Rome, Year 500

A History of Mankind (321)

To read previous posts in the History of Mankind, which is pretty long, you can click here. Make sure to become a paying subscriber because most are pay-walled.

In the year 500, Theodoric I made his very first visit to Rome. The city, festooned for the event, was in many ways a shocking sight for somebody with a classic education – like the Ostrogothic lord of Italy himself, who would have read about the past greatness of the once, not so long ago, largest metropolis in the world.

The city’s population had declined to likely well below half its peak of about a million, concentrated in the central areas around the old, now crumbling forum dominated by the recently renovated Curia Julia, where the senate still met. Charred houses and gardens growing wild were part of the landscape. Clients and various supplicants congregated in the surviving houses of the nobility, poorer after the loss of rents from overseas estates and yet more influential than ever after decades of government retreat1 that left the aristocrats in command of many power levers.

Entire tracts of countryside surrounding the city, once filled with farms and small houses for immigrants, the poor and marginal populations, had been emptied as whoever survived wars and depredations moved inside the city walls, and found a wide range of vacant apartments to pick from. Many of these migrants congregated outside of churches, instead of noble houses, taking advantage of the Christian vow to help all the poor, and not just the city’s, an expansion of Rome’s ancient tradition.

Rome also presented some familiar sights for those, like Theodoric, who had grown up in Constantinople, surrounded by the fresh, newly-built architectural milestones of Eastern Roman Empire: Esquiline Hill, once the first of the Roman hills to be settled, and the site of Maecenas’ gardens, as well as Nero’s Golden House and Trajan’s Baths, was now dominated by the grandiose Church of Santa Maria Maggiore, built from the 420s. Consecrated in 434, just as Attila became Hunnish king, this was a visible symbol of growing papal power in a city that had been oft-avoided by Ravenna-based rulers.

In the emperor-less city, the senate and the popes had reached understandings and what amounted to a power balance that still didn’t imply anything close to the later dominance of the Christian clergy. As late as 494, Theodoric’s first year as master of Italy, the North African Pope Gelasius I claimed to be outraged that senate members remained supportive of the ancient festival of the Lupercalia, in which every February 14 naked youths dashed through the city whipping ladies suspected of immorality and singing obscene ditties2; Gelasius succeeded in having it banned.

The Colosseum – repaired in 438 after an earthquake – and the Circus Maximus still filled with thousands to see performances (no longer gladiatorial fights or explicitly violent events) and races3. In coincidence with Theodoric’s visit in 500, the Annona subsidy was restored and again distributed among some of the poor in the city, perhaps as many as tens of thousands or even 100,000 recipients altogether; the Stadium of Domitian, the Basilica Aemilia in the Forum, the Temple of Vesta and other public works were refurbished4.

It may have been for Theodoric’s benefit, indeed, that the so-called “Ship of Aeneas,” the hero of the Aeneid and founder of the city, was built by the Tiber and protected by surrounding structure – so that, decades later, the historian Procopius could marvel at the sight of a near-miraculous vessel standing aloof from time itself: “none of its timbers has rotted or gives the least sign of being unsound; intact throughout, as if newly constructed by the hand of its builder – whoever he was – it has retained its strength in a marvelous way up to my own time.”5

A rare sense of optimism is evident among those who witnessed Theodoric’s six-month stay in the city, during which he took up residence in the old, restored imperial complex on the Palatine Hill. Some who live in historical twilights come to believe that a new day is born when night approaches6, and that was certainly the case for a number of contemporary Italians.

After centuries of weak, uselessly scheming or bloodthirsty rulers, these witnesses finally saw a worthy man, young (ish), strong, benevolent and cultivated, in command of a land that once, in not such a distant past, had itself commanded the known world. Many would have been horrified to learn what the future held: that this was the last time in which a grown man would rule all of Italy, for well over 1,300 years.

