To read previous newsletters in the History of Mankind, which is pretty long, you can click here. Make sure to become a paying subscriber because they are all pay-walled.

The impact of the anti-feminist undercurrent in early Christianity shouldn’t be exaggerated: Rome’s society was actually quite egalitarian when it came to gender by global and even European standards, so the position of women in Christianity to start with was never as low as, say, that of women in Jewish and other traditional Semitic societies. In fact, the first Christian emperor, Constantine, banned sons from disinheriting their mothers.

Roman tradition regarding the female position in society was similar to Sparta’s, so moral examples of stern Roman matrons were oft-cited. Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, was famed for having supported her children, whom she called her jewels, in their perilous fight against patrician privilege. Lucretia had committed suicide, even though both her husband and father had pleaded with her to live, since her rape had not been her fault. When her husband was reluctant to kill himself, as ordered by emperor Claudius, Arria had grabbed his dagger to stab herself, and then told him: “see, it doesn’t hurt.”1

In imperial times, the ancient kind of “manus” (male-dominated) marriage had entirely disappeared and women retained her property and the right to divorce men; men needed approval from their wives to use dotal funds, which is something unheard of anywhere else in the world in this era, and Augustus’ legislation put an end to husbands’ power to kill their wives for adultery, a move perceived as downright shocking in the Semitic (and even Hellenic) East, although perhaps not as much in more enlightened places like Egypt.

This is evident in the “stoning” story related in the Bible, with Jesus appearing as an incredibly daring radical for opposing the public, brutal and collective murder of an adulteress2. As Witzke explained3:

“The law now made it complicated to kill an adulterous woman legally: caught in the act at her father’s or husband’s house, she must be put to death immediately only by her father (not her father- in- law or husband). This father must also be her paterfamilias (a man not under the potestas of another man) and her natural father (not a father by adoption). Her execution could not be put off or take place anywhere else. Furthermore, the adulterer had to be discovered physically penetrating the adulterous daughter, and the pair had to be killed in a single blow. The difficulty in carrying out her punishment effectively eliminated the execution of adulterous women in Rome. In short, Augustus did not wish husbands to kill wives for the crime of adultery as they had been able to do with legal impunity prior to his law. He desired, instead, a public court and public shame, to make a public example of errant women. Augustus’ law took away male private rights over the female body.”

It was also under Augustus when the statue of Marsyas, a mythological figure, in the Roman forum became a symbol of Roman proto-feminism – when his notorious daughter Julia, accused of having sexual dalliances nearby, crowned the statue with flowers4.

An old story about a women rebellion in archaic Rome, cited in Macrobius’ Saturnalia5, would have been just as shocking for many foreigners but it was merely amusing to the Romans: the story is about a young boy named Papirius who had been in the senate with his father; back home, he falsely told his mother, as a joke, that that senate had debated “whether the advantage and interest of the state would be better served by one man having two wives or one woman two husbands.” On hearing this, the mother and other matrons flocked to the senate calling for a law so that one woman could marry two men, rather than the other way around; as Macrobius relates, the senate took the incident well and made young Papirius a permanent member, although it banned the presence of minors accompanying their parents from that point on.

FROM THE ARCHIVES:

The Origins of Rome

Welcome! I'm David Roman and this is my History of Mankind newsletter. If you've received it, then you either subscribed or someone kind and decent forwarded it to you.

Ancient patriarchal customs like the ius osculi – allowing the male relatives of a married woman to check her breath to see if she had violated a ban against drinking alcohol – almost certainly were obsolete early in the republican period. Indeed, they were mocked in the imperial period, for example by Agrippina the Younger when she famously asked her then-husband, emperor Claudius, to kiss her as a drinking test.

Statues depicting real women – as opposed to mythical or literary characters – like the Gracchi’s mother Cornelia and later Augustus’ wife Livia were publicly and prominently displayed in Rome, which wasn’t the case anywhere else at the time outside of Egypt6. Under Roman civil law, women could own property of their own, and those who had given birth to three children were free to manage such property without the intervention of a male tutor by the process known as the ‘‘right of three children.” Female slaves who got involved in a liaison with their owners entered a legal state known as “concubinatus” (concubinage) and were exempted from for work if they had more than three sons with the master7.

Christianity was appealing to Graeco-Roman women, very particularly to upper class women, not because it offered them extra rights, but because it offered them protection from mistreatment and from being discarded – a real risk for them as for every other women on the planet8. Upper class women were especially exposed to the threat of divorce and concubinage because their husbands had the resources to keep mistresses and settle divorces. Upper class Romans frequently complained about nagging wives because, when you can sleep around as much as you want with no social or legal repercussions, paying no alimony and on top of that you have cash to buy beautiful slaves, wives can really appear like unnecessary baggage to your lifestyle.

