Quick Take: Sparta, Definitely, Absolutely 100% Not a Fascist State

It's worth reminding people that liberty comes in many shapes and forms

Too many people of the 21st century are obsessed with finding historical comparisons with the political disputes in the 20th century between Fascism, Communism and democratic states. Somehow, these anachronistic urges often lead people to conclude that Sparta, the most freedom-loving polis in the history of ancient Greece, was a sort of proto-Fascist state.

Such accusations are easy to find: last year in Foreign Policy, a magazine oriented to Blob policy types lurking in my own, beloved Washington DC; not long ago in the New Republic, for a long time one of the best American magazines; in high-level seminars; even made in social media by the great

.If you know your Fascist states, you know that their defining characteristics are single-party rule, nationalism, anti-feminism (women are expected to take a place as mothers and wives only, as a rule) and government control of the economy in partnership with the private sector.

Many characteristics that some people believe are typical of Fascist states were only typical of some, like Nazi Germany (for example, racism, which was absent in, for example, Franco’s Spain and other European Fascist nations) and not at all exclusive of some Fascist states: the US in the 1930s, with its Jim Crow system, was arguably more racist than any Fascist state on the planet; the democratic British Empire, with its white rule arrangements in places like India and South Africa, was vastly more racist than any Fascist state of the 1930s as well.

Some people also think Fascist states were “totalitarian” in economic terms, which is wrong inasmuch as the private sector blossomed in every Fascist state, unlike the case in other “totalitarian” nations of a Communist bent, all of which put the whole economy under state control and banned almost all private property. Fascist states did exercise a degree of control over the private sector, but definitely didn’t crush it at all.

Now that we set the terms of the discussion for what Fascism is, it becomes pretty clear that Sparta was not a Fascist state or a proto-Fascist state in any meaningful sense of the term. It was definitely sort of racist or at least segregationist (LIKE EVERY OTHER STATE ON THE PLANET AT THE TIME) in that the population was divided by ethnic groups with different status and rights, same as in Athens and in Rome — which was actually more racist that Sparta and any Greek polis, since it only gave citizenship to those born of two, rather than one, citizen.

Then again, we just stated that racism wasn’t a defining or unique characteristic of Fascist states so, moving on.

Sparta hated, hated private enterprise with a passion. Money and commerce were banned for Spartan citizens, who had to live in communal arrangements with very limited private property of their own. We just stated that this is THE OPPOSITE of the Fascist attitude towards private enterprise so, moving on.

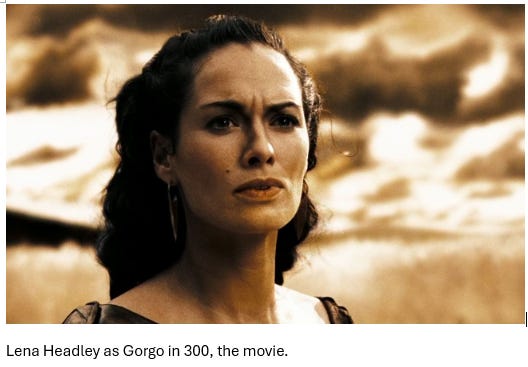

Sparta was the most feminist of all Greek poleis. Many of the best-known women in ancient Greek history were Spartans, including — as the legend goes — the headstrong Helen of Troy. Gorgo, wife of King Leonidas, who would die in the Battle of Thermopylae in the 5th century BC, was once asked why they were able to rule men, where elsewhere in Greece women could not, and she replied that this was “because we are the only ones who give birth to men.”

While Spartan males were out in campaign, they left the management of much of the city on women’s hands. This is an early characteristic of Spartan statehood, following the Messenian conquest in the 8th century BC: after that campaign, Sparta’s laws were amended to limit the power of kings by increasing that of magistrates called “ephors,” who were given the right to try kings and remain seated in their presence (yeah, I know, typical Fascist behavior, right?) and laws were also tweaked to improve both the incentive and the ability of women to manage agricultural land, by boosting women rights1.

