Welcome! I'm David Roman and this is my History of Mankind newsletter. If you've received it, then you either subscribed or someone kind and decent forwarded it to you.

If you fit into the latter camp and want to subscribe, then you can click on this little button below:

To check all previous newsletters in the History of Mankind, which is pretty long, you can click here.

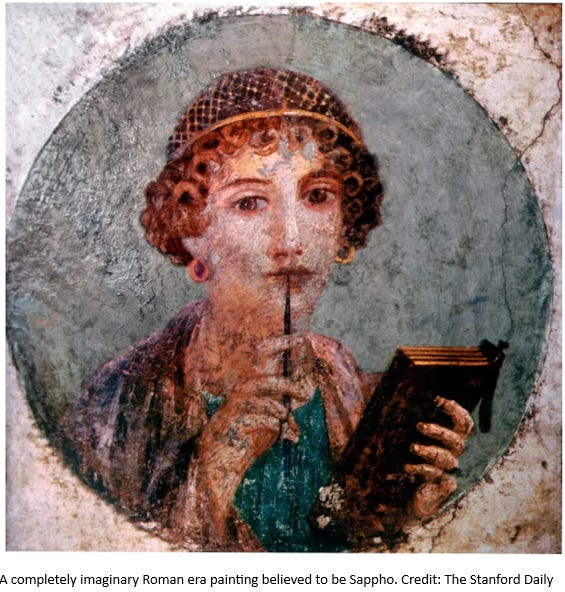

A contemporary of Aesop, Sappho (c. 620-570 BC) took Archilochus’ innovations much further, and her works helped to popularize and sophisticate them.

Like Archilochus an Aegean islander, in her case from Mytilene in Lesbos, she used Homeric metrics to describe non-epic themes and subjects. Few of her poems sum up her approach better than this[1]:

Some think a fleet, a troop of horse

or soldiery the finest sight

in all the world; but I say, what one loves.

A contemporary of the early Neo-Babylonian emperors, who was still alive when the Jews went into the Babylonian exile in 587 BC, the island-dweller Sappho was always a remote and semi-legendary figure for the Greeks who revered her works and memory centuries later[2].

Ovid reports that she ended her life in a suicidal leap for unrequited love of the ferryman Phaon; many others believe she was homosexual (“Lesbian”) and that her writings are full of (somewhat contrived) gay themes[3]; some believe she wrote poems about her daughter, and others see a female lover in that same character.

Again like Archilochus, Sappho came from a wealthy family. Although the resident of a small island, one of her brothers was rich and well-traveled enough to buy himself a prized courtesan from Naucratis in Egypt (as earlier discussed) and she knew her world well enough to write of distant Sardis, capital of the Lydians, with admiration for its architectural beauty and sophistication. Like all Lesbians of her generation, she knew of Terpander’s music and lyrical poetry[4]; in addition, she almost certainly was well acquainted with Alcaeus, a fellow aristocrat and poet also from Mytilene with whom she may have exchanged poems and/or signs of affection[5].

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A History of Mankind to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.