit superficial and seasonal, wetlands like those now known as the Lake Eyre basin.

At the same time, a steady cooling process meant that conditions in Australia by the 2nd millennium BC weren’t all that different from those in the 21st century, with large deserts and marginal bushlands taking up around 80% of the entire surface. Warmer and wetter conditions described in Eurasia as the Roman Warm Period were reflected in the rebirth of wetlands, although cooling again struck from the 4th and 5th century AD.

The global droughts related in Europe with the Justinian Plague era may have led to famines and a population decrease among Aboriginals, most of whom were accustomed to a nomadic life that implied a scarce availability of food surpluses for lean years. The effects of other climate events, like irregular El Niño and la Niña Southern Oscillations, sometimes associated with alternating periods of drought and floods particularly damaging for the thin, old, non-renewed red soil covering much of central Australia2, are hard to discern. They have certainly made Uluru, or Ayers Rock in the dark red center of the continent, one of the most spectacular exposed rocks on the planet.

Lacking any access to outside technologies and mostly living in ignorance that any sort of “outside” existed at all – particularly after rising sea levels separated mainland Australia from New Guinea in 6000 BC – Aboriginals for millennia relied on extremely primitive tools to survive in harsh environments and protect themselves against aggressive animals including carnivore kangaroos – Ekaltadeta, Procoptodon Goliah and related species – that eventually went extinct well before the Younger Dryas.

The fact that almost all aboriginal languages, except for a group clustered around the northwest edge of the continent where arrivals from other lands across the Wallace Line typically settled, belong to the same group – Pama-Nyungan, a family unrelated to any other language that dates back at least 70,000 years – is significant. It indicates that a reason for the relatively slow peopling of Australia is that a large majority of aboriginal tribes descended from a very small group of settlers.

Aboriginals are among the populations genetically more different from Sub-Saharan Africans, only surpassed in this regard by Native Americans. Paradoxically, African pygmies and Bushmen are genetically most different from Aboriginals, although occupying a similar hunter-gatherer niche3.

Aboriginals were very fast to explore their continent, and perhaps spread all over it within about 5,000 years4; they had already arrived in Tasmania, possibly taking advantage of a glacial-era land-bridge, around 40,000 BC. There, living in a cold but fairly fertile island with ample resources of every kind, they may have never grown much beyond 4,000 people divided in various warring clans – in fact, clannish warfare may have combined with glacial spells particularly acute so far south to keep the Tasmania’s population at very low levels for millennia.

Overall, the number of Australian Aboriginals may have never surpassed a million and was at around 750,000 in 17885, implying the lowest rate of natural growth of any isolated human group anywhere outside of very small islands.

This is such an extremely low rate of reproduction that it requires a REALLY CONVINCING explanation that I lack. It’s mind-boggling that even a small number of humans came across a freaking empty continent and they didn’t even grow to one million people after tens of thousands of years. This is so strange that it directly contradicts all available evidence about all human colonization processes anywhere else in the planet, with no exceptions that I know of.

The thing is: I have no idea why Aboriginals bred at such low rates, and I’m not sure anyone knows. It’s remarkable that many Australian marsupial species tend to have low rates of reproduction, adjustable during plentiful times. Aboriginals may have evolved similar approaches, albeit on a cultural rather than genetic basis. Have they? Has anyone studied this? Are we sure about the non-genetic part? I haven’t found evidence of it.

We do know that genetic and social evolution functioned in often puzzling ways in Australia. Aboriginals evolved genetic mutations that helped them survived the extremes of heat of cold that are characteristic of much of Australia – possibly a reason why they had less of an incentive to become very adept at sewing clothes for building shelters. At the same time, carnivore kangaroos and other dangerous animals and parasites may have limited population growth in ways that helped to create mythologies not unlike those of Sub-Saharan Africa, dominated by taboos, mysterious forces and witchcraft acting over the unwary. These myths didn’t stop pretty normal growth rates for Sub-Saharan populations over history, though.