From that point, Spartan women were allowed to inherit and bequeath land, a practice rarely found in mainland Greece. Sparta also implemented universal education for girls and granted women complete freedom of movement, both steps unprecedented in ancient Greece. In addition, Sparta’s laws and social norms discouraged Spartan women from engaging in the type of household activities that occupied the time of women elsewhere – a custom made easier by the availability of serfs around.

Sparta’s feminism stands in stark contrast with the female condition elsewhere in Greece and was frequently remarked upon. It’s not really clear whether how often Spartan women used the veil, defined as any garment that covers the head or the face, a tool to promote female public invisibility and silence elsewhere in Greece – since Spartan women weren’t commonly described as invisible or silent.

Women in Sparta were also, unlike most in Greece, very much into sports. Spartans, being superbly fit, were of course pretty dominant in the Olympic Games and in fact kept a pretty glorious string of wins in Olympic chariot competitions between 449 BC and 420 BC — a string broken only because Athens and its democratic allies were, like modern democracies, prone to banning rivals from competitions such as the Olympics, and Sparta was indeed banned from the games. Sparta returned to the Olympics in 396 BC with a freaking, female bang.

That year, Sparta’s next chariot victory became famous because it was won by Kyniska, daughter of King Archidamos. As a woman she could not attend the Olympics, but she entered a four-horse chariot owned by her and still became the first female Olympic victor. Kyniska won another Olympic victory in the four-horse chariot race in 392 BC; and two monuments at Olympia, uniquely gender-egalitarian in machoist Greece, celebrated her success2.

Sparta was, by contemporary standards and even those of much of the contemporary world, so strongly feminist that the role of women in Sparta reverted to the Greek norm after the city lost its independence. It was so feminist that, as several authors have argued, feminism may also have made the eventual loss of Messenia – and thus the demise of women’s rights – inevitable, as Spartan women started having fewer children because they had other duties, and this led to a collapse in the number of male Spartan citizens, those who manned the army protecting Spartan women’s rights.

After Sparta enacted its 8th century BC reforms, its population immediately began to decline. By the early 4th century BC, it was one-fifth of what it had been 200 years previously (in 371 BC, Sparta had only just over 1,000 adult male citizens), according to Paul Cartledge’s estimates in his “The Spartans: An Epic History” (2002), so the Spartan army no longer had the manpower necessary to maintain its position as the preeminent Greek military power, and Sparta lost its conquered land, the raison d’etre for women’s rights.

This is not an unlikely theory: Aristotle, a contemporary, thought that “olinganthropia,” shortage of military-age men, was the cause of the Spartan demise. If nothing of this sounds like anything even very, very remotely approaching Fascism, well, it is because it wasn’t so. Moving on.

Sparta was also widely known across Greece as freedom-loving, hardly the most obvious description of a Fascist state that springs to mind. The Spartans had no slavery or slave-trade (unlike pretty much everyone else at the time) although they occasionally kept prisoners of war as slaves to work next to serfs.

As a rule, most Spartans didn't see these strict customs as inferior to those of other Greeks, and many Greeks agreed with their view. In fact, in antiquity many thought the Spartan system made for freer citizens, an opinion transmitted by Plutarch, who believed that Spartan free men were freest in the world, never subject to either the manipulations of demagogues, as prominent and not-so-prominent Athenians were, or the unflinching diktat of the absolute king3.

Among the Spartans, the opinion was widespread that they fought to maintain their old way of life, which was good enough for their ancestors, so it was for themselves, regardless of what other Greeks thought. Many concurred throughout antiquity: Brutus, who was to kill Caesar in the First Century BC to try and save the Roman republic, admired the freedom-loving Spartans so much that he named parts of his estate at Lanuvium after famous Spartan landmarks.

In a story told approvingly by Seneca4, a captured Spartan who became a slave of his captors kept shouting “I will not serve” in his own Doric dialect. As soon as he was ordered to carry out a basic and insulting service – he was ordered to empty a chamber pot – he bashed his own head against a wall. No such story would ever be told about an Athenian, and none indeed ever was.

