To check all previous newsletters in the History of Mankind, which is pretty long, you can click here.

Xenophon didn’t hate or despise the Persians. In his “Cyropaedia,” a sort of fictional or at least highly creative biography of the founder of the Persian empire that became an archetype for all later “mirror of princes” books in European history, Xenophon uses the example of the long-dead Cyrus the Great to discuss the qualities that make a good king or general, like Cyrus obviously was.

The book is filled with invaluable details about Cyrus’ era. Xenophon describes mock battles set up by Cyrus to train in his army, providing what likely is the longest description of military training routines to be found in any book of the Classical era. The king’s stress on repetition, discipline and officer initiative is much praised by the knowledgeable Greek.

When he has to pick one outstanding quality among the many that Cyrus had, Xenophon chooses this: “He did not run from being defeated into the refuge of not doing that in which he had been defeated.” His point is that Cyrus learned to love the feeling of failure, because failure means you’re facing a worthy challenge1. He also looks at the sort of upbringing, qualities and teaching that produces this character – a theme that connects Xenophon to his philosophical masters Socrates and Plato, and fellow students like Alcibiades: his conclusion is that contemporary Persia, unlike that of Cyrus’ time, is doomed2.

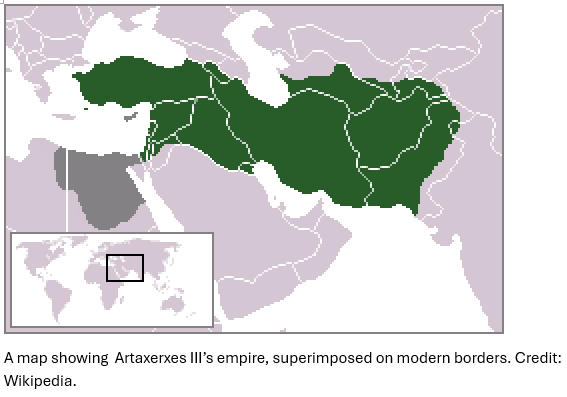

Artaxerxes II, who was smart and resourceful, may have agreed with Xenophon’s low opinion of Persia’s prospects. Left to cause trouble among the Greek powers by supporting one against another, Persia’s strategy sometimes backfired. In 394 BC, he relied on Cyprus Greeks to defeat a Spartan fleet; and this resulted in the elevation of the tyrant/king of Salamis-in-Cyprus, Euagoras, to a position of dominance in the island from which he rebelled, causing much harm to Persian interests in Cilicia and Phoenicia.

Euagoras was eventually contained, first being forced to become a Persian satrap in 376 BC and then murdered in 374 BC. Trouble continued for the Persians: when Artaxerxes II tried to recover control of Egypt in 373 BC, he failed utterly, and his punishment was a decade of civil war as various western satraps rebelled; he was lucky to keep Phoenicia within the imperial fold after the Egyptians, supported by Sparta, resumed their ancient policy of expansion into the Levant.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A History of Mankind to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.