African Gods Vs European Gods

Welcome! I'm David Roman and this is my History of Mankind newsletter. If you've received it, then you either subscribed or someone kind and decent forwarded it to you.

Aboriginals weren’t very able farmers, possibly because they lost farming traditions while crossing the mostly unfertile continent: most tribes outside of the Murray-Darling River System basin, the only of any significant length in all of Australia, may have never farmed. They instead maintained a hunter-gatherer mode of living that, while similar to that of South African tribes of the Kalahari Desert, was still rather backward compared with that of East Pacific societies that did have access to a slow but somewhat steady drip of outside technologies.

One important point to note is that Australia contains vast swathes of land that have never been desert-like at all, both on the western and eastern coasts, and some that have high-elevation mountain climates. The Kimberley region in the northwest, possibly the first to be settled, is dry and rugged and contains many well-watered patches. The Kakadu wetlands directly to the east of the Kimberley are hard to distinguish from the rainforests of New Guinea, and the same can be said for the very wet region of the Cape York Peninsula, full of savannahs and tropical rainforests6.

Still, aboriginals there didn’t develop toolkits or modes of social organization that were particularly different from the tribes that lived in semi-arid bushlands and the deep desert, and those who settled across the jungle lands in the north.

Like early Natufians in the Western Asian Levant, Aboriginals did develop a deep knowledge of their environment and the ability to influence it by favoring specific plants and landscapes over others. In fact, they had – like humans the world over – a massive effect on that environment, using fires to clear the land and produce fresh grass to attract large game, to keep paths open and to promote the growth of edible plants; in the process, they created, particularly along the eastern and southern seaboards, a pleasant countryside dominated by open woodland and much appreciated by European settlers who took it over from the 18th century7.

In fact, there are good arguments to defend the food-producing nature of Aboriginal society as a whole, as opposed to defining it as hunter-gathering8, even if the discussion is very academic: in the end, pretty much all human hunter-gatherer societies have gone beyond the mere hunter-gathering and have influenced their environments to favor the kind of food production they preferred.

The question probably is one of emphasis on some specific characteristics of aboriginal society9. Those characteristics included, at least by the time Europeans arrived in the continent in the 19th century, a great degree of cannibalism. This would indicate, at the very least, that Aboriginals weren’t so great at producing their own food as sympathetic academics argue10. Were the Aboriginals the world’s most effective cannibals, to the point of keeping their on population at bay through this method? I’m only asking here. Surely, there should be graves with bones showing marks of such custom, and yet I haven’t heard of any such discoveries.

Apart from widespread cannibalism, among the most puzzling Aboriginal social characteristics is regression: it appears clear that some Aboriginal tribes developed agriculture and then forgot it, while others developed boat technology to cross the Torres Strait that was later phased out; there are reports of tribes who had forgotten how to build boomerangs, the most unique piece of technology found in the continent.

These regressions, possibly caused or exacerbated by climate swings, likely contributed to the fact that Aboriginals, when tested, are the human population with the lowest IQ11 and has one of the highest levels of schizophrenia12 – both signs of low levels of cultural capital accumulation. Australia is the only continent in which natives never developed any indigenous pottery13, any sort of even basic urbanization14 or any replicable form of writing, although many Aboriginals used so-called message sticks with various markers to convey messages at some distance, as well as carving on trees often associated with human burials15.

A strong oral tradition developed among Aboriginals which, as all other traditions, is extremely unreliable as any source of historical information and mostly served to provide tribal and ethnic cohesion. Stories about ancient events were referred to as the “Dreamtime” by some historians and anthropologists; even if such stories have no intrinsic reference value, they became the cultural backbone of Aboriginal tribes16.