FROM THE ARCHIVES:

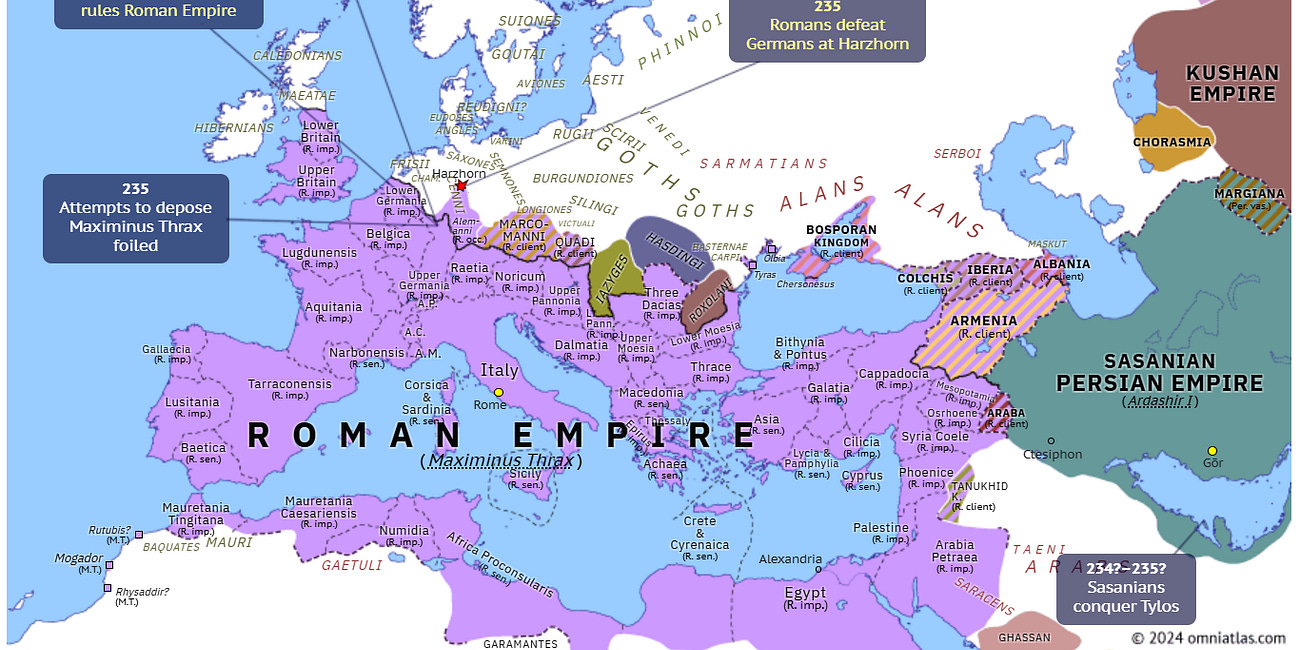

How the Barbarians Took the Fight to the Romans

To read previous newsletters in the History of Mankind, which is pretty long, you can click here. Make sure to become a paying subscriber because most are pay-walled.