Sparta wasn't all about relentless violence, as it preserved its regional dominance more by restrained threat than by aggression and hunger for conquest. Thucydides, a client and supporter of Pericles who was not their friend, portrays the Spartans as reluctant to go to war and often more merciful than their supposedly more humanitarian opponents, the Athenians. It’s significant that, when Sparta won the bloody Peloponnesian War, generally speaking it spared a defeated Athens from the violent reprisals that Athens itself often meted out to defeated cities.

Spartans were true freedom-fighters, not in the figurative sense, because they hated tyranny. The only reason why many Greek poleis instituted democracies (INCLUDING ATHENS) was because Sparta conducted military interventions against tyrants. Athens, and its subject poleis, soon returned the favor by launching the Peloponnesian War, which they fought to the bitter end. After Athens, defeated, reneged on its terms of surrender, Sparta — uninterested in forever wars — let them be.

Let’s agree that nothing here sounds like Fascism either.

Spartans, by the way, were — unlike most other Greek poleis — pretty opposed to pederasty. This may be neither here nor there regarding the discussion of whether Sparta was Fascist, but I think it’s important to point this out because Spartans — again, unlike most other Greeks — thought that subjecting minors below the consent age to sexual relations with their elders was wrong and an attack on such minors’ liberty. Just leaving this out there.

I would like to close my argumentation with one final point regarding the latest in the Sparta-is-Fascist articles, that written by the classicist Bret Deveraux, whose scholarship I very much admire.

In the Foreign Policy article I referred to earlier in this post, Deveraux argues against giving the idea of military virtue, as exemplified by the Spartans, too much importance: not because he’s a pacifist (on the contrary, he’s a nuclear-weapons-loving interventionist) but because, when he writes on Foreign Policy, he knows he’s got the ear of the DC foreign policy establishment and he wants to tell them how to do imperialism right.

Deveraux mostly focused on the idea that the Spartans — the legendary warriors who won the Battle of Plataea against the Persians, the ones who liberated Athens and then crushed it when the Athenians turned against them — were overrated soldiers:

Sparta’s military mediocrity seems inexplicable given the city-state’s popular reputation as a highly militarized society, but modern scholarship has shown that this, too, is mostly a mirage. The agoge, Sparta’s rearing system for citizen boys, frequently represented in popular culture as akin to an intense military bootcamp, in fact included no arms training or military drills and was primarily designed to instill obedience and conformity rather than skill at arms or tactics. In order to instill that obedience, the older boys were encouraged to police the younger boys with violence, with the result that even in adulthood Spartan citizens were liable to settle disputes with their fists, a tendency that predictably made them poor diplomats.

The problem with his argument is not so much that is demonstrably false (he does have a point, however, in that Sparta, like every other military power ever, sometimes lost battles and wars, which reminds me of the famous Roger Federer speech about all the games he lost in his unmatched tennis career). The problem is that, like the “proto-Fascism” accusations, it’s similarly driven by contemporary concerns and seeks to detach the Spartan militaristic ideal from our modern ideals: he wants to give DC good counsel, and he’s alleging that the Spartans are the wrong blueprint because they never built an enduring empire.

I know some people in DC appreciate the point. After all, forever wars are profitable for many in DC. And I myself published a whole freaking book about ancient people who wanted to make a living advising important people! The problem is that Sparta never built an empire because it never meant or wanted to be an empire, so criticizing Sparta because they never accomplished what they never intended to accomplish is unfair.

Western scholarship is obsessed with the question of what exactly made the Roman Empire fall, but the protracted fall of Sparta (the city would remain largely independent, and often bellicose, until the Second century BC), is a much more interesting issue. As Paul Cartledge noted, most historiography which deals with the period between 404 and 362 BC is concerned to pin down where Sparta went wrong “with the benefit of hindsight,” attempting to isolate those factors “but for which [Sparta’s loss of hegemony] would either not have occurred in the form it in fact took or not have been resolved in the way it in fact was.” This is in many ways the wrong question.