Wives understood this better than anyone else, as did Christian priests, who recommended that men love their wives with more stress than any pagan priest would have thought advisable. In Ephesians 5, Paul wrote that “husbands ought to love their wives as their own bodies” and remarked that, as far as the husband is concerned, marriage as a bond with the wife outranks attachments to his own family – a profoundly revolutionary idea for any society.

Divorce later disappeared under Christian pressure9, and earlier female rights were retained by Roman women, who in general only saw improvements in their station with the rise of Christianity. In fact, when Constantine strengthened Augustus’ Lex Julia by exchanging the earlier punishments for adultery – fines and banishments – for the death penalty, this only applied to men, which probably caught the attention of the emperor’s Eastern subjects, used to sterner punishments for women than those for men.

In a similar vein, Constantine in 320 decreed that sexual trafficking of minors without their parents’ consent would be punished by death for both the girl and the pimp; but the pimp in addition would have his or her throat and mouth filled with molten lead. Any complicit slaves would be burnt.

All in all, the idea of public morality, involving strict views on homosexual sex and a more constrained social role for women, wasn’t new; in fact, it had been very popular among middle-Republic Romans who were concerned about the influx of decadent Greek ideas of customs, and among Confucian Chinese.

What Christianity did in the West, and Buddhism did in the East, was packaging the idea of morality, as an abstract notion adaptable for each society, as part of a new religious concept that understood personal behavior as something that contributed more to personal salvation than sacrifices and worship, for millennia seen as the main requirements for religious practice. Paul’s coinage (or at least frequent use) of the Greek term “porneia” (meaning illicit sexual activity, from which pornography is derived), one much repeated by later Christian moralists, indicates that a degree of morality was to be expected from all, women as well as men. As Louise Perry wrote:

“Modern feminism is not an enemy of Christianity; it is its descendent. The moral ideas that form the basis of feminism are derived from Christian values that are, in historical terms, highly unusual: respect for women and the protection of the vulnerable may seem to us to be universal virtues, but they are not.”10.

This was a similar process, conducted over a similar timeline, with similar results across the Christian and Buddhist areas of influence, albeit not exactly the same: at the household level, Buddhism did not have anywhere near the sort of impact on China that Christianity had in the West. In Europe, Christianity led to the end of the Roman ancestral cult; in China Buddhism co-existed with the ancestral cult. In the West, concubinage became unacceptable in public with Christianity; in China, sexual mores were unaffected by Buddhism. In the West, Christianity elevated celibacy, even for non-clerics, as something virtuous by itself; in China Buddhism did not make it easier for women to reject marriage, unless they became nuns11.

Earlier religions such as the Greek, Egyptian or Mesopotamian cults, even to a large extent Chinese Taoism, were based on rituals to flighty gods and specific, often short-term rewards that were expected from them if the proper procedure was followed. The turn towards morality, and an associated focus on self-discipline and asceticism, may have been due to growing personal wealth, a consequence of technological improvements across the somewhat-pacified and somewhat-unified lands of the Mediterranean, India and China, that led to cultural switches toward what later was called “delayed gratification”: the promise that, by giving up some of the presently available material benefits, loftier long-term goals can be prioritized12.

In the end, the values fostered by affluence, such as self-discipline and short-term sacrifice, are exactly the ones promoted by moralizing religions, which emphasize selflessness and compassion. These religions first spread among the common people in search of consolation and hope for the afterlife, but eventually got the attention of the upper classes who had their worldly needs attended to. In such circumstances, their focus shifted away from material rewards in the present and toward spiritual rewards; in societies where the well-off had a reasonable expectation of living a long, comfortable life, moralizing religions helped to reflect new values13.