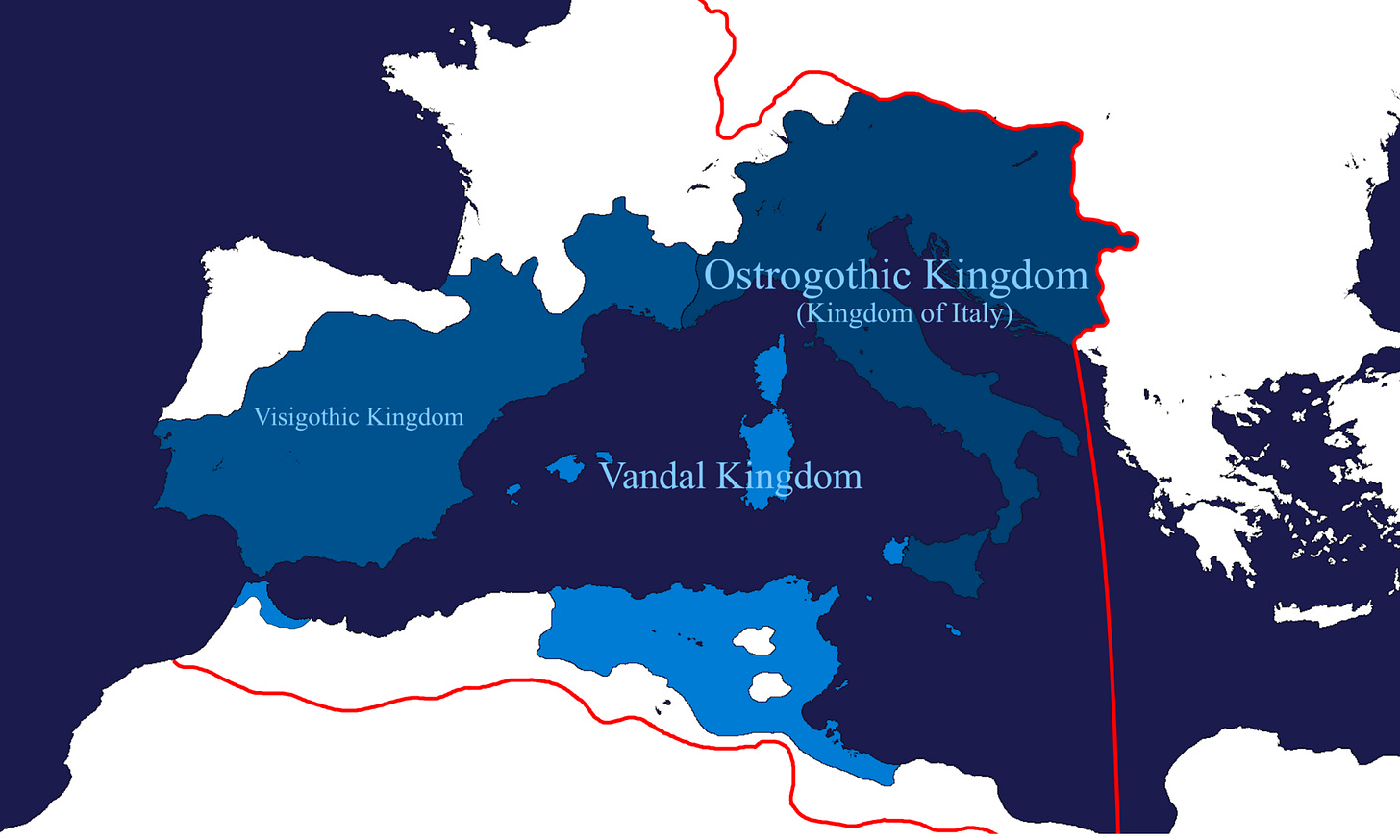

Theodoric, 46 years old as he first visited Rome, expanded his influence in nearby lands through marriage alliances with Vandals, Visigoths, Franks and Burgundians – a policy that wouldn’t have been possible without military successes that made him an ally worth courting. Surrounded by a group of sound, professional generals, over the next two decades he became the most powerful man in the former Roman West.

In 505, Theodoric added Pannonia to his domains, although the region remained mostly under the rule of his vassal warlord Mundo/Mundus7, possibly of part-Hunnish ancestry; two years later, Theodoric became regent for the infant Visigoth king, his grandson Amalaric (born in 502), following the Franks’ victory over Alaric II in the great Battle of Vouillé that ensured Frankish control of most of the land north of the Pyrenees. Alaric was killed in battle by Clovis, the Frankish king, himself.

Almost immediately, cities that had only been under very loose Visigoth control like Marseilles, Avignon and Arles were occupied by garrisons loyal to Theodoric, and thus protected from Frankish and Burgundian incursions; the imperial Prefecture of the Gauls was restored. In an extremely un-barbarian move, Theodoric published a letter to his subjects in Gaul presenting himself as a Roman princeps who had delivered them from barbarian rule, and urging them to recover their Roman customs right down to their togas:

“Roman custom must happily be obeyed by you who have been restored to it after a long time. Recalled to your ancient liberty, cast off barbarism, abandon cruel minds, and clothe yourselves in the morals of the toga. It is not right that you live like foreigners in our just times.”8

During the 510s, Theodoric effectively was ruler of the extensive Visigoth domain in Hispania and a large chunk of southern Gaul, and recognized as such in official documents and inscriptions, through his envoy Theudis, Amalaric’s acting regent. In 511, he proclaimed the first Gallo-Roman consul in more than half a century9.

Theodoric was careful to present himself as a loyal, slightly junior colleague of the Eastern Emperor – this is evident, for example, his preference for the verb “praeregnare” rather than the outright “regnare” to express his powers, especially early on his reign10, and his efforts to end the Acacian Schism dividing the Western and Eastern Churches in 519. Still, such successes fueled Theodoric’s ambition to restore something at least close to the power of the old Western Roman empire.