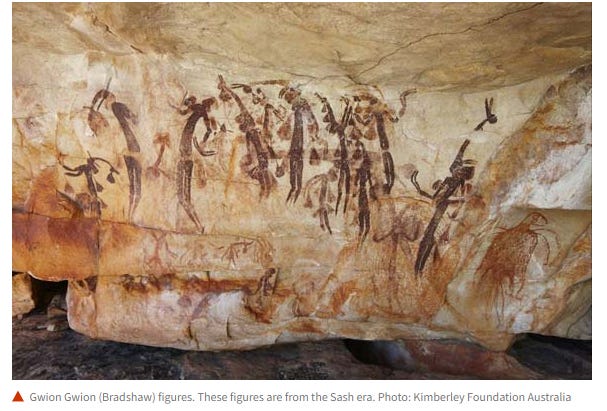

Aboriginal painting on rock walls, most famously in the Kimberley, did reach significant levels of skill. The Gwion Gwion rock paintings, for example, display a level of detail and artistry that is a match for anything seen elsewhere when they were made, around 10,000 BC; and Aboriginal art has been described as the longest unbroken artistic tradition.

Folk art and oral transmission were important backbones of Aboriginal tradition: in the absence of any other points of reference, be they foreign interlopers or mysterious ancient ruins, the Aboriginals were left to themselves to make sense of a strange world. Many of their stories and myths are coherent in a way that ancient peoples from other continents would have understood, but their descendants who actually got to know Aboriginals didn’t: for example, the idea widespread among some tribes that the true father of a child could be a stone, an animal or a spirit, a way to handle complex issues of paternity and paternal authority17.

When European travelers and anthropologists started to study Aboriginal societies in any detail, in the late 19th and early 20th century, these had of course undergone millennia of evolution, often accelerated, truncated or completely derailed by contact with the Europeans, their technologies, products and illnesses.

Still, reports of widespread cannibalism and customs unheard of elsewhere indicate that at least some Aboriginal tribes were rather unlike anything else that developed on Earth. Evidence of extreme violence in inter-tribal clashes and internal vendettas – not unconfirmed by very high levels of aggression and criminality observed in Aboriginal peoples in the 20th and 21st centuries – brings to mind the studies conducted among the Taude of New Guinea, used to endemic warfare and violent conflicts of all kinds18.

The Kurai people of modern Victoria, one of the most fertile corners not just of Australia, but the whole planet, were also extraordinarily violent in their clashes with others. Additionally, they developed a kinship system which classified so many women as one’s “sister” or “mother” that it was virtually impossible for a man to marry without committing incest, thereby quite literally risking death.

This system deserves some explanation: anthropologist Ruth Benedict (in “Patterns of Culture,” 1934) wrote approvingly about a “subterfuge” the Kurnai employed to “avoid extinction.” It seems that young couples could choose to “elope” to a nearby island, and if they succeeded in reaching it without being overtaken and killed by outraged pursuers, they were given sanctuary. If the couple could then manage to survive long enough to bear a child, they were permitted to return to society, but only after running a gauntlet and being pummeled before they were allowed to live as a married couple19.

One wonders: was this kind of maladaptive custom common among Aboriginals? Or maybe they had other, equally picturesque maladaptive customs that I never heard of? I feel like there are tons of things about the original inhabitants of Australia that I don’t know, that perhaps nobody knows, that should be known.

A term that doesn’t include natives of the Torres Strait Islands, in between Australia and New Guinea, who are much closer ethnically and culturally to New Guineans.

Lacking significant glaciers and volcanoes to renew soils, Australia “lays claim in geological terms to be the oldest continent,” as Don Garden writes in “Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific: an Environmental History” (ABC-Clio, 2005). “One penalty paid for that boast is that over millions of years, the leaching effects of rain, wind, heat, and fire have eroded the fertility of the aging soils and flattened the landscape, bequeathing its biota and its later human occupants an essentially flat, worn land and infertile soils.”

Cit. “On Genetic Interests: Family, Ethnicity and Humanity in an Age of Mass Migration,” by Frank Kemp Salter (Routledge, 2006), p. 68.

Garden (Op. Cit.), p. 12.

The estimate is cited in “Australia’s History: Themes and Debates,” ed. by Martin Lyons & Penny Russell (University of New South Wales Press, 2005, p. 14). The number bottomed up at 60,000 by the 1920s.