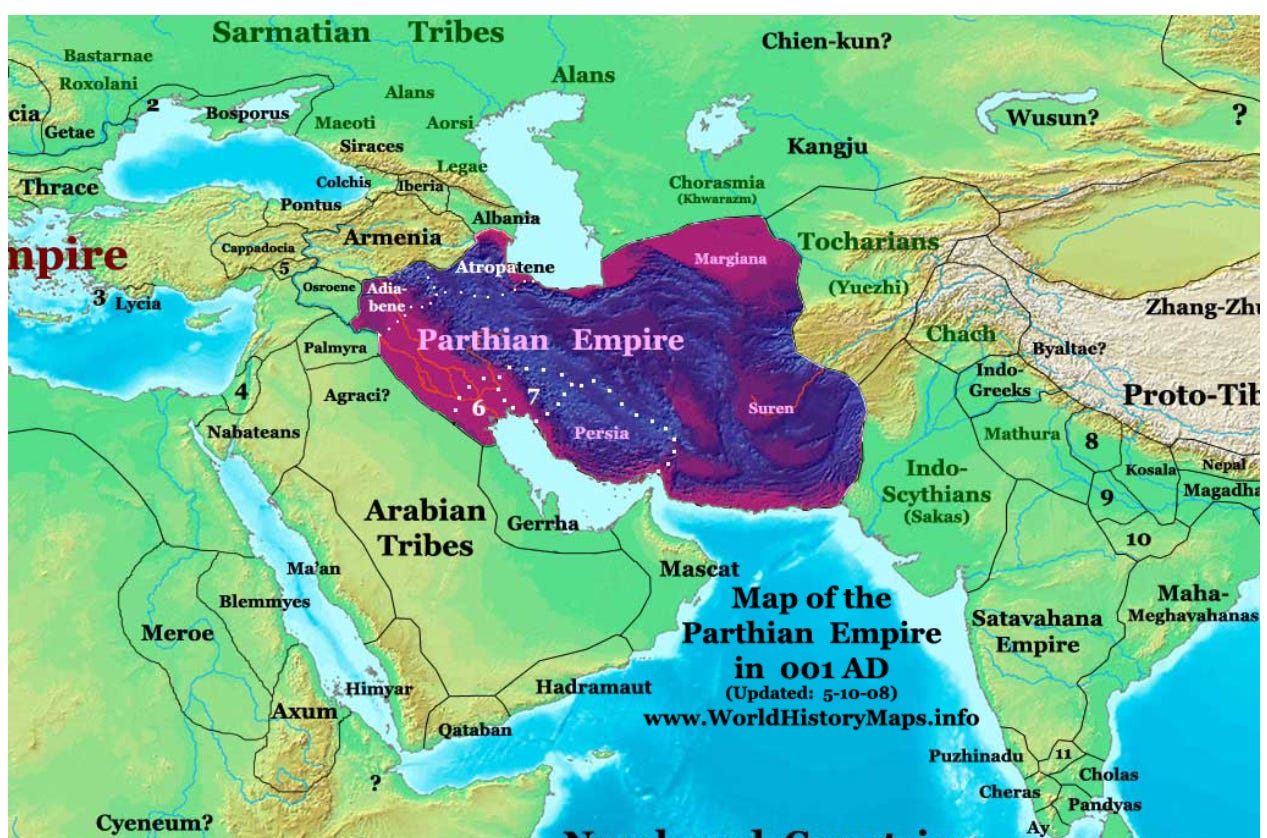

Mediterranean market demand may be said to have found an appropriate supplier of moralizing religion in one of several Jewish schisms, while Eastern demand was eventually satiated by Buddhism as transmitted via the Kushan Empire. In Parthian Iran, monotheistic for longer than any other region in the world perhaps including Palestine, the picture was more complex.

Vologases I (51-78 AD), the son of a Median prince by a Greek concubine, inherited the Parthian throne from his father, an usurper who died a few months into his reign, with dreams of decisive victories against Rome. Decades of Roman intrusions, attacks and long conflicts over the control of Armenia had led to multiple Parthian kings succeeding and fighting each other, often with Roman financing and support, while the Parthian realm was unable to secure its eastern borders with the Kushan Empire and struggled to maintain its multi-ethnic populations under control.

After an early display of strength in 53, the Parthians imposed their own candidate on the all-important Armenian throne, but the arrival of Nero’s general Corbulo complicated matters, which led to a long and indecisive war that only ended with Parthia accepting the Roman candidate to become Armenian king, to great fanfare, in 63.

Peace with Rome afterwards was long-lasting to the point that Vologases went as far as offering Parthian troops to help quell the Great Jewish Revolt from 66. The second half of Vologases’ reign was only disturbed by a series of destructive raids by Alani14 horsemen along the northern parts of his empire, against which Vologases requested, and did not receive, Roman help; this left the king focused on administrative problems and his own religious concerns, with highly significant effects.

Vologases, a man drawn to spiritual concerns, appears to have kickstarted a transition away from primitive Mazda-based Zoroastrianism into the better-defined religion later dominant across Iran up to the Muslim invasion in the 7th century. Later Zoroastrian texts state that it was a king of that name15 who asked Magian priests to bring together all the oral and written traditions of their religion and record them systematically, beginning the process that, centuries later, led to the assembly of the texts of the Avesta and the other holy scriptures of Zoroastrianism.

Such a move would fit with Vologases’ other decisions and concerns, focused on stressing the Iranian character of the Parthian state, one that in his era retained significant Hellenic characteristics. He’s said to have built a new capital named after himself near Seleucia and Ctesiphon, with the aim of avoiding places that were perceived as insufficiently Iranian, being inhabited by local Semites, Greeks and diaspora Jews. He was also the first Parthian ruler to have the Parthian Persian script appear on his minted coins next to Greek inscriptions16.