An imperial attitude is clear, especially late in Theodoric’s reign: whatever his public pronouncements, the Ostrogoth ruler saw the eastern emperor as merely primus inter pares and only one known inscription in Italy refers to both rulers11. His coinage was made in the imperial style and his robes were dyed imperial purple, a color that his predecessor Odoacer had eschewed to avoid Constantinople’s wrath. Like Odoacer, and unlike contemporary barbarian rulers like those of the Franks or Visigoths, Theodoric never styled himself as King of the Ostrogoths; he was merely, in Pyrrhus’ style, the Rex12.

In letters to the senate, Theodoric deplored the theft of decorative bronzes in Rome and the wanton cutting of statues’ limbs in what appear to have been mere acts of hooliganism. And his focus was wide: besides his restorations in Rome, Theodoric also commissioned repairs for multiple public works across Italy, including the Trajan-era aqueduct in Ravenna; new walls and baths at Verona; and a palace, baths, walls and an amphitheater in Pavia. An equestrian statue of Theodoric in Ravenna, later shipped to Aachen by Charlemagne, was wrought of copper or bronze and covered in gold, and may be the last such monument erected in the antique Graeco-Roman style, at least in the West.

This imperial attitude is also echoed, for example, in the language he used to refer to himself – “our lord”, “victorious”, “triumphant”, etc – as well as when writing to other barbarian kings: as he offered two clocks to Gundobad of the Burgundians, himself once a Roman patrician in the distant past, he suggested that these clocks might bring him and his people to civilization; civilized people live ordered lives, and need clocks, Theodoric explained with remarkably pedagogic intent, but “it is the habit of beasts to feel the hours by their bellies’ hunger.”13

In a similar case, when he was looking to procure a cithara and citharist for the Frankish King Clovis, the Ostrogothic Theodoric told his Roman correspondent, the (likely bemused) philosopher Boethius, that he dearly hoped that the musician would “tame the savage hearts of the barbarians with his charming sounds.” But there was no taming the former Roman West.

A fashion developed in this era for attaching long inscriptions to earlier statues of famous pagan ancestors. Peter Brown, Op. Cit.

The Lupercalia persists all over the world in the word “February,” derived from “dies febratus” or “days of purification,” a common name for the festival.

Circuses outside of Rome were kept in good enough state so that Milan’s was still usable for public ceremonies staged by Lombard King Agilulf in the late 6th century. See “Kings of All Italy? Overlooking Political and Cultural Boundaries in Lombard Italy,” by Nicole Lopez-Jantzen, Medieval Perspectives 29, p. 80 (2014).

Arnold, Op. Cit., pp. 222-223. Aqueducts and sewers, neglected for decades, were also repaired across the city. In an Augustan touch, Theodoric had a descendant of Pompey, a senator of the Symmachus family, handle the restoration of the Theater of Pompey – however, Symmachus was given cash from the Theodoric treasury, a sign that even the senatorial elite was no longer to be relied upon for big expenses.

Procopius’ “Gothic Wars.” Nobody else ever wrote about this Ship, which makes it likely that it was an Ostrogoth-era fake.

The sentence is Dávila’s (Op. Cit.), originally in Spanish: “Los que viven en crepúsculos de la historia se figuran que el día nace cuando la noche se aproxima.”

A remarkable, if secondary character of the era, who after Theodoric’s death served the Eastern Roman court with great distinction, in the Balkans, Constantinople and Persia, before he joined the Eastern war against his former Ostrogoth masters, in which he and his son Mauricius were killed.

Variae 3.17.1.

Felix, the son of a learned Gallic senator whose family was said to have suffered great oppression in Gaul. Felix was the first appointee of Theodoric recognized by the East since relations became strained when Theodoric forces took Sirmium from the Gepids in 504 and held it instead of giving it back to the Eastern Romans, so he did his bit to improve relations.

Cit. Jonathan J. Arnold’s “Theoderic and the Roman Imperial Restoration,” (Cambridge UP, 2014) pp. 68-69.

Jonathan J. Arnold, Op. Cit., p. 87.

See “Was ethnicity politicized in the earliest medieval kingdoms?” by Andrew Gillett, in “On barbarian identity: critical approaches to ethnicity in the early Middle Ages,” ed. by Andrew Gillett (Brepols, 2002).

Edward James, Op. Cit.

Thank you. The level of your knowledge is amazing. These centuries of history are all unknown to me.