It was there that European sailors, in this case Dutch, first came to land in Australia, in 1606.

Garden (Op. Cit.), p. 22: “Through their landscape modification and control, Aborigines unconsciously sowed the seeds of their own downfall, assisting the creation of grazing land that was ideal for colonists’ sheep. It is estimated that at the time of European arrival, about 10 percent of the continent was covered by forests and 23 percent by more open woodlands (Beale and Fray 1990, p. 31). The Aborigines had played a part in reducing the tree cover to this level.”

Cit. “Transdisciplinary Approaches to Understanding Past Australian Aboriginal Foodways,” by Michael C. Westaway et al, “Archaeology of Food and Foodways,” 1.11.2023. As the authors put it: “It has long been considered that since Australia’s first colonization… its peoples were supported largely through foraging as opposed to farming. Recent research has challenged that perspective, contentiously proposing that Australia’s first nations peoples developed agricultural systems before European colonisation. This proposal has been subject to significant critique, but support of the food-producing nature of Aboriginal society has been boosted by new multi-disciplinary evidence for early aquaculture and possibly cultivation, as well as for the translocation of plants though trans-continental trade systems. While this analysis has generated new discussion and debate, it has also highlighted systemic empirical biases; archaeological data for pre-European plant exploitation remains sparse, and we consistently rely on potentially unrepresentative and historically shallow ethnographic information to fill that gap.”

This debate was largely triggered by the publication of the book “Dark Emu: Aboriginal Australia and the birth of agriculture” (Scribe US, 2018) by aboriginal historian Bruce Pascoe, since it argued that many pre-colonial Aboriginal groups were farmers, pointing to examples like eel aquaculture in Victoria, and grain planting and threshing of native millet in the arid center. Archaeobotanists Anna Florin and Xavier Carah have observed that food production systems in northern Australia are very similar to those in New Guinea.

It would be very daring to state that Australians of the 1st millennium ate human flesh like their descendants did in the 19th century: what it’s clear is that, as separate observers like P. Foelsche (”Notes on the Aborigines of North Australia”, in Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, vol. 5, 1882) and the missionary Louis Schulze (in “The Aborigines of the Upper and Middle Finke River: Their Habits and Customs”, in Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, vol. 14, 1891) noted, Australian aborigines just before they were absorbed into the Australian state were enthusiastic cannibals who particularly enjoyed killing and eating children as young as two, sometimes their own or members of their own families and tribes, as well as enemy warriors in the American manner – a custom that also appears to have been commonplace, in the 2nd millennium, in Maori New Zealand. Perhaps 30% of Australian aboriginal children were killed and often eaten, particularly illegitimate or deformed children. As William D. Rubinstein wrote in Quadrant (“The Incidence of Cannibalism in Aboriginal Society,” Sep. 25, 2021) “there are literally hundreds of accounts of Aboriginal cannibalism, dating from the first European settlement in Australia to the 1930s or even later. These accounts were made in all the states and territories of Australia with the possible exception of Tasmania. They were written by witnesses and commentators from a wide variety of backgrounds who wrote in many genres—newspaper articles; autobiographies, many not meant for publication; court reports; scholarly proceedings, as in the accounts quoted above. They were written by persons not in contact with one another, often hundreds of kilometres apart, and having no knowledge of the accounts made by other white Australians, and whose veracity, when they wrote on other topics, would not be questioned.”

Cit. “Race Differences in Intelligence: An Evolutionary Analysis,” by Richard Lynn, (Washington Summit Publishers, 2006). In the book they are cited as having an average IQ of 64, compared to about 70-75 for Sub-Saharan Africans. Various other studies have provided similar estimates. See, for example, Michael W. Ross’s paper “Intelligence Testing in Australian Aboriginals,” in Comparative Education, vol. 20, no. 3, 1984.

Cit. “The pattern of psychiatric morbidity in a Victorian urban aboriginal general practice population,” by J. McKendrick et al, Australia & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, March 1992.