The Spartan system was an excellent defensive system, ill equipped to administer an empire, and there were no provisions, such as a hereditary priestly class, that would have allowed it to survive a military conquest – a contingency that was all but inevitable in the ancient world and even today.

Polybius, a Hellenistic historian who documented the rise of Rome, gave a balanced summary of the greatness and limits of Sparta through a useful comparison with the Roman Republic. He remarked that “the constitution so framed by Lycurgus preserved independence in Sparta longer than anywhere else in recorded history” (Polybius, 6.10). Furthermore:

“The Lycurgan system is designed for the secure maintenance of the status quo and the preservation of autonomy. Those who believe that this is what a state is for must agree that there is not and never has been a better system or constitution than that of the Spartans. But if one has greater ambitions that that – if one thinks that it is a finer and nobler thing to be a world-class leader, with an extensive dominion and empire, the center and focal point of everyone’s world – then one must admit that the Spartan constitution is deficient and the Roman constitution is superior and more dynamic.” (Polybius, 6.50)

As Helen Roche argued5, after two centuries of dominance in Greece, the adjustments needed to transition to Mediterranean empire “might very well have seemed both impractical and unnecessary to contemporary Spartans.” Obviously, if the DC foreign policy establishment is in the business of building an empire, they shouldn’t do as the Spartans did.

My point is that just don’t need to underrate Sparta’s accomplishments, to misinterpret historiography and make use of the Elevatio ad Hitlerum argument to make that case. And, also, let me go back to the beginning: this Spartan focus on their own concerns, this unwillingness to mess with others and to build gigantic empires, does it sound Fascistic to you?

For details on this little-known issue, I recommend the 2007 paper “Rulers Ruled By Women. An Economic Analysis of the Rise and Fall of Women’s Rights in Ancient Sparta,” by Robert K. Fleck and F. Andrew Hanssen.

See Donald G. Kyle’s “Greek female sport: rites, running and racing” in “A Companion to Sport and spectacle in Greek and Roman antiquity,” ed. by Paul Christensen and Donald G. Kyle. Wiley & Blackwell (2014), p. 267.

Benjamin Constant, a Swiss-French liberal thinker writing in the 19th century, argued that there are two kinds of freedom: one ancient, one modern. Modern freedom puts a premium on rights – that is, assurances that people would not be prevented from acquiring property and using it as they wished (Constant also included freedom of expression and association here, but no modern state fully guaranteed this, ever). It entails putting limits on politics that would restrain both tyrants and tyrannical majorities a la Athens. Ancient liberty, on the other hand, is majoritarian. It's not individual but communal. To be free in an ancient sense is to participate in the life of the city on equal terms with others, and have a say in public debates on domestic and foreign affairs, the results of which would bind everyone. This Spartan kind of freedom is active, not passive. It has no concept of a private sphere of rights—but it's freedom nonetheless. Constant claimed that this communal form of freedom is disagreeable for modern liberals, who demand different things from their governments, and crave the luxury that only individual freedom to engage in commerce can provide. The French Revolution, he claimed, was nothing more than a misguided effort to force this austere ancient form of communal liberty on a modern people accustomed to nice things.

Moral Epistle 77.14-15.

In "Spartan Supremacy: A "Possession for Ever"? Early fourth-century expectations of enduring ascendancy," (in "Hindsight in Greek and Roman History," ed. Anton Powell, Classical Press of Wales, 2013, pp. 91-112)

Saying that Spartans has no slaves because you call Helots ‘serfs’ instead is misleading. A society where a small warrior elite oppresses a massive unfree class of people is not ‘freedom loving’.

“The Tragedy of The Neocons is they wanted an Empire, but they wanted to commute to work.”

- myself, a humble soldier.

“the ear of the DC foreign policy establishment and he wants to tell them how to do imperialism right.” But They have no ears, they want an app for Empire.

Many in DC make a good living off Forever Wars.

Yes, we noticed.

We noticed a great many things.