Whatever the impact of Vologases’ reforms, the 2nd century saw the spread of Zurvanism, the old and firmly monotheistic branch of Zoroastrianism that taught the supremacy of creator god Zurvan, just as Christian teachings started to trickle out into the Parthian realm. This branch was solidly established across the empire by the time Sasanian dynasty provided Zurvanism with royal patronage in the 3rd century, and had a significant influence on Iranian prophet Mani, born in Mesopotamia around that time.

The story is in Pliny the Younger’s letters.

Bauman (Op. Cit., p 33) notes that Roman law before Augustus also allowed fathers of unfaithful women to kill their lovers, but only as long as they also killed their own daughters too.

Op. Cit.

The story is in Pliny, who uses it to exemplify Julia’s “shamelessness,” however.

Book 1, Chapter 6.

Cit. “Women and Gender in the Forum Romanum,” by Mary T. Boatwright, in “Transactions of the American Philological Association 121 (2011), pp. 105-141. A bronze statue of Cleopatra VII was kept inside the Temple of Venus Genetrix in Rome, as the first example of a living person having a statue placed next to that of a deity in a Roman temple, at least until the 3rd century AD. For decades and perhaps centuries after her death, Alexandria was filled with artwork depicting Cleopatra VII.

Cit. Columella’s “Re Rustica,” 1.8.19.

A remarkable number of women not directly associated with Christ appear in the New Testament as early converts, including Phobe, Junia and Priscilla, as well as Euodia and Syntyche, ministers in the early church cited by Paul in his letter to the Philippians. The first Christian convert in Macedonia had been a woman in Philippi, the wealthy Lydia (see Acts 16:13-15, 40).

The root of Christian hostility to divorce is in Matthew 19. There, Jesus is asked by some pharisees whether Moses was wrong to allow divorce, and Jesus responds that divorce is always wrong, although exceptions were made in the past because people was not yet ready to accept all of God’s commandments. Jesus also adds a crucial remark, later used to justify the annulment of some marriages: “I tell you that anyone who divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, and marries another woman commits adultery.” Constantine made unilateral divorce harder to obtain, especially for women, even as he removed the Augustan penalties on the unmarried, possibly to favor Christian monasticism. During the two centuries from Constantine to Justinian I, several emperors successively restricted the practice. Justinian was the first to ban it altogether, temporarily.

In “The Case Against the Sexual Revolution” (Polity, 2022).

See Ebrey, “Women and Family…”

That the shifts towards morality was fairly well synchronized around Eurasia is a fact first noted by Nicolas Baumard, a psychologist at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. His insight was based on the previous work of German philosopher Karl Jaspers, who dubbed the time when these new religions arose “the Axial age.” Jaspers' reputation has had his up and downs, but the expression has more or less survived among experts, at least in English and German. It helps to show how the groundwork was laid for the later success of Christianism and Islam. The theory of affluence, to explain why this was the case, why in this era and not before or later, is also Baumard’s.

According to a 2014 article in New Science magazine, Baumard went as far as gathering historical and archaeological data on many different societies across Eurasia in the Axial Age and tracked when and where various moralizing religions emerged. He found that “one of the best predictors of the emergence of a moralizing religion was a measure of affluence known as 'energy capture,' or the amount of calories available as food, fuel, and resources per day to each person in a given society. In cultures where people had access to fewer than 20,000 kilocalories a day, moralizing religions almost never emerged. But when societies crossed that 20,000 kilocalorie threshold, moralizing religions became much more likely.” The article quotes Naumard as saying: “You need to have more in order to be able to want to have less.”

Alans or Alani appears to have been a catch-all term to describe Iranian (Aryan) raiders originally from the eastern steppes, often with a significant western steppe component, to the point that Romans in the 5th and 6th centuries AD, including Procopius, considered them a type of Goths rather than Eastern peoples.

“Valkash” in Persian. There were other Vologases/Valkash, and none stands out as a good candidate for religious reformer. Vologases II was a son of the first who fought a civil war against his brother, heir Pacorus II, and was executed in 80; Vologases III (r. 110-147), a grandson of the first, fought Trajan for control of Mesopotamia during a very long reign also characterized by warfare against usurpers, Alani hordes and the Kushans; the also long-lived Vologases IV (r. 147-191) also engaged in numerous campaigns against the Romans, with suboptimal results, and in any case his reign is probably too late to correspond with any reforms that should have long been in place by the 3rd century.

Axworthy, Op. Cit.

Some religions are more 'moral' than others. Of course, that depends on one's definition of moral.

Rise of moral religions in the 6th century is bound up with the rise in self-consciousness from the earlier bicameral mentality as posited by Julian Jaynes.