They did make baskets, shields and weapons out of wood, bark and leaves, technologies typically associated in Eurasia only with very primitive societies.

The closest thing to a permanent Aboriginal settlement ever found is some clusters of stone houses described as “hamlets” around Lake Condah and Lake Bolac in Victoria, in the southeast. Garden (Op. Cit.), p. 23.

These are called “marara” and are found for example in New South Wales.

See “Indigenous Australian life writing: Tactics and transformations,” by Penny van Toorn, in “Telling Stories: Indigenous history and memory in Australia and New Zealand,” ed. by Bain Attwood & Fiona Magowan (Allen & Unwin, 2001).

As Slavoj Zizek writes in “The Ticklish Subject” (Verso Books, 1997): “In the modern bourgeois nuclear family, the two functions of the father which were previously separated, that is, embodied in different people (the pacifying Ego Ideal, the point of ideal identification, and the ferocious superego, the agent of cruel prohibition; the symbolic function of totem and the horror of taboo), are united in one and the same person. The previous separate personification of the two functions accounts for the apparent stupidity of some aborigines… The aborigines were well aware that the mother was inseminated by the “real” father; they merely separated the real father from its symbolic function.”

The studies were conducted by C. R. Hallpike, who concluded that their practice of warfare was not adaptive. Hallpike also believed that it was maladaptive for the Tauade to raise huge herds of pigs that “devastated” their gardens and led to “innumerable quarrels and even homicides,” only to be slaughtered in such large numbers that they could not be eaten. He also saw no adaptive advantage to the Tauade in keeping rotting corpses in their villages. He observed acerbically, that “No doubt, the Tauade had survived to be studied, but their major institutions and practices seemed to have very little to do with this fact.” Cit. "Sick Societies: Challenging the Myth of Primitive Harmony," by Robert B. Edgerton (Simon & Schuster, 2010).

Edgerton (Op. Cit.) notes that “instead of adhering to her initial view that this extraordinarily cumbersome institution of marriage was a social liability, Benedict chose to see it as a clever social adjustment that permitted people to find a spouse despite violating the Kurnai role against incest.”

There’s some truly fascinating about the low iq and helplessness of Australian aboriginals.

After all, the Australian government didn’t just have to change the entire way gasoline distribution works, because they couldn’t stop themselves from huffing it. In one state, the government basically had to step in, put them all on food stamps and remove most of the children/or put the families under close watch, because of the mass scale of sexual abuse among the aboriginals.

I can’t think of any human population anywhere so unfit for modern life. One gets the feeling, that if the Europeans had never come, there either wouldn’t be any aboriginals in the year 22000, or they’d look and operate in exactly the same way as 25.000 years ago, with zero major changes.

Oops, not good at commenting on my phone.

My father after finishing a fine Art degree in the late 1940's, went 'outback' which is what the inland of Australia is called.

He worked with Aboriginal stockmen driving cattle. Usually family groups still living somewhat traditional lives and he was a marxist, and very curious about their way of life and how they had managed to live without change for so long.

He told me he thought that they had a such a wonderfully satisfying life, so complex, with stories, art, learning how one is related to everything else in the land and every individual is valued from birth to death, the elders passed down the law and everybody obeyed because each child was woven into the fabric of the land through their own creation story and totemic identifiers that were intrically related to the land so the land owned them not the other way around.

There is a lot of literature that is available about all the new knowledge, that is less controversial than Dark Emu but the controversy with this book is political. Conservatives in Australia want people to believe they are stupid and lazy.

The best evidence that they are not stupid is Bennelong. Google Benelong and see how very intelligent he was.

They also are not lazy, or cannibals. I'm surprised people think that. There doesn't seem to be any reference you have listed that provides evidence for this.

Australian anthropologists have done a lot of work that can help you get more info anout these amazing people and their culture.

This reference is good for how they probably came here.

https://set.adelaide.edu.au/news/list/2019/06/26/an-incredible-journey-the-first-people-to-arrive-in-australia-came-in-large